Dylan Moore was on hand to witness a discussion concerning Inventing the ‘Infra-

‘I started calling it an infra-

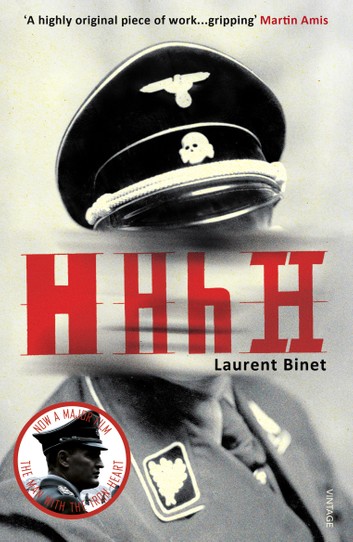

Trying to explain the intricacies of fiction, faction and fiction based on fact, the French novelist whose debut is HHhH – about Reinhard Heydrich, architect of the ‘final solution’ –

Trying to explain the intricacies of fiction, faction and fiction based on fact, the French novelist whose debut is HHhH – about Reinhard Heydrich, architect of the ‘final solution’ –

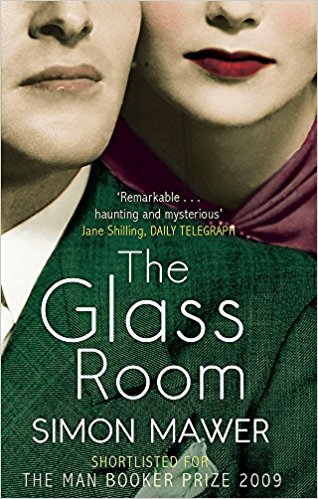

Ten years in the making, Laurent Binet’s novel is intricately researched and – as far as possible – is based on real events. He tried, he claims, to ‘resist the novelist’s temptation to invent.’ Simon Mawer had no such qualms. For the writer of Booker-

His latest novel, The Girl Who fell From the Sky, about a 19-

His latest novel, The Girl Who fell From the Sky, about a 19-

The different approaches and attitudes of the two writers, not to mention Mawer’s tempered demeanour and short silver hair contrasted with Binet’s rock star looks, expansive gestures and often carried-

Simon Mawer says it ‘was an extraordinary time… which you need to understand to understand Europe today’. The generation gap between the writers means that Mawer’s father served in the British special forces while Binet relied on the stories of his grandfather, who became a POW in Germany. ‘I am of the last generation to hear from a direct witness’, says Binet and it is clear that part of his project is passing on the baton for future generations to understand. It comes up, almost in passing, that his mother is Jewish. Binet claims this is little to do with his motivation for writing the book, but given that he devoted ten years of his life to the project, he concedes: ‘I don’t know what a psychologist would say.’

What is clear throughout this session – and indeed the one that preceded it [Niklas Frank talks to Philippe Sands] – is that however we tread the borderline between fact and fiction, what we can never afford to do is fail to distinguish between truth and lies.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis