Welcome to Wales Arts Review‘s look back on the cultural highlights of 2017, a tour of the moments that have lifted up the year for some of our top contributors.

Niall Griffiths

My highlight of 2017 was the fact that it wasn’t 2016, although the shockwaves continue to shudder, and will do for some time. And a trip to Mostar will forever be remembered; poetry and beer amongst war damage, and proof that depravity can, eventually, be overcome (and I’m writing this on the day that Ratko Mladic received a life sentence). Oh, and I’ll never forget a minor miracle; on a train journey in the summer I saw, outside the window, a huge field, empty except for one rock, and on that rock was a single duck.

Steph Power

My highlight of 2017 is not a single work but a coupling of two powerfully together – although I could equally have chosen either in its own right.

All year, but especially last October-November, Wales reverberated with commemorations of the centenary of the 1917 Russian Revolution. Unsurprisingly, there is a dearth of Soviet opera about the Revolution; life was dangerous enough for composers living under Stalin. Nonetheless, within a highly intelligent triptych of revivals at Welsh National Opera (which included Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin), two operas yielded especially fascinating insights into the volatile political and cultural ferment from which that cataclysmic event finally erupted: Musorgsky’s mighty unfinished historical epic, Khovanshchina (1872-1880), and Janáček’s From the House of the Dead (1927-8).

Khovanshchina is one of the most extraordinary examples anywhere of political discourse writ dramatically large. The eloquently sprawling plot relates how aristocrat conspirators failed to depose the reforming Tsar Peter the Great in 17th-century Russia – and director David Pountney revived his deeply thoughtful, Soviet-inspired 2007 production to compelling effect.

With lethal factional infighting and twisted religious extremism, the wider relevance of the opera to present times became brutally clear. As a metaphor for any people’s fate, it was utterly chilling. But a phenomenal cast, chorus and orchestra under conductor Tomáš Hanus ensured that colour and strength, as well as agony, shone through Shostakovich’s marvellous 1958 orchestration, utilising Stravinsky’s finale.

From the House of the Dead may have been penned by a Czech, but Janáček was a lifelong Russophile, and his adaptation of Dostoyesvky’s semi-autobiographical account of life in a Siberian prison-camp cuts right to the socio-political bone. And it does so employing radical music-dramatic means that astonish in their aesthetic proximity to an elder composer whose music he encountered only late in life.

The striking echoes between the Janáček (designed by the late Maria Björnson) and Musorgsky (designed by another sadly missed: Johan Engels) were captured with sweeping cinematic skill by director Pountney and conductor Hanus. These productions may have been revivals – the latter first sung in English 10 years ago, and the former venerable at 35 years old (marking further, personal anniversaries for Pountney, who turned 70 in the autumn) – but the drive and intensity brought to each made for a doubly shattering experience.

There was a critical first here, too: From the House of the Dead was Janáček’s final work, and he died without hearing it. For decades, it was assumed that his near-illegible manuscript was unfinished, and his students misguidedly padded out the instrumentation. It has taken until now, thanks to painstaking work by musicologist John Tyrell, assisted by the late Sir Charles Mackerras, to restore the piece to Janáček’s authentic starkness. Sung and played with hair-raising power under Hanus – who hails from Janáček’s home town, Brno – the heightened astringency of registral extremes brilliantly catalysed the drama from tinnitus-high piccolo to sepulchral contrabassoon.

While a Siberian prison camp might seem the bleakest of choices for an opera setting, thanks to the entire team’s breathtaking combination of rawness and gentleness, the work soared as a paean to the human spirit and its capacity for compassion even at its most desperate or depraved.

John Lavin

While Robert Minhinnick’s Diary of the Last Man is rooted in the dunescapes of the author’s hometown of Porthcawl, it is also a work that is intrinsically internationalist in outlook. The long title poem is a wry, standing-ovation-worthy requiem for humanity predominantly set on the Welsh coast but it could be argued that Minhinnick reserves his most powerful poetry for when he casts his eyes abroad.

