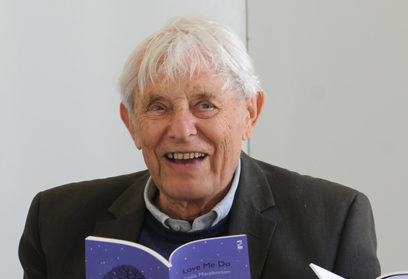

At Hay 2012, 89-year-old Dannie Abse CBE discusses his autobiography Goodbye Twentieth Century, which deals with survivor’s guilt and the changes the world has undergone.

Introducing the now 89-year-old Dannie Abse CBE, whose newly ‘bang-up-to-date’ autobiography Goodbye Twentieth Century is the 32nd and latest title in the Library of Wales, series editor Dai Smith cuts to the chase. Holding up a copy of The Western Mail, which he claims to have sneaked in ‘past the Telegraph’s spies’, he quotes the story on the back page – about Cardiff City’s change of shirt colour from blue to red – and says to Abse, a lifelong City fan: ‘What the hell do you make of that?’

‘It’s an existentialist problem,’ says Abse, ‘but I’m sure I’ll get used to it, just as I had to get used to the move from Ninian Park to the new stadium.’ It is a light-hearted moment – football is certainly cast into its true level of importance by some of what Smith calls ‘the miseries and tragedies’ that have blighted Abse’s life in recent years – but it does hint at something about the way the world has changed over the near-century course of Abse’s lifetime.

The reprint of Abse’s novel Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve made him the first living author in the Library of Wales’ ‘dead cast’ and the two men continue the discussion with an exploration of autobiography and fiction. Many readers thought that Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve was thinly veiled autobiography – including Abse’s own mother, who began to believe an incident in the book, in which Uncle Bertie gets into a fight, had really happened. Abse had totally invented it, but the use of real people’s names and the Cardiff in which he had grown up blurred the lines. Reading from his own Afterword, Abse cites a quotation from the Chinese painter Liaozhai – ‘it’s hard to paint a horse but damnably easy to paint a ghost’ – as evidence that ‘critics are more comfortable with the novel or play or poem that disguises autobiography’ than autobiography itself. It sounds like, Abse maintains, ‘a very narcissistic exercise’.

But in the case of Dannie Abse it is a very worthwhile one. Abse was a firsthand witness to the political tensions of the 1930s, watching his brother Leo take to the soapbox; he did his medical training in London, living among many refugees from Europe – including Elias Canetti – in Aberdare Gardens, Swiss Cottage; he met Dylan Thomas around this time; the house next door to his was bombed during the war. But Abse’s autobiography pivots on two tragedies: one universal, the other personal.

‘Auschwitz made me more of a Jew than Moses ever did,’ says Abse, a Welshman by birth and temperament but ‘a Jew as long as there’s one anti-Semite alive.’ There is a quiet but heartfelt murmur of assent from the marquee. Abse must be fairly unique in his upbringing; as a small child, when his mother wasn’t speaking English, he was never sure whether she had gone back into Welsh or Yiddish; she spoke both. ‘I’m ap Dafydd but also of David,’ says Abse simply.

Abse’s keen awareness – as a British Jew born in 1923 – of ‘survivor guilt’ was also brought into sharp, tragic focus by the death of his wife Joan, in a car accident in 2005. Bravely, Abse has not only written about the trauma and his grief in poetry and prose, but revisits the section of his autobiography here, reading about personal tragedy in front of a public audience.

For so many reasons, Dannie Abse is a remarkable writer and a remarkable man. We in Wales are lucky to count him as one of our own.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis

Photo credit: licensed by Daisyheadmaisie

You might also like…

Phil Morris recalls his thoughts on Dannie Abse’s Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve as the next contender in our quest to find the Greatest Welsh Novel.

Dylan Moore is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.