31/5/13: Discussion with John Berry, Artistic Director of ENO, Phelim McDermott, Director and Dan Potra, Designer, about The Perfect American / solo piano recital featuring Philip Glass.

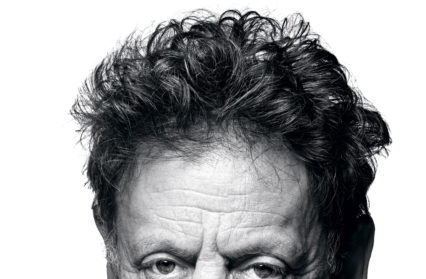

I was conscious that the audience for the Philip Glass event at the Hay Festival was, in the main, extremely reverential and afterwards I pondered why this was so. I concluded that, when people are told that a man is one of the world’s most important (living) composers, they accord him an almost mythical status, and it is difficult for them to see the man behind the mask they create for him.

What Hay offers is an opportunity to get a sense of a person, to see past the fame and the reputation. Listening to Philip Glass in conversation with people with whom he has collaborated on his new opera The Perfect American (which received its UK première at ENO the night after this event), I thought him a very likeable man, certainly not ego-ridden. Perhaps this is what has drawn so many people from different musical and creative backgrounds to work with him, including Paul Simon, David Bowie and Doris Lessing. Collaboration was one of the big topics of the discussion at Hay. In composing the music for The Perfect American, Philip Glass worked from visual images produced by the designer Dan Potra, collaborating, as he said, ‘through the medium itself’ – he ‘simply’ looked at the pictures and wrote the music.

Walt Disney himself, an imagining of the final months of whose life is the subject of this opera, produced his work in collaboration with others. This is not just because animation requires a team, but because Disney was famously not good at drawing: it was others who produced the iconic outlines of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, which Disney then traced over. However the cartoon characters themselves were not what attracted the interest of the creative team. What they have looked at, they told us, is the process of animation, its patterns and repetitions, something which is entirely in line with the structure of Philip Glass’s music (or at least, that which he has written to date) with its repetitions of rhythmic ‘cells’.

In the concert which followed the discussion, Glass played music from his repertoire for the piano. Described in the Hay programme as ‘classic’ repertoire, this music (Mad Rush and sections of Metamorphosis and Etudes) was all in the well-trodden minimalist tradition. When I closed my eyes whilst listening, I began to conjure up flickering animations silhouetted on a cinema screen. Whether or not the music for The Perfect American is cast in the same mould as the music Philip Glass played us I cannot yet tell you. The TV/radio presenter and writer Clemency Burton-Hill who ably chaired the discussion, mentioned reports following the world première of this work in Madrid in January, that the work is ‘melodically richer’ than Glass’s music heretofore. Clearly composition comes easily to him, but without the different stimuli of working in collaboration with people from different traditions and disciplines, he would, on his own admission, still be writing in the vein of Einstein on the Beach (1976). He endeared himself to me with his observation that approaching the work (of composition) with curiosity and trust (of collaborators) means that ‘you may end up with something you didn’t think you were going to do.’

We were given no aural clues at Hay as to what this ‘something’ might be in The Perfect American, but there were some visual ones. Images projected of some of the early designs and story boards for the ENO production featured creatures. Not Mickey and Donald (the copyright on whose images is fiercely defended) but imaginings of the animateurs, who tended to put their own gestures into their animations. So we can expect to see the stuff of dreams and mythical stories. Walt Disney was fascinated by cryonics, seeing it as a way of living for ever, though of course he actually lives on in his animations! Philip Glass describes myth as ‘something not true that keeps happening’; I would say that it is about archetypes which are in us all, which is why we relate to them so strongly. Fairy stories present us with these archetypes, and, when they are set upon a stage, their power is intensified and can make us laugh and cry and, most importantly, think afterwards.

Philip Glass said at Hay that text, image, movement and music together are as earth, air, fire and water. As the latter have been considered to be building blocks of life on earth, the former are the essential components of opera. When he was asked what had drawn him to Walt Disney as a subject for opera, he said that he was attracted to people who had their feet in the mud and their head in the clouds. Perhaps this is because he shares those qualities. No more than Walt Disney is he a ‘perfect’ American, but he is a most fascinating one, who will certainly continue to attract an eclectic range of other creative people to work with him in the future. Judging from the rapturous applause which greeted Philip Glass’s encore – Closing from Glassworks (1981) – many in the Hay audience would like to preserve him as he was in the twentieth century. Personally, I look forward to his new music and fervently hope to be surprised.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis

You might also like…

The market town of Machynlleth has been host to an annual music festival since 1987 and this year’s programme, with its assembly of Welsh and international musicians, continued to offer an exciting mélange of chamber and vocal music.

Cath Barton is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.