The searing ‘Amiriya Suite’ revisits ‘a bunker in Baghdad destroyed by the USAAF on February 13, 1991’, in which ‘over 400 civilians were killed’. The reader is introduced to a female survivor that acts as a tour guide to the ‘charnel corridors’: ‘one body with four hundred souls.’ The collection draws to a close with ‘Aversions’, a series of translations / interpretations of Welsh, Arabic and Turkish poems, all of which conjoin with the rivers of desolation that sit at the heart of Minhinnick’s poetic vision. It is the two poems from Turkish author Nese Yasin which really leave bruises on the heart, however. ‘Aleysha’, in particular, is hard to bear, as a beloved dead daughter is recalled like ‘a name… in a story book’. Yasin / Minhinnick masterfully convey a reality so full of pain that it seems barely plausible.

The searing ‘Amiriya Suite’ revisits ‘a bunker in Baghdad destroyed by the USAAF on February 13, 1991’, in which ‘over 400 civilians were killed’. The reader is introduced to a female survivor that acts as a tour guide to the ‘charnel corridors’: ‘one body with four hundred souls.’ The collection draws to a close with ‘Aversions’, a series of translations / interpretations of Welsh, Arabic and Turkish poems, all of which conjoin with the rivers of desolation that sit at the heart of Minhinnick’s poetic vision. It is the two poems from Turkish author Nese Yasin which really leave bruises on the heart, however. ‘Aleysha’, in particular, is hard to bear, as a beloved dead daughter is recalled like ‘a name… in a story book’. Yasin / Minhinnick masterfully convey a reality so full of pain that it seems barely plausible.

Sally Rooney’s first novel, Conversations with Friends, is one of those irresistible, instant-classic debuts like The Rachel Papers or The Buddha of Suburbia: works that from the first line onwards drag the reader, whether willingly or not, into the world of their idiosyncratic narrators and never let go. The novel revolves around a young poet’s affair with a married man, a subject that could be hackneyed in the hands of a writer with less talent, but the relationship is conjured with considerable perception, imagination and panache. Rooney is particularly good at writing about sex from the female point of view and the novel is full of urgent news about what it is to be a young woman in the 21st Century.

Last but by no means least, 2017 saw the publication of short story collections by two of my favourite exponents of the form. Nuala O’Connor’s Joyride to Jupiter and Sarah Hall’s Madame Zero are the work of artists very close to the peak of their powers. O’Connor has blossomed into an author of great empathy and sensuality, writing with a breadth of vision that skewers contemporary Ireland, taking in everything from dementia and immigrant hotel workers to Dublin millennials and their relationship with the crumbling edifice of the Irish Catholic Church.

If Hall’s previous collection, The Beautiful Indifference, was an uncompromisingly realist affair, Madame Zero sees the author move confidently into the realm of the dystopian and the magical realist, creating some of the best 21st Century short stories to date in the process. From the beautifully realised Angela Carter–meets–Kafka stylings of opening story ‘Mrs Fox’ to the sinister, political eroticism of the startling closing piece ‘Evie’, these stories really are that good.

Siân Norris

This year, I read three novels which dealt with issues of male violence in stunning and frightening ways. They were When I Hit You by Meena Kandasamy; Birdcage Walk by the late Helen Dunmore, and First Love by Gwendoline Riley.

Their publication made me realise we have a real dearth, it seems, of literary fiction that deals effectively with male violence from the women’s perspective.

When I Hit You by Kandasamy is subtitled ‘Portrait of the writer as a young wife’ and graphically describes a violent marriage. Kandasamy deftly illustrates the build-up from controlling behaviour to abusive language, physical and then sexual violence. She explores how hard it is to leave, and how those around an abusive man collude with him to allow the violence to continue. What is particularly devastating, although sadly all too familiar, are the voices of her family urging her to stay and make the marriage work.

