‘Historians are there to put in the complications’. The speaker is Peter Stead: ‘Our role’ he continues ‘is to bring complexity’. The setting is a misty Saturday morning at the Hay Festival and a panel of three historians and a journalist has come together to discuss Welsh history. Hay 2012 is host to six start-of-day debates, which range across culture, sport and soldiery. H.V. Bowen of Swansea University is Chair of the first event and editor of Gomer’s new collection of twenty-four accompanying essays.

The book, a collaboration between the press and academic body History Research Wales, is unique according to Bowen’s Acknowledgement. The essays first appeared in the Western Mail in Spring 2011. Beginning with Saint Cadoc and ending with Rhodri Morgan and Dafydd Iwan, they take in teachers, cyclists and rugby players.

Peter Stead provides an introduction in which he reiterates his stance on the public platform: ‘History is a battleground.’ He cites a conservative politician who was spurred, ironically, into public life in reaction to Aneurin Bevan. ‘Of course,’ Stead writes ‘one man’s hero is another’s villain.’

If one figure were to exemplify the ambiguity of history it would be Sir Thomas Picton. Memorialised in marble in Cardiff’s City Hall as a Welsh hero, he is eulogised by Terry Breverton in his idiosyncratic ‘Wales A Historical Companion’ (2009).’ ‘Popular with his men and the British public’ he writes, and again ‘loved by his men.’

By way of riposte Chris Evans describes here, in horrible detail, the torture and atrocities presided over by Picton during his governorship of Trinidad. One of the great scandals of its age, his guilt under British law was over-turned at a retrial. The argument of his lawyers was that his acts were to be judged under the Spanish law then prevailing, which permitted torture.

by H.V. Bowen

200pp, Gomer, £14.99

Not all the book’s essays follow this unsparing forensic model. An essay on the miners is a record of pride and solidarity. The Battle of Orgreave is retold in detail but the author is silent where Jon Gower is forthright. In his own recent ‘History of Wales’ he writes ‘The killing of David Wilkie was a tragedy and a public relations disaster for the NUM.’

On George Thomas Paul O’Leary captures the contradictions of a life in public service. He cites Leo Abse on his friend and ‘the thin ice on which he skated all his life.’ It is a fuller record than Terry Breverton’s acidic comment that ‘Lord Tonypandy was treated like a demi-god by the media in Wales. He was ‘deeply religious’ but this author has no desire to go to the same place as the ‘right honourable’ Thomas.’

A gathering of historians of this stature is bound to produce much of interest. Helen Nicholson writes of the Hospitallers at Slebech in 1388 complaining to their headquarters in Rhodes about the cost of accommodating the excessive numbers of travellers en route to St David’s. Oliver Cromwell was responsible for re-admitting Jews to Britain three hundred and fifty years after their expulsion. As MP for Cambridge he petitioned Parliament on behalf of puritans in Monmouthshire and later was active on behalf of the same group in Pennard on the Gower.

H.V. Bowen tells how Copperopolis Swansea at its peak was sourcing the metal not just from Parys but from Valparaiso in Chile and Burra in Australia. Paul O’Leary again describes how the anti-Irish riots stretched from Cardiff to Holyhead. Irish immigrants, used as ballast on returning coal ships, would be offloaded on lonely stretches of coast to offset official and popular hostility. Iolo Morgannwg in 1799 made comment that ‘an Irishman’s loves are three: violence, deception and poetry.’ Ivor Novello, originally David Ivor Davies made such a poor pilot that he crashed two planes before the Air Ministry gave him a desk job.

On the panel at Hay Richard Marsden takes the debate into the territory of history versus heritage. Heritage, he says, always takes place in the present. National heroes tell us more about now than then and mirror ‘ who we feel or aspire ourselves to be.’ One strand of heritage is always seeks to portray its subjects’ innocence and virtue. Chris Evans in his admirable ‘Slave Wales’ (2010) describes how the pans and stills for the Caribbean sugar industry were wholly dependent on Anglesey-mined copper. Here the reader learns that it was Welsh copper companies who developed Cuba’s El Cobre mines to be worked by slaves.

