Satterday Shaw reflects on the work of artist Meic Watts, who works in slate, stone and time-based photography. Here, Shaw talks to Watts about the inspiration behind his work and his current exhibition in Oriel Môn gallery, a collaboration with fellow artist, Bill Swann.

Slate Feathers

‘The work is about the environment, our human relationship to the natural environment and how we’re losing touch with it.’ Sculptor Meic Watts is speaking about both of the disparate strands of his work: sculptures fixed in slate and stone; and time-based, experimental pieces.

I ask Watts about his inspirations after seeing a show at Oriel Môn (Sept-Nov 2022) in Llangefni, which displays his sculpture alongside that of glass artist Bill Swann, including some collaborations. Watt’s large pieces such as Adain Llech/Slate Wing (2022), 159 cm in length, make me wonder how such a brittle, intransigent material can conjure up the freedom of flight.

‘I like the idea of making slate appear as thought it has no weight,’ confirms Watts.

In Adain Dwylo/Wing of Hands (2022) another wing, formed of hands, lifts dear faces including those of Meic’s nain and taid. Resembling a memorial stone, the relief carving encapsulates the way our actions join with those of our ancestors to create a legacy for our descendants.

A shaman’s cloak (Mantell yr Offeiriad/Priest’s Cloak 2022), 150 cm high, composed of small individual slate feathers, grabs my imagination even before Watts expands on its significance. ‘The human being has to wear this heavy cloak in atonement for our destruction of other nature,’ as though the priest were wearing the slate waste tips translated into feathers; the shaman will find their way back to a kinder relationship with the rest of life. Watts intends to make another version of the cloak that may be worn. Or possibly several versions: a cloak of slate feathers carved with poems, for example.

Cynefin

During lockdown, Watts had time to see individual trees and ferns unfurling with the spring, and to photograph the daily changes.

‘I met young hares that had never come across humans, and weren’t frightened,’ he says. The birds weren’t frightened; it seemed like a new Eden, a chance for reconciliation between humans and nature.

Watts has acquired the skills to make the kind of work he’s been envisaging since his college days. Educated in North Wales, he set off to Norwich School of Art to be a painter. But he felt so homesick for Eryri that he would carry lumps of his homeland stone back with him after the vacations. Cynefin (belonging) ‘is your home patch; sheep who’ve got to know a piece of land where they’ve grazed will find it hard to adjust if they get moved.’ He began to explore ways of relating to animals and birds, investigating their anatomy, their behaviour and their symbolism in spirituality; along with a fascination with traditional crafts and their connection to the landscape: paper-making, basket-weaving, wood carving. He started to make ephemeral pieces in the landscape at this time.

Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), with his interest in materials as symbolism and art as shamanism, was a major influence, as were land artists Richard Long, Hamish Fulton and Andy Goldsworthy. Watts also took inspiration from the community-environment charity Common Ground, formed in 1983. Watts remembers a lecturer in Norwich, Tony Carter (1943-2016) for his transformation of objects and love of nature’s healing powers. Another memory values the exquisite mediaeval carvings in the vaulted stone roof of Norwich Cathedral, among them a Noah’s Ark and a mermaid.

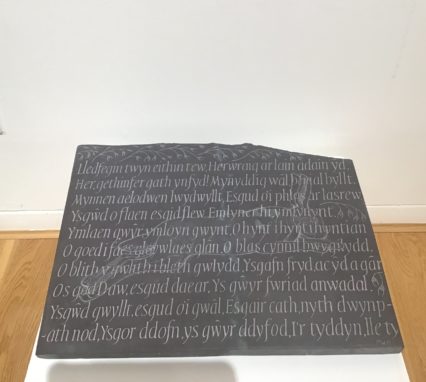

During a vacation, Watts began an association with sculptor Jonah Jones (1919-2004), who lived in the next Welsh village. During an apprenticeship with Jones, after college, Watts learned lettercutting in stone. He uses lettering in recent relief carvings such as ‘Ysgyfarnog Dafydd ap Gwilym/Dafydd ap Gwilym’s Hare (2021-22), an Ogwen-slate panel that shows part of the poem ‘Love compared to a Hare’. Watts enjoyed the discipline of learning the craft, but felt a conflict between his ephemeral pieces and those set in stone.

He exhibited with Jones and another slate sculptor, Howard Bowcott, and began to contribute to public art commissions. He appreciated the support of Claire Langdown and David Nash from Blaenau Ffestiniog. Since those days he’s exhibited in the UK and Europe, run workshops for schoolchildren and carried out commissions, working in granite, limestone and sandstone as well as slate.

Craft and Art

Slate has contributed to the culture and economy of North Wales for centuries. Watts tells me it’s a difficult material to work because it’s formed in layers, both rigid and fragile. But it’s part of the place; it belongs. Quarrymen who lived in barracks would carve pieces during the evenings to take home as gifts: mantelpieces or house names; or they would push the limitations of the material to make an inkstand or a fan. Of course, many quarries have closed and traditions are disappearing.

But there’s a resurgence in the creative and skilled use of slate. Watts mentions a roofing company, Llechan Lân, who use roof tiles to compose large images to adorn local buildings: a heron or an osprey, for example.

‘What’s the difference between art and craft?’ I ask.

‘There’s no difference between an artist and a craft maker,’ Watts replies.

I’ve seen him described as a traditional sculptor (on the internet, in blurbs for an exhibition), but this summary misses out the powerful imagination of series such as Cyllell y Gwynt/Wind Knife (2022), where an aluminium knife transforms into a feather. The description certainly overlooks Watts’ time-based pieces, many documented over years.

Rivers of Light, Mountain Shadows

The other strand in Watts’ body of work is his practice of photographing ephemeral and enduring elements of land and water. In 1992, for example, Watts contributed to Journeys, a Southern Arts touring exhibition. His photos divulged the courses of rivers or estuaries by using a long exposure to shoot paper boats carrying candles along the currents. The prints elicit wonder not only at the magic of light on the stream but also at the patience and skill required to produce them.

Our chat about rivers helps me make a satisfying connection between Watts’ stone sculptures and his time-based work when he informs me that a friend told him that slate is formed from alluvial deposits in estuaries.

‘All slate?’ I ask.

‘All slate,’ he affirms. ‘In fact it’s not true, but estuaries do carry the clays that form alluvial deposits which get transformed into slate by pressure.’

More recently, Watts has been documenting how the river course has changed in the Dwyryd estuary. And climbing to the summit of Yr Eifl at every solstice and equinox to record the shadow cast by the mountain.

‘At Midsummer, the shadow stretches seventeen miles across the bay to Barmouth.’

Watts would like to complete a piece that uses the voices of local people to name all the fields and places crossed by the shadow. Along with the diversity of animals, birds, plants and insects, human connections with the land that include naming can be lost.

Aspirations

Watts wants to continue to produce work inspired by connections with nature, by the magic of hares, of flight, of naming, of rivers changing their courses and mountain-shadows that reach for miles. He’s hoping that if funding bodies see the depth of work he’s produced purely through sales and commissions, they may be willing to support him to complete the ambitious pieces he’s envisaged. I hope to see his work in the permanent collections of the Amgueddfa LLechi Cymru/ National Slate Museum and the Amgueddfa Genedlaethol.

Bill Swann and Meic Watts’ exhibition is on show at Oriel Môn until 6th November. You can find out more about the work of Meic Watts here.

Satterday Shaw is a writer, mother and anti-racist, published in Cree: The Rhys Davies Short Story Award Anthology, Mslexia, The London Magazine, Wasafiri, Michigan Feminist Studies, and other magazines and anthologies. You can find her on Twitter here.