When I Hit You is very difficult to read in places, and the imagery she uses to describe, for example, the rapes her husband committed, haunt you for days — if not months — after. But this is not simply a litany of violence and horror. Kandasamy explores how writing and art offered her a sanctuary. While her husband tried to diminish and erase her, she wrote and wrote and wrote — deleting everything at the end of each frantic typing session. Through that act of writing, she was able to hold on to her sense of self and identity, and eventually escape.

Both Birdcage Walk and First Love deal with coercive control, and the first is one of the best examples of how to write what remains a little understood or explore aspect of male violence. Set in Bristol in the 1790s, a young wife Lizzie becomes increasingly frightened and trapped in her marriage with a failing builder. Dunmore deftly explore how the insidious thing about controlling relationships is that one doesn’t realise how dangerous it is, until fully enmeshed.

Birdcage Walk was Dunmore’s last novel, and showed a writer who really was at the height of her storytelling powers.

Gary Raymond

It has been an unexpectedly good year for the essay. I’ve never held much credence to the commonly-held opinion that Martin Amis is one of our great novelists, but I am now convinced he is one of our great non-fiction writers. To my shame, this had genuinely passed me by until The Rub of Time was published this year. Amis’ insight, his style, his swagger, is awesome on an almost page-by-page basis. His article on the O.J. Simpson trial is as entertaining and cutting as non-fiction gets. His afternoon with John Travolta is one of my favourite things I’ve read this year. He’s also a first class literary critic. I get the feeling he’s not quite as politically astute as his old partner-in-crime Christopher Hitchens – Hitch was evangelical, but Amis seems to have political opinions out of some obligation to his role as Man of Letters – and perhaps his baggage is a little less weighty than Hitchens’, but as a stylist he is up there. Some of the work is slightly dated – he is heavily indebted to the great American writers of the twentieth century – Bellow, Roth, DeLillo etc. – and these pieces, some older than others, feel like a smoke-shrouded conversation from a different night, what with all the immediate problems of the world. These writers may have predicted where we’re at, but let’s talk about those who are going to help us retain our sanity while we get out of it.

A very different collection is J.M. Coetzee’s Late Essays 2006-2017. A very different style indeed. This seems weightier still, and very much lacking any sense of fun that you find with Amis. But Coetzee is one of the towering figures of literature, and another great essayist. It was good to see University of Wales Press publishing All That Is Wales: The Collected Essays of M. Wynn Thomas – Wales needs to put more emphasis on the published work of its most respected public intellectuals, and that is certainly what books like this do.

Julia Forster

A highlight month every year in mid-Wales is May: we have the Machynlleth Comedy Festival to kick off the month, book-ended at the other Bank Holiday weekend by the folk festival Fire in the Mountain, held just south of Aberystwyth.

A stand-out gig from the comedy festival this year was the improv group Austentatious; they improvised a complete story, in the style of Jane Austen, based on a title which was plucked from a hat having been written by a crowd member: Mike Pence and Sensibility; I particularly loved the improvised cockney-accented character played by Cariad Lloyd. James Acaster Babysits also had me in stitches. This show, also improv-based on audience participation, sees James make up a story based on characters and plot points given to him by the kids watching the show. It descended – as you’d expect – into absolute anarchy. By far the best show I’ve seen in the many years of Machfest.

In March, I went to the open studio of the portrait artist Daniel James Yeomans who is based just outside Newtown in Llandyssil. Since then, I have been going back regularly both as a sitter for a charcoal portrait, but also to take my ten year-old daughter for a study he’s in the throes of finishing. It has been a privilege to see an artist at work who has been schooled in a method of painting which has remained largely unchanged for centuries, the sight-size technique. One of the highlights of the process was the day my daughter asked Daniel to paint a portrait of her stuffed toy mouse on a miniature canvas, measuring just three inches by five inches.

Something I’m looking forward to exploring is the new digital magazine Boundless – an off-shoot of the crowd-souced publisher Unbound – which is commissioning long-form journalism and which launches in December. I am particularly looking forward to reading Alex Clark’s forthcoming interview with Siri Hustvedt as I am currently enjoying Hustvedt’s latest book of essays, Living, Thinking, Looking (Hodder & Stoughton). I am also eagerly awaiting what Jo Bell and Jane Commane – plus contributors – have to say on the art of being a poet; How to Be a Poet (Nine Arches Press) is published in early December, and I will be making some New Year’s writerly resolutions for 2018 based on this guide, I’m sure.

