Francesca Donovan has a chat with Richard Higlett, one of the driving forces behind Cardiff Contemporary.

It is just over a week since Cardiff Contemporary 2014 closed its metaphorical doors. As a member of the team whose collective breathless hard-work has been the foundation of the festival’s success, you would think the forty-seven-year-old Warwick-born artist would be left with time on his hands. You would be wrong.

Higlett can now focus on his personal creative output. ‘At base level I class myself as a practising artist,’ he said, although Richard added, ‘I mean, I don’t like to think of myself as an artist; I just make things and other people decide that.’

Richard ‘came to art late in life’. After giving up a career in carework he completed his MA in Fine Art at Cardiff Metropolitan University (formerly UWIC) in 1999.

‘I’d always made art but I went into full-time education when I was 25. I had been a stress engineer with an office, car and £12,000 a year. It was 1989 and that was a lot of money but it was like “Wow, this doesn’t matter, what do I really want to do?”’

Higlett’s artistic practise itself is a very intriguing notion. Richard said, ‘I have an alter ego called Wally French who is my sort of commercial wing. He makes work – I talk about him in the third person – that is like an alternative pathway of twentieth century art. It relates to twentieth century conceptual art but its done in a very Outsider Art, Folk Art way. He’s quite popular.’

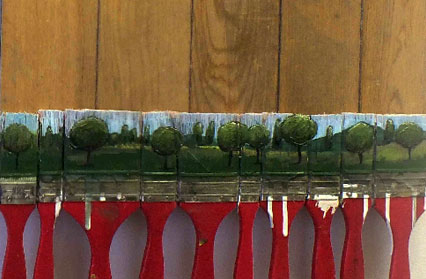

‘The idea of Wally is that he’s a suburban landscape painter. The back of his house in the 1940s used to be trees and fields and he’s now surrounded by housing estates. So he paints on things around his house to reclaim the landscape. Landscapes on frying pans, Mills and Boon paperback novel front covers, paintbrushes, knife handles, there’s a series of suitcases – I did objects in suitcases – so it’s that idea of wanting to reclaim the objects of your circumstance.’

Wally French said, ‘Some people say I’m a fictional person but that depends on whether you believe in fact or fiction. Some people say I’m an outsider but that’s dependent on knowing what is inside.’

Higlett also opened up about some of the greater issues in the art sphere that affect practising artists, such as centralisation. When asked, Richard explained the localisation and density in numbers of major commercial artists in London by saying, ‘There is a very particular type of artist who lives in Cardiff. We’re all of a similar sense of aspiration; a soft ambition so to speak. I don’t think there are many artists in Cardiff who are very ruthlessly ambitious.’

Alongside Richard’s successful art practise, he is an influential figure within Cardiff culture. He started ArtCardiff in 2007 and in conjunction with the project, initiated Cardiff Open Studios. That year, Higlett also co-founded Mermaid and Monster. He went on to co-found Goat Major Projects in 2012.

Richard begins these initiatives because he sees gaps in the Cardiff’s art scene: ‘What’s missing, you know? Two, maybe three, commercial galleries the size of Bay Arts that could sell contemporary art? Now that Tactile Bosch has gone what opportunities are there for artists leaving college? That’s missing. What’s the relationship between the college and the indigenous art scene? Very poor. There isn’t a great deal of crossover. That’s lacking. It’s about what’s missing and what you can do to try and fill those gaps.’

Richard was a central figure in the group of artists that came together to initiate Cardiff Contemporary in 2005. ‘The point of Cardiff Contemporary was to create a situation in which art is everyday and has potential for things that you wouldn’t necessarily see normally. The agenda this year was to embed the festival in the psyche of the local authority and to get them to realise the benefits of free access to the visual arts. [It gives] the opportunity for people to think creatively as part of a general plan to make Cardiff better.’

No wonder Cardiff Contemporary has become part of the annual cultural furniture of the city. It proved popular with both the arts community and the wider spread of residents and visitors. However, when asked about how the festival was executed Higlett stated, ‘If anything there was too much work, too much going on, too many things to see. But it’s all a learning curve.’

Regardless, Cardiff Contemporary has an economic payoff, as Richard explained:

‘For a relatively small Arts Council Wales investment, compared to other costly events in the city – like fireworks and hanging baskets – you get something that had a massive impact on tourism and animated a community.’

Funding is guaranteed until 2017 and planning has commenced for #CC2015. ‘Cardiff Contemporary has a ripple effect,’ Richard said. ‘It’s a very small stone but it’s a very dense stone. The weight of it positively affects the way the city is perceived.’

Richard works regularly at Chapter in Canton and also has a residency studio there. If you wish to find out more about any of the issues raised in this article, he is available to speak to in person, in his role as a live gallery invigilator.

He welcomes conversation in this context, saying, ‘I work here as a live guide invigilator because I like it and it’s regular money. It’s nice just to watch people. It’s useful for understanding how people negotiate work and how you can curate and place works, as an artist. It’s good to find the hidden narrative in how people negotiate space, really.’

You can also visit his website and blog to view some of his artwork or tweet him.

For a closer look at some of his projects and initiatives he is involved in, follow the links below:

Goat Major Projects

Artes Mundi

Mermaid and Monster

Arts Council of Wales (Consultant)

Cardiff Open Studios

Image courtesy of Richard Higlett – paintings on Brushes by Walter Percy French

A previous version of this article mistakenly gave the impression that Richard Higlett was the sole organiser and founder of Cardiff Contemporary. We would like to make clear, as would Richard, that this impression was not intended, and corrections have been made to make it clear that although Richard’s role is central to the festival, he is part of a wider team, each of whom also have vital roles.