Jim Morphy delves into HHhH the “brilliant, and highly-

In July 1941, Heinrich Himmler received news that the plane of a high-

Binet’s girlfriend had wanted this sentence erased from the book. ‘You’re making it up’ she told him. He initially took the advice, seeing that he had no way of being certain about the symptoms of the panic: how did he know Himmler’s face had turned red not white? How did he know what the Nazi had felt? The author accepted he was guilty of writing something that was a perfect example of the ‘puerile, ridiculous nature of novelistic invention’ that he himself so despised. He removed the sentence, and tried a few more-

We know of Binet’s exchange with his partner not because he described it in a media interview about his much-

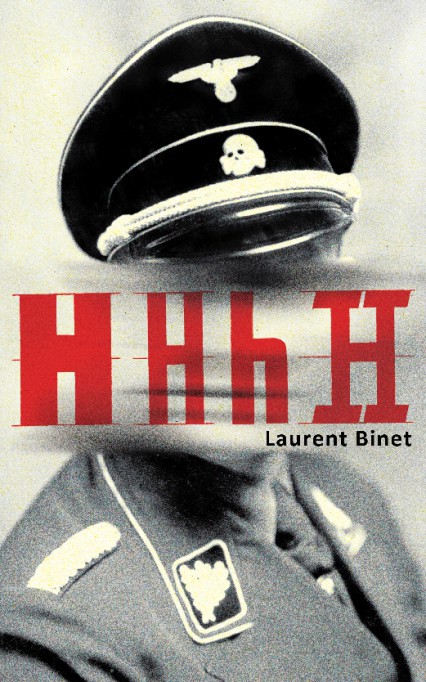

by Laurent Binet

pp.366, Harvill Secker, £16.99

In essence, this is a novel of two parts: one telling a true story from World War II, and, interwoven with this, another in which the narrator provides a commentary on the writing of the story itself. Post-

The historical narrative is centred on the Nazi who survived his aforementioned plane crash: Reinhard Heydrich, ‘the most dangerous man in the Third Reich’. Himmlers Hirn heisst Heydrich –

Having been dismissed from the navy aged 27, Heydrich went on to lead the Nazi Security Service, to be one of the architects of the Holocaust, and, at 37, to become Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, presiding over much of what had been Czechoslovakia. The unimaginable horror of his rule led him to be known as ‘the hangman of Prague’.

As Laurent Binet neatly describes, Heydrich’s notoriety marked him out as a target for the Czechoslovak President-

Following instruction from Benes, and training by British forces, the pair were parachuted into Prague in 1942 as part of Operation Anthropoid. They lived undercover, thanks to the bravery and ingenuity of members of the Resistance, while waiting for their chance to kill Heydrich. After the assassination attempt, the two then became the hunted. Their fates inevitably to be decided by gunfight. By the time of the book’s later chapters, it has become classic edge-

But telling the story straight was never going to be enough for Binet. The narrator muses interestingly about his neurosis in fictionalising real, important events. He discusses his literary and ethical concerns with previous cultural representations of Heydrich, Gabèík and Kubiš, and history, in general. Chatty descriptions of research visits to museums and landmarks provide both pathos and amusement.

Without doubt, many will dislike the literary games being played here. In particular, the narrator’s habit of correcting things he’s said earlier, as if it’s all been written in one take, proves one trick too far. But those willing to get on-

Quibbles aside, this is a magnificent effort. Laurent Binet succeeds so daringly, and so successfully, it is difficult to believe he has any of the self-