Julia Forster is an award-winning author of fiction and non-fiction and works in PR for independent presses. www.julia-forster.com

Durre Shahwar

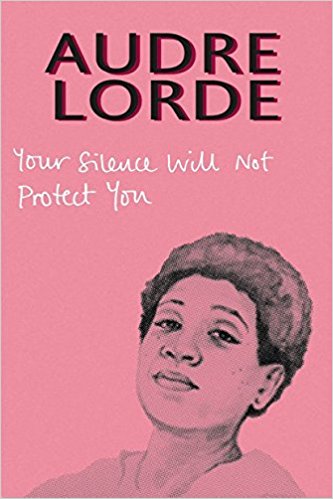

To say it has been a year of reading great books would be flippant – isn’t every year? But there has been something in books this year that has seemed urgent, reactive, demanding. I suppose ‘protest literature’ is the right term for it. From Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire to Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West. From politically charged and much-needed anthologies such as Nasty Women by 404 Ink and Dead Ink Books’ Know Your Place (shameless plug). Yet among it all is the publication of some of Audre Lorde’s Your Silence Will Not Protect You by Silver Press that brings together some of the author’s well-known essays and poetry in one place.

This is also perhaps the first time that Lorde’s work been published by a British publisher – a fact that raises many questions in itself. And until it, I am ashamed to say, I had not read much Audre Lorde besides what could be found on the internet. But I am glad to have corrected this. Black, feminist, lesbian, poet, mother, activist, essays; Lorde embodied and owned all of these self-identifying titles. Her belief in the power of language, of speaking out and confronting injustice rather than staying silent, woke me out of my own silence.

This is also perhaps the first time that Lorde’s work been published by a British publisher – a fact that raises many questions in itself. And until it, I am ashamed to say, I had not read much Audre Lorde besides what could be found on the internet. But I am glad to have corrected this. Black, feminist, lesbian, poet, mother, activist, essays; Lorde embodied and owned all of these self-identifying titles. Her belief in the power of language, of speaking out and confronting injustice rather than staying silent, woke me out of my own silence.

There is a magnitude of power in Lorde’s perfectly articulated words that speaks to the reader, and not simply due to the fact that many of the essays were written as speeches to be delivered in front of an audience. What is more important is what the book represents today in the world that we live in now – sexual assault, racism, rise of the far-right, slave trades, genocide, Trump, Brexit – Lorde’s work is essential reading not just for women of colour but for everyone. Your silence will not protect you. Words that ring scathingly true in times where silence is often complicity. Your silence will not protect you. And speaking your truths as women, black women, women of colour is survival, is revolutionary, is power.

The book is prefaced by Reni Eddo-Lodge, (Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race) and includes an Introduction by Sara Ahmed (Living a Feminist Life), who are both incredible and must-read authors and scholars, also.

Neale Howells

With the tail end of our hamburg show finishing at the beginning of 2017, and then with the first of two London fashion weeks with jayne pierson it was a full year… and of course being involved with Wales Arts Review‘s A.I.R was a great way to get things ofF my chest… but my chosen event was our solo show at the john martin gallery London in June 2017… when you prepare for a show this large it usually takes about three years… well for me it can… with large works, some 8ft x 36ft with a mixed medium i want and need them to be worth their wait… in amongst this you are also evolving so you are able to notice how the work can change… for instance at this show we have certain comic themes used in the works but which once they are out of my system the work seem to become less dependent on that and more explosive with jigsaw type outlines… i think that each piece becomes almost real in the sense that it has a right to exist … and how do this happen? well, its not just about throwing paint at a work… well, ok, it is but – it’s also about finding its character… the small parts are just as important as the large ones… just like you believe in cartoons when they are just drawings i want you to believe in these… we was very fortunate again to see the work well received and seen and hopefully we can push forward and bring the work onto the international stage where it can compete with its contemporaries… we are already looking forward to ART London 18 and the very important DUBAI art fair 2018… cross those fingers…

Kate North

My choice for highlight of 2017 is Rufus Mufasa’s debut album, Fur Coats from the Lions Den. This much-awaited album from the lioness lyricist is a powerful explosion. Download it, turn up your speakers and enjoy. Now.