The essays have been transposed in unaltered form from newspaper to book. A few informalities would have been better deleted. St Beuno receives a miraculous cloak to keep out wind and rain; to this is added ‘as he had gone to live in Snowdonia, this must have been very welcome.’ A mediaeval prince ‘left a blood-soaked trail worthy of any modern Tarantino movie.’ Henry II of England is ‘politically savvy.’ Mention of the Crimea War’s Lord Lucan has in brackets the rather jejeune ‘no, not that one.’ An aside says that Tony Richardson’s 1968 of the Light Brigade is ‘worth an evening of your time’

The coverage is not inclusive. Peter Stead in his introduction calls for a more measured appreciation of industrial leaders. Robert Owen is in, but Lord Rhondda, the Marquess of Bute and David Davies not. Saunders Lewis and Ambrose Bebb are missing. Wyn Roberts and Emlyn Hooson are in but not the Kinnocks.

The selection includes an essay on disease, hauntingly illustrated by an upland cholera cemetery in Tredegar. The essay records rightly the steady conquest of acute disease and culminates in the foundation of the NHS. However, its inclusion is slightly ill-fitting. The causes of ill-health have been displaced. Wales and Scotland regularly vie for Europe’s worst health profile depending on the criterion used. Depression’s incidence is as great as any preceding condition. The time bomb of diabetes is set to dwarf previous incidents like Tenby’s 1650 outbreak of plague.

David Lowenthal in his ‘The Past is a Foreign Country’ (1986) describes the past as being ‘largely chaotic and episodic, a hodge-podge of chronologically unknown or mistakenly connected figures and events. In this heaving and formless sea stand a few islands of stratified narrative, on which we huddle for calendric security.’ In this vein Richard Marsden re-characterises Gerald of Wales as ‘vain, self-aggrandising and occasionally self-delusional’ with a life ‘politically aligned with the English church and the English monarchy.’ For an example of the sheer caprice of history’s judgement Lloyd Bowen describes Cromwell’s enrolment in Victorian Wales as a national hero. For the Tory-inclined Western Mail ‘the butcher of Drogheda and Wexford’ becomes the ‘Gwroniad Rhyddid.’

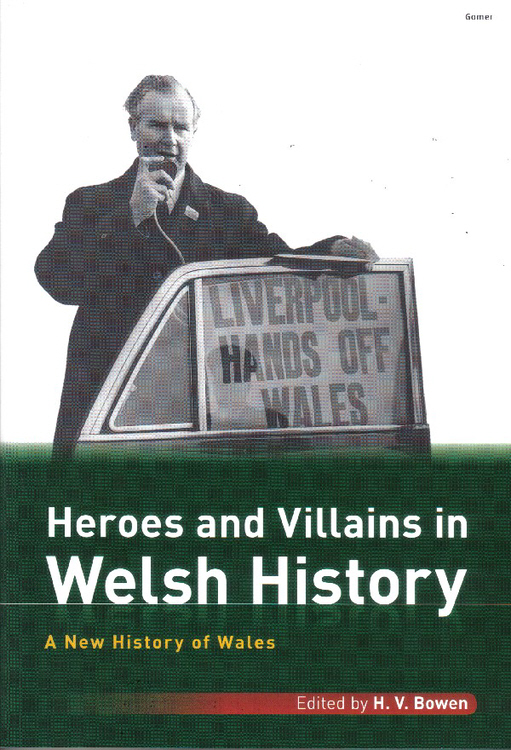

Gomer’s designers have added eighty-six pictures to the essays. Abbeys and castles, ministers and cyclists, sculptures and stained glass windows all feature. Desolate pictures of Iscoed, Lleweni Hall and Ruppera Castle have been borrowed from Gomer’s admirable ‘The Lost Mansions of Wales.’

Noel Thompson recalls an 1892 speech by MP Tom Ellis to students at Bangor. He looks to heroes to carry the Neges Cymru. Robert Owen, he declares to be ‘a strong, strenuous fertile-brained Welshman’, fit to stand alongside Plato. The best virtue of ‘Heroes and Villains in Welsh History’ is that it invites the reader to share in the inconsistencies of judgement that the present bestows upon the past.