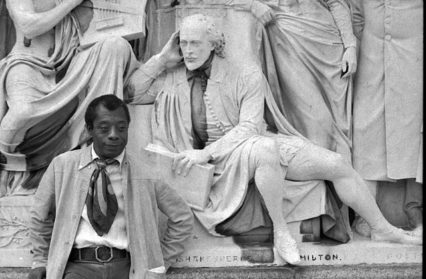

Mustafa Hameed reviews the brilliant new documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, from Raoul Peck, who took the unfinished script of James Baldwin to create a profound and coruscating direction of race issues in America.

When an English filmmaker named Dick Fontaine came to Baldwin in Sain-Paul-de-Vence with a documentary film script that would attempt a visual inventory of the author’s life, literary works and ideas, Baldwin responded with outrage at what was presented before him. “I am not going to let you define me!” he shouted during the conflict.

According to Baldwin’s biographer, David Leeming, Baldwin felt violated, misunderstood even “distorted” by Fontain’s depiction. This was an archetypal Baldwin outburst. Fears of being misrepresented married with a sense of insecurity of who he was – Black, homosexual, writer – such existential uncertainties forced Baldwin to occupy the cracks of any group or society he found himself in. It was this outsider status which essentially turned Baldwin into the unique writer-cum-activist he would eventually become. Later, however, Baldwin was to permit Fontaine to trail him around in a political sojourn beginning in the American south in what eventually became I Heard It Through the Grapevine. In it an aging and broody Baldwin revisits old friends and hangouts which had been significant turning points for him personally during the tumultuous events of the civil rights movement. “Medgar, Martin, Malcolm” we hear Baldwin say “all dead. All younger than me. But there was another roll-call of people who did not die but whose lives were smashed on the freedom road”.

That documentary film was originally intended to bear the title Remember This House, a title Baldwin had chosen for a book he had been working on exploring the civil rights movement through the personalities of its three slain, prophetic stalwarts – Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. All had been callously assassinated as Baldwin stood by helplessly absorbing the quick succession grief, consecutively mourning each loss as if it was a member of his own family. Baldwin was aware that these murders were merely the upshot of an historical hatred that had been long trapped and hidden, nurtured even, in the very heart and fabric of American society and in the very soul of its unreflecting history. The deaths had left an entire people shell-shocked, for all three men embodied the distilled spirit of defiance and sacrifice of a Black nation within a nation who had been systematically violated for nearly 400 years. Hope itself, it seemed, had been murdered.

It would not be unreasonable to say that Baldwin’s contribution to the debates around civil rights and African-American identity suffered an unconscious omission during the years after his death, eclipsed as they were by the formidable legacies of Malcolm and King both of whom became posthumous icons of African-American identity.

In I Am Not Your Negro, Haitian director Raoul Peck attempts to redeem Baldwin’s fiery legacy, resurrecting his voice and vision once again in a faithful attempt to complete the work Baldwin had began in Remember This House. The result is an enthralling documentary of a towering “Black” intellectual who finally manages to liberate himself and his ideas from the historical shadows of his contemporaries. Baldwin emerges as a powerful and precocious spirit that seems to outwit history, passionately schooling the audience about the complex issue that is race in America.

“I want these three lives to bang against and reveal each other” we are told by Baldwin whose narrative voice is carried brilliantly by Samuel L. Jackson. For Baldwin this “journey” into the past is one which would fill his soul with a tremendous degree of trepidation. Baldwin’s own voice hammers against theirs revealing aspects about himself he still had yet to confront or discover.

There is guilt in Baldwin’s voice. “Everyone else was paying their dues and it was time I went home and paid mine” Baldwin says. Such guilt emanated from his own feelings of abandoning his role as a courageous “witness” and participant in the cause. Baldwin had spent a considerable amount of time in Paris in order to give himself clear stab at becoming a writer that only geographical distance could. This decision to emigrate was precipitated by an infamous incident in an American diner where, upon being refused service, Baldwin violently hurled a glass at the White waitress behind the counter causing the mirror glass behind her to shatter. No one was more disturbed by this violent outburst than Baldwin himself. He knew then that he simply had to leave America now or die with the hatred, rage and feelings of self-loathing that American society was engendering in young Black men like him up and down the country.