Mufasa’s energetic hip-hop ensemble meshes blues, funk, soul and acoustic with a sense of urgent agency. With tracks in English and Welsh, her authoritative voice blasts flame through the dark. The album opens with ‘Coel Coeth’ (Ft. Robert Greig), setting what follows as part of the ancient coal lighting ritual. While definitely rooted in the present, tracks like ‘Daughters of Dylan’ acknowledge the Welsh traditions and legacies that inform this album. Highlights are the angry and sardonic ‘Skank it Out’ (Ft. Fearny Mac), with lines like ‘you’ve got so much baggage/you’re going to need a transit’ and the relentless delivery of ‘Gwastraff Amser’. The longest track on the album, ‘Leaf Fall’, is a crescendo showcasing the passion and also the persuasive magnitude of Mufasa’s voice. The surprise track has an old school brassy charge, making me play the whole album straight over again once it had ended. I’m going to be listening to this throughout the Christmas break and way into the beyond. I couldn’t make the official album launch in Swansea, so this is a plea to Rufus Mufasa. Please take Fur Coats on tour. Pretty please.

Mufasa’s energetic hip-hop ensemble meshes blues, funk, soul and acoustic with a sense of urgent agency. With tracks in English and Welsh, her authoritative voice blasts flame through the dark. The album opens with ‘Coel Coeth’ (Ft. Robert Greig), setting what follows as part of the ancient coal lighting ritual. While definitely rooted in the present, tracks like ‘Daughters of Dylan’ acknowledge the Welsh traditions and legacies that inform this album. Highlights are the angry and sardonic ‘Skank it Out’ (Ft. Fearny Mac), with lines like ‘you’ve got so much baggage/you’re going to need a transit’ and the relentless delivery of ‘Gwastraff Amser’. The longest track on the album, ‘Leaf Fall’, is a crescendo showcasing the passion and also the persuasive magnitude of Mufasa’s voice. The surprise track has an old school brassy charge, making me play the whole album straight over again once it had ended. I’m going to be listening to this throughout the Christmas break and way into the beyond. I couldn’t make the official album launch in Swansea, so this is a plea to Rufus Mufasa. Please take Fur Coats on tour. Pretty please.

Christoph Fischer

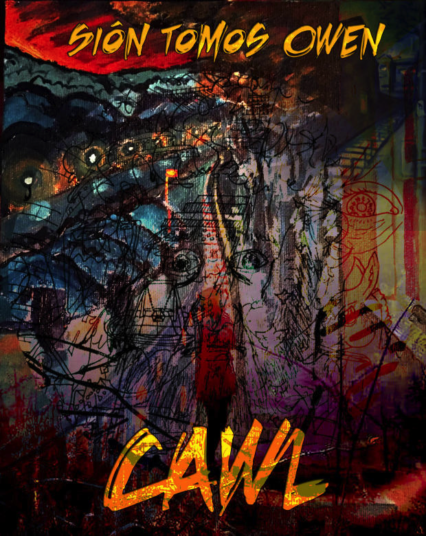

My highlights of 2017 were small but very memorable events. One was seeing Siôn Tomos Owen presenting his poetry, comic and short story collection CAWL at the Llandeilo Lit Fest.

Siôn has great stage charisma and CAWL is a very apt reflection on life in Rhondda, a county that has suffered from the end of coal mining and often feels like a forgotten piece of the country. He bemoans the harsh living conditions, the political situation, ignorance of people about Wales, the depressive economic situation and many other things. He does so, however, with a lot of good humour and in shape of satire, comics and appealing poetry, in both Welsh and English.

