Continuing in our search for the Greatest Welsh Novel, Jim Morphy extols the virtues of The Life of Rebecca Jones by Angharad Price (Translated by Lloyd Jones).

My nomination for the Greatest Welsh Novel is a book I haven’t read: O! Tyn y Gorchudd, by Angharad Price.

To be decent, I’ll pick it alongside one I have: its magnificent English-language version, The Life of Rebecca Jones, expertly translated from the Welsh by Lloyd Jones.

However, even taking into account the quality of Jones’s transfer, I know I’m missing out by being unable to read the book in my country’s language.

However, even taking into account the quality of Jones’s transfer, I know I’m missing out by being unable to read the book in my country’s language.

As Jones himself has said: ‘No translation can truly capture the original, especially a book which is so quintessentially Welsh as O! Tyn y Gorchudd.’

Quintessentially Welsh. Jones’s phrase gets to the heart of why The Life of Rebecca Jones gets my choice as the Greatest Welsh Novel and why reading it gives my monoglot self pangs of regret.

The Life of Rebecca Jones is an undeniably brilliant book. Even if, for a moment, we take out that murky middle word, Welsh, and all the considerations that go with it, it would still get my vote as the greatest novel on our list of 25.

It’s an ingenious blend of fact and fiction, with our storyteller Rebecca (a member of Price’s own real-life family) looking back on her life in the rural community of Maesglasau, mid-Wales, from the start to the end of the twentieth century. Price gives Rebecca a dignified voice and a deeply moving story to tell.

In particular, we read the true tales of Rebecca’s brothers, three of who are blind and have the opportunity to be educated and find work away from the valley. A fourth brother yearns to be a doctor and travel the world, but is bound to the family farm. Maesglasau itself – with the evocative descriptions of the hills, the farms, the crag, the ruins, the mountain stream – is a character as much as any person in the book.

Rebecca’s own love story is gently-placed, almost half-hidden, into the book’s pages. And, of course, the novel’s final paragraph is as heartbreaking as any paragraph you’ll find in world literature. It’s an ending that shows what a loving book this is.

The Life of Rebecca Jones is a quiet novel, written in a style that is both straightforward and spell-binding.

Added to all this – and added to our competition – is the idea of Wales.

The Life of Rebecca Jones is soaked through with a certain Welshness. It consumes you with a sense of place – with a history, a character, a language, a way of life. Price deftly uses Rebecca’s intimate tale to capture the much bigger stories of a Wales. Read the 150 uncluttered pages of The Life of Rebecca Jones to discover an entire culture. This is, for me, what makes The Life of Rebecca Jones the novel of our nation.

Rebecca recalls her ‘Welsh chapel childhood’. We see the grace and dignity of her mother, who lived by the motto ‘believe in God and do your work.’ We see the farming community living and working together, their rhythm dictated to by the seasons.

Spinning out from this personal narrative are the grander stories passed down through the generations. We read of Olwen from the Mabinogion ‘who leaves white traces’. Of Cadair Idris, to the summit of which Rebecca never ventured as ‘it was said you’d come down mad – or a poet’. Of the Red Bandits of Dugoed who robbed their victims without mercy. Of Hugh Jones’s wondrous writings.

The Life of Rebecca Jones creates and carries this weight of history with an effortless ease. Price crafts together the personal and the mythical with not a join in sight.

This is not to say The Life of Rebecca Jones is a simple celebration of a single and pure heritage. Far from it. This is more a story about the tensions that come from a traditional way of life.

As Rebecca herself says when looking back: ‘I felt forces in my womb pulling me this way and that. Whether to embrace my ancestors’ traditions, or reject them?’

She rails against ‘This detestable tradition of woman as maidservant!’. She has regrets over her father’s farming life, where there ‘wasn’t the time to indulge in fatherhood.’ Rebecca raised a personal ‘temple to tranquillity’ in the valley – this brought her the peace she sought, but it also brought her loneliness. Her brother Lewis is torn between his non-conformist upbringing and his yearning for the unshakeable dogma of Catholicism. Brothers Bob and Gruff: ‘one a Labourite and the other a Tory. One was a Union man and the other an Establishment man. One a Welsh Congregationalist and the other an Anglican.’

These tensions go for society too. The Life of Rebecca Jones paints an often, but not wholly, wistful picture of a changing valley, a changing Wales, a changing world. New technologies, new ideas, new people make their way into Maesglasau. Modernity encroaches. As does, of course, the English language.

In particular with this respect, we read of the brothers’ schooling: ‘Gruffydd and William’s journey towards education would be irreversible, taking them away from the Welsh language and its culture to another language and culture; away from Wales to another country’. The reader is always aware of Rebecca weighing up the pushes and pulls of ‘progress’ and ‘tradition’.

Towards the end of the book, Rebecca and her family watch a TV documentary that’s been made about the ‘three blind brothers from Tynybraich’. Rebecca weeps at what she sees: ‘The greatest pain was the lie perpetrated by the film. It seemed to say nothing changed, yet clearly showed that nothing lasted.’

In many ways, this lie helps explain both the novel and the Welsh (or any) identity. Things change; things stay the same. We search for a rootedness as time marches on. As Rebecca says: ‘A longing for continuance lies at the heart of our nature, and we lie at the centre of those forces which pull us this way and that like some torturer.’

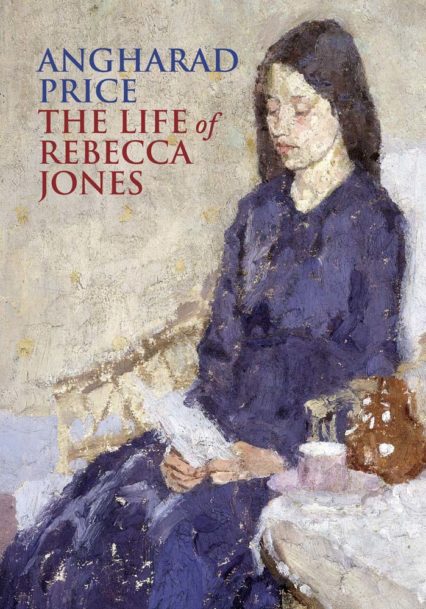

The Life of Rebecca Jones is a stunning essay on a shifting Wales and a shifting Welshness. The Life of Rebecca Jones is a wonderful tribute to a great woman, her family and the glorious valley of Maesglasau. The Life of Rebecca Jones also has one of Wales’s greatest paintings as its front-cover (but we’ll save that chat for another day).

To my jealous eyes, O! Tyn y Gorchudd alone seems the Greatest Welsh Novel. Its language gives it an added Welshness that The Life of Rebecca Jones simply can’t match. And that I can’t match either. Reading The Life of Rebecca Jones makes me feel more and less Welsh at the same time. In exploring its own tensions, this book, more than any other, gets to the heart of my own identity.

So – not least to give credit to the superb author and translator Lloyd Jones – I’ll happily package the English and Welsh versions together:

My vote for the Greatest Welsh Novel goes to O! Tyn y Gorchudd and The Life of Rebecca Jones. I hope your vote does too.

This piece is a part of Wales Arts Review’s ‘Greatest Welsh Novel’ series.

Jim Morphy is a critic and regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.