Years later, while passing a kiosk in Paris, Baldwin would come across the image of a young black fifteen-year-old girl named Dorothy Counts on her first day at an American university. In I Am Not Your Negro we are confronted by images of her as she is heckled and abused by a sea of White racists as she makes her lonely way towards the halls of learning. Baldwin tells us that he was no longer able to justify his absence or stand by while young Black Americans like Dorothy were “being reviled and spat on by the mob…with history, jeering, at her back”. This is captured movingly by Peck, revealing Baldwin’s inner anguish, turmoil and shame as well as the moral depravity of America itself. Baldwin needed to go back not out of guilt per se but out of a sense of personal moral responsibility.

The film does not shy away from tackling the tentative and treacherous terrain of race in contemporary America which oftentimes feels like an eternally inscrutable ticking time bomb. With the help of Baldwin, whose medley of narratives is continuously foreboding, Peck seems to be telling us that, when it comes to the issue of race, American society is forever holding its breath. Peck powerfully weaves images of the Black Lives Matter movement into the documentary as Baldwin reflects on the historical catalogue of physical and psychological brutality, a brutality that is made even more frightening by what Baldwin sees as the moral apathy of American society which was slowly turning into a society comprised of “moral monsters”.

Peck neatly brings Baldwin’s voice to bear on an ostensible “Post-Racial” America where myths and misrepresentations of what it means to be Black (black sexuality, for example) continue to proliferate even post-Obama. Post-Racial America suffers from a cognitive dissonance where, as Baldwin tells us, “public stances” and “private lives” hardly ever enter into an honest dialogue with one another. Only on regrettable occasions of overt racial violence followed by institutionalised impunity for the perpetrators does American society shake its head from out of the clouds.

Peck also segues into the American dream – a life of unbridled material comfort and smug sense of security with Baldwin warning us that such ease of living comes at a great and terrible cost. For Baldwin America is a nation addicted to the “self-perpetuating fantasy of American life”. A fantasy which is only made possible by closing one’s eyes to the vicious underbelly of its past/present injustices thus solidifying a dangerous mindset that only weakens its ability to deal with the world as it is.

The public intellectualism of Baldwin is also showcased as we hear Baldwin deftly switch from subjects such as the psychology of the subjugated masses to representations of Blackness in Hollywood films. The latter is reminiscent of Edward Said’s book Orientalism and will forever change the way you watch a film starring Sidney Poitier or what you think you knew about the singer, actor and social activist Harry Belafonte. Baldwin, like Said, is aware that no form of representation is innocent since the reproduction of such representations or discourses cannot be divorced from power and the reproduction of dominant structures.

Indeed, Peck does not shy away from making the film academic, recognising that in an age of faddish intersectionality and fervent politics of identity with complicated global dimensions, topics such as race can no longer be reduced to the inflexible binaries of Black/White and that to do so would be to the social and cultural detriment of all.

In I Am Not Your Negro Baldwin successfully emerges as that rare breed of cultural critic who communicate to us in simple terms the urgency of how we are all connected in one way or another and that our private lives can rarely, if hardly ever, be separated from our public personas. “If you capable of loving one person” Baldwin would often say, “you are capable of loving all persons”.

In this way Peck is true to the spirit of Baldwin’s prose where he oftentimes, in a single paragraph, achieves the mesmerising feat of getting to the heart of the domestic experience of African-American life while forcing it to beautifully resound with the universal and timeless aspects of American idealism, something the neo-Pragmatist philosopher Cornel West would describe as a “romantic project in which a paradise, a land of dreams, is fanned and fueled with a religion of vast possibility,”. America is then for West, as it was for Baldwin, a “fragile experiment-precious yet precarious” with the overcoming of the “race problem” as one of its most challenging hurdles. Peck reminds us that there is not a single sphere of human relations that can be harmed without it impacting someone or something else. “The story of the Negro in America,” Baldwin tells us, “is the story of America”.

Footage of Baldwin debating university professors and other figures as well as various one-to-one interviews demonstrate just how much of a brilliant orator he was. One is left with the feeling that one could listen to the man forever – his speech is measured, rhythmical and poetically timeless as anyone of his brilliant novels or plays. While watching him, one can almost feel the cogs of his philosophical and literary mine turning as the audience waits with anticipation for his next pithy statement.

