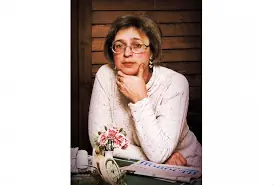

Notes of Solidarity is a new daily series of mini-essays, poems, and reflections on the Russian war on Ukraine by some of Wales’s leading literary figures. Here, writer and broadcaster Horatio Clare writes on the remarkable Anna Politkovskaya, a Russian journalist, and human rights activist who was murdered by order of Vladimir Putin in 2006.

Everything you might want to know, if you would understand the true nature of the monster you now face, has already been meticulously researched, searingly written and published – years ago. You can and should buy the books right now. They will change you. Her name was Anna Politkovskaya and she was a beautiful soul; the kind of soul, I imagine, who stays God’s hand, when God is tempted to end his chaotic experiment with humanity. He looks down at us and thinks, ‘But some of them do turn out like Anna Politkovskaya. Maybe I’ll give them another month…’

Vladimir Putin had her killed, of course, in 2006. Gunned down in her apartment. Shot in the back. When asked about her, in a press conference, Vladimir said, ‘Journalists should know, as experts do, that her influence on political life in Russia was extremely insignificant.’ Every word of that was a lie, as every Russian who heard it knew, which leaves us and God only one task, really: to prove that Anna was right about humans and the world, and Vladimir Putin – a name like Adolf Hitler, destined for the sickbag of history – is wrong.

Vladimir had her poisoned in 2002. She was on her way to Beslan to act as a mediator in the siege of a school. Vladimir revealed he would sooner her see her dead than have her end the siege. She survived. There were at least nine attempts on her life.

Her colleague on the newspaper Novaya Gazeta, Vyacheslav Izmailov, said, ‘Frontline soldiers do not usually go into battle so often and survive.’ Ismailov, ex-military, and a negotiator who had himself freed hostages in Chechnya, did not exaggerate.

Anna would not quit: she was beaten, constantly threatened and harassed, arrested, tortured, tried, mock-executed – she would not quit . She had a US passport but she would not spend more than a few weeks outside Russia. Everyone talked to her, even the generals and the FSB. She was a light, and she set the standard in human integrity and bravery. She went into the heart of hell in Grozny, where she was threatened with rape and subjected to mock execution. She interviewed Ramzan Kadyrov. Of course she did. Ramzan is Putin’s id, a psychopathic thug, Putin without the suit and the brains it takes to lie. His murderers are in Ukraine now – they call him Putin’s son.

Reading Anna’s interview with him will tell you how brave you are. He kept her waiting for six hours plus, in a room, where, she noted, for some reason they had not removed the price tags from the furniture. It’s the Russian Joan Didion going to meet Himmler. He told her she should be shot. She described him as the Chechen Stalin. When it was done she was sure he would have her shot in the back. The bullets waited. She published the piece, allowing Ramzan to show himself in his own words as thick, evil, utterly Putin’s creature, deadly. She published so much and she must have known Vladimir would kill her for it.

Anna Politkovskaya’s books include Putin’s Russia and A Russian Diary. Read them. She identified what she called the ‘Chechenisation’ of Russian society: if a country is lied to sufficiently, made complicit in brutality sufficiently, corrupted sufficiently, it becomes coarsened, biddable, brutal. I have often thought of this, watching the effects of Trump, Farage and and Patel on their supporters.

Anna was the best of us, the best of Russia, the best of journalism and humanity. In her books she left us a complete guide to the monster you now face. She wrote: ‘[It] is we who are responsible for Putin’s policies … [s]ociety has shown limitless apathy … [a]s the Chekists have become entrenched in power, we have let them see our fear, and thereby have only intensified their urge to treat us like cattle. The KGB respects only the strong. The weak it devours. We of all people ought to know that.’

At the time that ‘we’ referred to the ordinary Russian people, but history has seen fit to make us all the ordinary Russian people. When a journalist is brave enough, skilled enough and determined enough, their work tells you as much about tomorrow as it does about today. Anna wrote, in an essay called Am I Afraid : “People often tell me that I am a pessimist, that I don’t believe in the strength of the Russian people, that I am obsessive in my opposition to Putin and see nothing beyond that”.

Her last sentence reads: “If anybody thinks they can take comfort from the ‘optimistic’ forecast, let them do so. It is certainly the easier way, but it is the death sentence for our grandchildren.”

Those grandchildren are currently killing and being killed in Ukraine.

When Vladimir murdered Anna Politkovskaya I went to the Russian Embassy in London to join a vigil for her. I was late leaving the office; when I arrived, there was almost no one left; just flowers and candles and wax like a dragon’s tears on the pavement. As it happens, my grandmother was Russian, from Moscow, and her mother was from Brest-Litovsk in Belarus. They fled the country, made stateless by the Red terror organised by Putin’s professional forbears. I learned Russian; I love Russian culture, especially her literature, jokes and music, and am drawn to those of its people I have met. Back then, Anna’s murder made me furious and distraught with a helpless indignant rage, as a reader, as a journalist, as a part Russian.

But now I think, strangely perhaps, that all will be well. It is no longer just Russians and journalists and their victims who know that Vladimir and Ramzan are evil in the raw. It is all of us. And we are many, and they are few, and we will win. And the day we do we will raise a toast to Anna Politkovskaya, and cheer her name, and we will damn Ramzan and Valdimir’s memories into the eternal pits of hell that await them. We are many. They are few. We will win.

For more information on the Russia-Ukraine war, including ways you can help, please click here.

You can follow all contributions to Notes of Solidarity from Wales Arts Review here.