Adam Somerset is at the Hay-on-Wye festival 2012 to hear a talk between Rolf Heuer and Simon Singh about CERN and the Higgs Boson.

Some things at Hay Festival are perennial, comfortingly so. There is sight of the hip editor-cum-television personality who stands out, as ever, on account of the hair which extravagantly reaches out several inches above the height of all of Hay’s other surging attenders. There can be few places on earth where on a Spring Holiday Nobel prize-winners rub shoulders with comedians, where an historian is seated, signing her new book, a few feet from a great gardener or a former head of the Royal Society. This is Diamond Jubilee year and in a week devoted to celebration of the sheer us-ness of being British, the maes at Hay exudes an intoxicating air of borderless internationalism.

Rolf Heuer has been Director-General of the CERN project since 2009. He could well be a business school case study of what marks out leadership from professional practise. He has been at Hay before and some in the audience are repeat attenders. Among Hay’s sheer torrent of events this stands out on at least one count. The discussion centres on a subject which must stretch, or even elude altogether, the comprehension of many listeners.

In Simon Singh’s sheer excitement for the Higgs Boson he is everything a speaker might wish for, broad, informed, modest. Questions from the audience jump on this mysterious particle, which may or may not even exist. Dr Heuer is strikingly lucid. On the scientific method he describes how experimental work is, as a matter of practice, open to fierce internal critique, how result on result builds less to establish fact than to drive out error. One experiment, which gave a paradoxical result of questioning relativity, was found to be due to a faulty screw. In this case a particle had arrived at a point paradoxically ahead of all expectation. The experiment, which was located was Italy, had aroused scepticism. ‘After all,’ Heuer reports a lead Italian physicist commenting, ‘nothing in Italy ever arrives ahead of time.’

In the midst of economic calamity Europe possesses a scientific project with a plan and programme of work already mapped out to 2030. It is reassuring that humankind can still organise itself for a gigantic common enterprise of enquiry into the universe’s fabric.

An aspect of leadership is the ambassadorial role and Dr Heuer is a masterly communicator. Simon Singh repeatedly states that he is just the science writer, not the real thing. All endeavour needs interpretation and wider communication; Singh’s stance as observer could be well be followed by certain grandstanding media folk who imagine themselves their subject’s equivalent.

Times are tough and Rolf Heuer is inevitably asked, ‘What is CERN for?’ ‘It is first knowledge,’ he says, ‘and knowledge must have practical application. What I cannot say is when.’ Heuer is sharp on practical example. ‘It took forty years for Dirac’s paper on anti-matter to find its application in medicine in positron emission tomography.’

Hay has as an afternoon attraction in Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman. His book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, is a popular – and highly recommended – summation of a lifetime’s work on the fallacies in human thinking. Heuer knows it either through study or experience. He knows that the human mind needs concrete example. Here he describes meeting fellow German scholar and intellectual, Joseph Ratzinger, now elevated to the papacy. They meet to discuss how theology might set about a language for the sub-atomic world. The Higgs and the Divinity are after all alike in their qualities of ineffability.

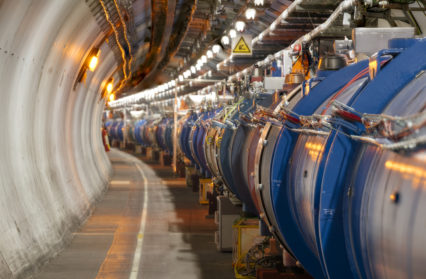

The human mind makes comparison of like with like. The licence fee is Europe’s sensible mechanism for television as a public service. Its spokesmen often, however, ignore psychology and attempt to link its cost to the price of beer or bread. Like needs to be compared with like. Quizzed on the cost of CERN’s many kilometres of accelerator tunnel Heuer says it plainly ‘the budget is about the same as the University of Cambridge.’

As for how to win an audience Donald O’Connor sang it back in 1952 in Singing in the Rain. Like the quip about Italy, Rolf Heuer knows how to ‘Make ‘em laugh.’ He leavens explanation and justification with the odd one-liner. Swabia is Germany’s workhorse and the butt of much humour from the country’s other regions. ‘I am a Swabian,’ he says in response to a question on a particular course of action; ‘I only bet when I am sure of the outcome.’

Adam Somerset is an essayist and a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.