Siôn has great stage charisma and CAWL is a very apt reflection on life in Rhondda, a county that has suffered from the end of coal mining and often feels like a forgotten piece of the country. He bemoans the harsh living conditions, the political situation, ignorance of people about Wales, the depressive economic situation and many other things. He does so, however, with a lot of good humour and in shape of satire, comics and appealing poetry, in both Welsh and English.

While there is anger, there is also love and warmth as well as personal sharing of his perspective on life as a father. It is much more rounded than taglines about the collection may suggest. It is also very entertaining.

I equally really enjoyed listening to rugby mad poet and musician Pete Akinwumni, who recited his poems to an appreciative audience in Llandeilo. I’m not easily impressed by poetry but Akinwumni is an excellent performer and his poetry sounds effortless and smooth.

Good things come in three, and only weeks later did I have the pleasure of listening to poems from “Fox in the Yard” by Peter J. Jones, opening the newly established Llansteffan Lit Fest. Three artists to watch in 2018.

Adam Somerset

In October I caught an exhibition of paintings by David Cowdry, inspired by landscape, light & wildlife in the amazing Aberglasney Gardens. Cowdry creates stunning oil paintings in splendid colours, with a visual eye for art in landscape and nature and particular talent for incredible underwater images.

My best and least-best exhibitions of the year were small ones. I had a family invitation to Matisse in the Studio in the RA’s Sackler Rooms. The visitor numbers that were packed in were so great that the works were unseeable in full at any one time. Happily the close-by Burlington Arms was able to supply the solace and refreshment that eluded the art.

The National Museum in Cardiff in contrast is offering an exhibition that has a small fraction of the Academy’s advertising splash and dash. Bacon to Doig. Masterpieces from a Private Collection – which continues until end January 2018 – is just that. A single room contains nineteen canvases and eleven pieces of sculpture. The beautifully lit painters are Auerbach, Bacon, Freud, Nicholson; the sculptors Armitage, Hepworth, Kapoor. A Peter Doig is hung to the right of the entry door, its title “Untitled” and its year 2001/ 02. Two metres square in size its subject is a frozen lake from Doig’s time in Canada. A block of Le Corbusier flats in the distance provides perspective. Paint drips down the canvas in a simulacrum of ice. The canvas, which has been given a last pale wash, exudes frozenness. Its depth is considerable and its impact remarkable.

Peter Lord won, deservedly, his award of Book of the Year for The Tradition. I took a trip to Swansea to see the Evan Walters works in the ownership of the Glynn Vivian Gallery. After the gallery’s closure for two years BBC Wales had been on hand to report on the result. Its deeply misplaced review of the year’s arts failed to notice that the paintings most significant to Welsh culture were nowhere to be seen. Wales is let down by too many an arts manager who sets the pleasing of other arts professionals in priority over the interests of the citizenry.

Kevin McGrath

On being asked to nominate an outstanding artistic achievement for 2017, my initial response was that this year, more than any other, my choice should make reference to the times in which we live, and particularly, the fact that a proto-fascist had wormed his way into the White House. Among the first of New York’s artistic community to respond to Trump’s enthronement was Brooklyn’s psych-folk collective Woods. Jeremy Earl, the band’s singer and spiritual leader, cancelled his ensemble’s scheduled downtime and fast-tracked plans for a Lennonesque protest album that posed a fundamental question for each of us: ‘How can we love with this kind of hate?’

Ultimately, though, (and this may be how we all got ourselves into this jam in the first place), I opted for escapism over activism. Silent Forum, a Cardiff band that specialises in a claustrophobic, yet cinematic strain of Indie noir that can be traced back, via Editors, Interpol, Whipping Boy and Minimal Compact, to Manchester gloom merchants Joy Division, played a DIY gig in a box room in Cathay’s Youth and Community Centre last month that made me forget, at least for a precious 60 minutes, that the end of the world was nigh.

