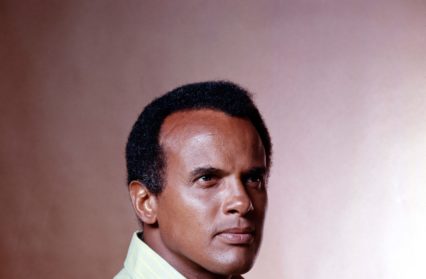

Phil Morris is at the Hay-on-We festival 2012 to hear a talk by Harry Belafonte, the Jamaican-American singer, songwriter, activist, and actor.

The majority of talks at the Hay-on-Wye festival feature a similar pattern of a preformed, condensed reiteration of the book’s themes, a rueful whinge at the length of the writing process and a few apparently self-deprecating jokes that actually speak to the author’s rampant egotism. In the case of Harry Belafonte, we got to hear from a man whose greatness matches that of the story he has written, because that story is his life – a life that extends deep into the last century, and which was party to its many ideological struggles and defining transformations.

Harry Belafonte was born in a ‘ghetto within a ghetto’ in the New York of the 1920s, but he was raised, for the most part, in Jamaica from where his parents originated. His mother, Melvine, was the predominant formative influence on his life, in which his errant father played only an occasional role. She is recalled as someone who suffered ‘oppression as a woman, not only as a black person’ but also as someone who ‘endured’. The word endurance is one that crops up repeatedly in Belafonte’s discourse; it seems to be the best and sincerest compliment he can bestow on the good and the great he has known throughout his long life. He speaks with the measured cadences of writerly prose. The care and precision with which he selects his words may, in part, be attributable to the importance of rhetoric to his many campaigns for civil rights; it may also partially result from his dyslexia, which caused him to leave school with ‘a level of intelligence that was attractive yet unfulfilled.’

A political education was provided by the U.S. Navy, in which Harry Belafonte served during World War II. At this time, American military personnel were still segregated along racial lines. Belafonte recalls with understandable, though understated, bitterness how many African-American, Hispanic and Asian veterans returned from that war to receive ‘no generosity from those who conscripted our services and put us to the task.’ His developing political consciousness was heightened upon joining the American Negro Theatre, which was housed in the basement of a public library building in New York. Belafonte worked there as a stage-hand, taking the occasional acting role when required. It was among this tiny community of African-American theatre artists that he had his ‘first real epiphany’ – an experience of the transformative properties of art. One night, Belafonte saw, sitting in a capacity audience of fifty people, the ‘great icon, great force’ that was Paul Robeson, who spoke to the cast after their show, inspiring them with the notion that ‘artists are the gatekeepers of truth.’ A lifelong friendship with Robeson ensued, and the sense of mission that he instilled in the young Harry Belafonte is palpable even today.

To further his career as an actor, Belafonte enrolled in the Dramatic Workshop established by the émigré theatre-director Erwin Piscator in post-war New York. His classmates comprise an astonishing array of talent including Marlon Brando, Walter Matthau, Sidney Poitier, Tony Curtis and Bea Arthur. Unlike his contemporaries, who formulated a new ‘method’ acting style for American film and television, Belafonte gained renown as a singer. He began his musical career by singing in Jazz clubs to pay for his acting lessons – sometimes backed by the likes of Charlie Parker and Miles Davis. With the offer of a record contract from RCA he searched for a repertoire, ultimately plundering his youth for the calypsos of the Caribbean that became ‘the passport to [his] success.’

It is a paradox of Harry Belafonte’s career, not lost on him, that he became immensely successful – becoming the first artist to sell one million copies of a single album Calypso – with the songs of poor Jamaican plantation workers who ‘sang when they worked, sang when they were sad.’ His fame came quickly and was global; he remembers with a wry smile that he has ‘never seen anything as strange as 50 000 Japanese singing Day-O.’ Yet whereas many superstars simply relish the wealth and privileges that come with their fame, Belafonte asked himself this question, ‘What can I do with this kind of power?’ Art could never be a matter of self-aggrandisement; Robeson’s message that art can ‘inform and instruct’ as well as entertain provided the answer.

Until the election of President Obama in 2008, the ostensible leadership of African-Americans has rested upon religious and cultural figures rather than elected representatives. The power of Belafonte’s celebrity in Eisenhower’s America – he was being paid more than Frank Sinatra for his Vegas shows in the late 50s – leant considerable weight to the emergent Civil Rights movement.

His standing within the African-American community led the then Senator John F. Kennedy to visit him to secure his support ahead of the1960 presidential election. Belafonte initially refused, advising Kennedy to talk to ‘my friend’ Martin Luther King to learn more about what black Americans wanted from a future administration.

In spite of the significant changes that Harry Belafonte has helped to bring about, he reflects ruefully on contemporary America, observing that ‘as diverse it is in its population, as narrow the nation is in its thinking.’ And yet these do not sound like words of resignation and defeat, but more like a renewed call for a participatory citizenship that will answer the challenges of racism and poverty. There is an implicit demand for other artists to follow his example, as he explains, ‘There was always this knock at the door, and I always answered.’

Ultimately, it proves impossible to encompass the full magnitude of Belafonte’s life and legacy within the scheduled one-hour conversation, nor indeed is it possible to do so in a single review; but some measure of the man’s journey through history is provided when David Lammy concludes the talk by speaking of Belafonte’s sponsorship, with Eleanor Roosevelt, of a student exchange programme that enabled African post-graduates to study in the U.S. One of those students was one Barack Obama Senior. So while he continues to rage against injustice and inequality, the chief impression one takes away from Harry Belafonte is one of decency, compassion and optimism. In short, he endures.

Recommended for you…

Dylan Moore is at the 2012 Hay Festival to hear a discussion between George Alagiah and Sarfraz Manzoor based on Alagiah’s BBC documentary Mixed Britannia.

Phil Morris is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.