Peck’s documentary does, however, leave a lot to be desired. While we learn plenty about James Baldwin the activist, we learn little about James Baldwin the writer, or about the personal Baldwin for that matter. Perhaps to do justice to Baldwin the writer, one must read his works. Instead, Peck has made a consciously and selective decision to make sure Baldwin speaks to the contemporary feelings of political and social alienation felt by the most vulnerable and downtrodden stratum of American society.

Peck seems to be bent on impressing the desire Baldwin had to create a nation of introspective White and Black Americans. We come to learn that Medgar, Malcolm and Martin were men who Baldwin certainly held in the highest regard. All were men he had a deep sense of brotherly love and affection for. But we also learn that such affection was equally complicated by the fact that, for Baldwin, each of these leaders represented a distinct strand, methodology and approach he would never commit to (people often forget that Malcolm X derided King’s March on Washington as the “Farce on Washington”).

Baldwin was, for example, far removed from the reactionary violence and “racism” – as he saw it – of Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam or Black Panthers but understood such movements to be the inevitable by-product of American history. He felt disconnected from the naive pacifism of King whose Biblically inspired turn-the-other-cheek love philosophy had reduced too many into sacrificial lambs, leading them to the political slaughterhouse. Softer organisations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) seemed an unlikely political home for Baldwin riddled, as he saw it, with its class distinctions. Some of King’s entourage were also hesitant to affiliate themselves with Baldwin because they feared speculations around his sexuality might damage the image of the movement. Peck’s film could have further benefited into making forays into such differences.

Having said this, Peck does show how Baldwin was forced (or forced himself) into the watchtower of history as an omnipresent, prophetic observer and wary critic of the emerging ideas of race during Civil Right’s America. He was a man who had such an acute sense of history, which he said could never be separated from the present, that he almost occupied a space outside of it. He knew that when it came to understanding the sensitive issue of subjugation created by the then unassailable idea of White supremacy one had to ask more questions than one could possibly answer and that the Medgars, Martins and Malcolms of his world, rightly or wrongly, were simply not digging deep enough. As Leeming informs us that through a letter Baldwin wrote to his brother, David, that he felt constantly “estranged” from both “Black and White intellectuals” and their approaches because they were “all heat and no light”. Surely between Malcolm and King there had to exist a third way?

Peck manages to elevate Baldwin above the towering historical edifices of Malcolm and Martin who for far too long had cast their historical shadows over him thereby keeping his ideas in the dark. Baldwin is offered as an alternative forgotten hero whose ideas seem ever salient in the contemporary moment, more so than any of his contemporaries. As Peck demonstrates, Baldwin’s mission was to test the “moral commitment” of White Americans especially those in a position of power and influence such as the Kennedy brothers who seemed to support equal rights in theory only.

Watching the film made me think of Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. The protagonist, David, tells us that “Nothing is more unbearable, once one has it, than freedom”. Vacant freedom was not the goal for Baldwin. It was the quality or morality of freedom that truly made freedom something worth striving for. The work of freedom began once one possessed it. White Americans had themselves proved this. Just look what they had done with their freedom, using it as a license to deprive another people of theirs. The question they had to ask themselves is why they needed to do this. “Why they needed the nigger in the first place”. Such a question was important for it would essentially yield the answer as to why we as human beings felt compelled to subjugate one another at all.

In a lecture to a group of young African-Americans Baldwin would tell them that they were also capable of treating people the way they had been treated. For Baldwin freedom could not be separated from the idea of responsibility, a personal sense of morality and facing up to the terrible facts of life. I Am Not Your Negro is a film directed at White America but in a sense a statement directed at Black America too and America generally. Baldwin refused to uncritically step in to the straitjacket of the political status quo, the fads of racial identity politics or affiliating himself with any particular ideology. He understood that the problem of race was a problem that could only be resolved if everyone came to the table. The goal was always had be to get to the roots of hatred itself.

If the Civil Rights movement with all its extraordinary heroes was written as a novel, Baldwin would be the perfect narrative voice to lead us through the whole saga. With his incisive literary eye, sense of history and (reflective) passion for the struggle, he would no doubt penetrate the inner life of the movement as well as its personalities while relating it more broadly to the idea of America itself. In I Am Not Your Negro Peck does a faithful job in redeeming Baldwin, positioning him as that courageous “witness” whom all – barring himself – knew he would always be.