Led by the animated, enigmatic and compelling Richard Wiggins, part Ian Curtis, part Samuel Herring and part Marcel Marceau, the band tore through a set stuffed with new material like “Healer” and the heavily ironic “How I Faked the Moon Landing” (the combo’s former name in happier times), as well as the best tune of 2017, “Limbo”, which begins with an eerie discloser: ‘You may have noticed that I only write about you’, and ends with Wiggins intoning feverishly ‘never in love, no never in love’ over and over again as the music fractures around him. For now, Wiggins is the best-kept secret in Welsh pop. That should change in 2018.

Emily Garside

Angels in America ends part one with an Angel crash landing through a ceiling. In 2017 I feel like that Angel crashed into my life once again.

The production itself was everything a revival should be – a true re-working from the ground up. From the jaw dropping moment of the Angel’s arrival, to Brechtian stylings that were of such eloquent genius it showed a director with an understanding of the delicate ecology of Kushner’s writing. A production that in its performances defied both the assumptions of ‘star casting’ and re-wrote the interpretation of characters that previously seemed set in stone.

Elliott’s version of Angels was also the most hopeful version of this play, and the most hopeful piece of work I saw this year. Who would have thought that we’d need a play about Reganism and Roy Cohn in 2017 to give us hope? Or that a play about such a dark time for the LGBT community could in fact offer so much hope over 20 years on. In a time when politics and the state of the world has us rightly angry, these lessons from the past in Kushner’s play teach us to rage against the injustices, but that we still have an ethical obligation to hope as well. In 2017 we all needed that.

On a purely personal level, my play of the year could be nothing else. Some 14 or so years earlier they Angel first crashed into my life. A labour of love, that has shaped my life, across a decade, of 100, 000 words of PhD thesis and thousands more words in blog posts, message board comments, emails, tweets and arguments with wanker academics who obviously know better. All of that made that love of the play I once adored diminish slightly. In 2017, Marianne Elliott gave me that back.

Nigel Jarrett

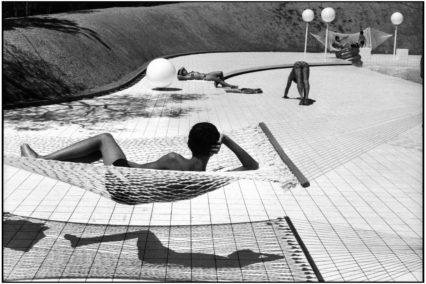

Photography still struggles as the less sophisticated sibling of fine art, mainly because it includes pictures of variable quality used as illustration in books, magazines, and newspapers and is thus compromised by usage. There’s also the widespread feeling that anything pictorial created by mechanical means extraneous to the direct, unmoderated mechanics of hand and eye is somehow deficient. Nowhere are comparisons more odious. What you get is what you see. The distinction is far more significant for the artist and photographer than for the viewer. Photography, though, is defined by the moment, however pictorial composition may be staged. These issues are raised again and again in the exhibition curated by Magnum photographer David Hurn at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, in which the work of many of the world’s best practitioners, including himself and intended mainly as reportage, aspire to the condition of art. These photographs discover in the moment its decisive merit, thus allowing them to meet the stasis of other forms of pictorial art on equal terms, while retaining the dynamics of the news story or magazine feature.

Hurn’s status, coupled with his long-established habit of ‘swapping’ prints with his celebrated photographer friends – Cartier-Bresson, Martin Parr, Bill Brandt, and many others – has resulted in an extraordinary collection, now gifted by him to the museum as the inauguration of a permanent photographic space. He was long associated with the Documentary Photography school at the former Newport College of Art, then famous for fine art but soon to offer degree courses in Graphic Design, a revolutionary discipline that allowed technology-driven picture-making to take over from easel-painting and led, in part, to the often facile offshoot of Conceptualism. That the photograph, once thought to make painting redundant, has never matched fine art’s plasticity, not least in its embrace of abstraction, is just one of the talking-points highlighted by this exhilarating show. These exhibits are explorations of the predicated figurative by some of the greatest names in photography. They represent the world seen through the artist’s eye, albeit with a mechanical means of recording and reproduction and with a deadline to meet, however distant.

Rhys Owain Williams

My highlight of 2017 is my hometown’s bid to become UK City of Culture. The campaign surrounding the bid (called ‘Swansea 2021’ from here on in) has done an excellent job of redefining residents’ definition of the word ‘culture’, and gained so much support in the process. Although it wasn’t hard to improve on the cutesy #CwtchTheBid hashtag that accompanied the city’s previous bid in 2013, Swansea 2021’s #SwanseaIsCulture seems to have really captured the imagination on social media. In addition to inviting variations that show culture is for everyone (e.g. #PoetryIsCulture, #FashionIsCulture, #KaraokeIsCulture), the hashtag has acted as a town crier for artists, events and venues around Swansea – proving that the bid is built on more than just skilful marketing.

Swansea will never escape the obscure comments of some Evening Post readers – who decide, for example, that the city can’t possibly win a culture bid because “…would you just look at the one-way system the council has implemented on the Kingsway!” I often wonder if Swansea is alone in this perpetual civic negativity, or if other towns and cities are burdened by it too. Thankfully the Swansea 2021 campaign has offered a much-needed counter argument, an outpouring of positivity about all the wonderful things going on in the city. I hope we can sustain this newfound readiness to ‘big up’ Swansea long after the bidding process is over and the bunting has been taken down. Even if the judges decide that Coventry, Paisley, Stoke-on-Trent or Sunderland are more cultured, there’s a lot of life left in #SwanseaIsCulture.

Permit me to scratch an itch though: a blot on the cultural landscape cultivated by Swansea 2021 appeared in November, when a bid event showcasing Swansea’s “exceptional poetry talent” included three poets (out of five) with no obvious links to the city. As talented as these out-of-towners may be, it’s bizarre that they were bussed in by the organisers when Sarah Coles, Christopher Cornwell, Nia Davies, Alan Kellermann, Natalie Ann Holborow and Richard James Jones were all on their doorstep – not to mention the lesser-known talent on the local open-mic circuit. With such a significant shadow already being cast from Cwmdonkin Drive, it’s a shame that the city’s contemporary poets were further obscured by the drafting of ringers. If Swansea is crowned City of Culture on 7th December, it’ll be criminal if the city’s poetic wealth isn’t celebrated more suitably in 2021.

Rhys Owain Williams is a writer and editor from Morriston, Swansea. He runs The Crunch multimedia poetry magazine.

Mark Blayney

Staging Richard III these days is as much about what you avoid as what you show. We don’t want to see Olivier’s ghost limping towards us, screwing his vowels to the sticking point. Hunch-backing is usually out, and how to avoid déjà vu as the title character addresses us head on at the start, letting us know how his winter of discontent is thawing?

The Richard Burton Company’s solution, in their production at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, was to make Richard a soldier back from Afghanistan, his sociopathic qualities formed on the desert battlefields and his strapped-up leg an injury gained in life, not a deformity from birth. Sam John’s Richard was playful – murdering while he smiles, to quote a line that was cut from the ingenious and not too reverent production. We got a savage and sexy king, pumped up with lust for the crown. And by lifting scenes from the end of the Henry VI trilogy, the play could open with violence rather than well-trodden soliloquy.

Hannah Page’s white, glowing, twin-level set was used shrewdly, with back-lit ghosts oozing through the walls during Richard’s pre-battle nightmare. This was a glossy, expensive-looking, visual treat of a performance, immaculately performed by its third year student cast and vivid in its execution (and executions). There were one or two misfires – Richard starting ‘To be or not to be’ and then shaking his head as if remembering he was in the wrong play might have seemed funny in rehearsal but the play didn’t need it; the audience was rapt. But it was clear where these moments were coming from – a fizzing, energetic and thoughtful cast working with a director, Joe Murphy, who knew how to coax fine performances from them. For this number of reasons, RWCMD’s Richard III hacks its way through some fierce competition to become my cultural highlight of 2017.

Mark Blayney is a Hay Festival Writer at Work and a Wales Media Awards winner 2017.