‘There are certain exhibitions that simply astonish and mesmerise the viewer – some people are affected in this way by Rothko’s paintings and stand weeping in front of them for hours at a time. I vividly remember having a similar feeling when I saw Shani Rhys James’ exhibition ‘Blood Ties’ at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea in the early 90s. I can feel myself walking into the gallery space and stopping – seemingly bathed in rich red light as I was confronted by the figures in the pictures. I looked at them and they looked right back. These are works which need to be seen in the flesh.’ Jo Mazelis

1. Art student at Saint Martins (1975)

Jo Mazelis: In this photograph, Shani you are shown in the act of painting while a student in London. You look very young and small; the picture seems to dwarf you. Knowing you had come to London from Australia how strange was that experience? Art College itself being a slightly curious institution especially perhaps in the early seventies. Was it alienating for you or did you feel you had come home, both to painting and the UK? Is the photo a self portrait?

Shani Rhys James: I felt I had come home. I had done a foundation course in Loughborough and was desperate to get back to London where my parents lived. We lived in Camden town, so when I was at Loughborough I used to go back to Camden market and take black and white photos with my Zenith camera. The most extraordinary faces, one character was Alan Bennett’s old lady, the subject of his story The Lady in the Van. She was a tall imposing woman dressed in old clothes, with men’s shoes, I took photos of her writing tracts on the pavement. Beside her was a long stick, she started to attack me with this stick, I kept on photographing her, I have those photos. Gnarled old men with bowler hats dressed in cast off gentrified clothes standing outside a second-hand clothes stall, one looked like an old ex-boxer with a pugilist nose. I would stay all day photographing these characters. The photograph above was me in the third year at Saint Martins, London. The painting is finished and turned on its side. It is figures, faces swirling, passed in London. I was thinking of those previous photographs I had done of London streets. I would pin unstretched canvas on the wall or on the floor and the paint marks would direct the painting; the faces, the figures. I was also reading T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland and doing my third year thesis on Samuel Beckett, so it was the vibe of London, grimness of London streets, people, life. I was just as ambitious about scale and subject matter as I am now, my appearance belies the inner me. Saint Martins was fantastic. It was in the centre of London, Soho was around the corner, there was a freedom, the tutors were all practicing artists, mostly abstract. It was contagious. It freed one up, it was about colour, marks, freedom.

2. Head No. 1 (2003)

You have painted a considerable number of self portraits where you examine your face in close-cropped, paint-laden detail. These are not or don’t seem to be true representations, certainly the use of so much red is unnatural, and while the pictures broadly look like you it is also evidently not quite you. It is as if you are searching for something you can’t quite find, something beneath the surface of the almost flayed looking skin. Or perhaps these represent the artist alone in her studio who finds herself to be a convenient model?

Yes, all this is true. These are simply extensions of the same thing as I did at Saint Martins, The heads are abstract in many ways, they are about paint, colour, marks and they come together as a head, a landscape, seen in parts with a hand held mirror. It is not literal, it is not a self portrait as such, it is a way to study light falling on a 3D object, a head, and interpreting that as colour, and form and in that process it reaches something intense as it is focussed on one element of the figure, the head.

3. Bed and Wallpaper (2003)

Your work seems to return again and again to autobiographical subject matter that has been re-staged for dramatic effect. In this picture , set against a deep red wallpaper, a small child (you?) stands behind a puppet theatre looking wistful as if she were waiting for something; an audience? A playmate? Her mother? Or even, if the child is you, the adult self who has created this picture? I understand you were a child actress while you were in Australia, does the toy theatre represent that experience in any way?

I wasn’t really a child actress, I just happened to be asked to be in a film before I left Australia, a film I never saw until I was in my thirties. I think there are some personal experiences we have that can often be relived because of their impact on our lives if they are triggered- as if they are etched into us like a computer programme. This experience was not touched on as a child, or dwelled on at all until I came to Wales and then returned to Australia to meet my father for the first time. I hadn’t seen him since the age of two. I must have yearned for this meeting as I changed my name from Shani Money to Shani Rhys James in the third year at Saint Martins – his name, therefore taking on a Welsh identity in a sense. My mother had moved to Wales to be self-sufficient – one of those John Seymour followers, leaving me in a squat in London. (This squat was civilized and beautiful, not what it seems.) So I was searching for identity and it was as if a button was turned on inside me and made me feel such intense emotion for this father that it woke me up to face the experience of leaving Australia, what that meant, leaving all this family and my nanna who I had never seen again, also my aunt and step-father, all dead. Then suddenly here was this man who was my real father. So I started to explore my own personal experiences.

4. Studio with gloves (1993)

This seems to be very much about the work of creating art, a reminder to the viewer that what they are seeing is paint; paint in tubes, paint on discarded rags, on the floor, everywhere. Crammed into the top right hand corner is the artist, herself awash in red paint, furtive and skulking, looking as if she’s been caught in a guilty act. Curiously the picture she seems to be working on is black and white and also unusually naturalistic. This picture within a picture shows a female figure with her arms raised and is unlike many of your other representations of the human figure. Do your works have secret meanings or is the sense that they do just part of the intent?

The studio paintings preoccupied me for several years, they were about looking, and discovering the relationship between unfamiliar objects such as squeezed tubes, glass jars covered in paint, plastic containers, tins, all the detritus of a work space. The artist is dwarfed by this space. In this painting the black and white image is portraying a drawing on the wall, the artist is in the throes of painting Studio with Gloves. These studio paintings were a preoccupation with the habitat of the studio, looking at one object against another, the discarded gloves, the rags, the tubes of paint, the tins. Paint covers everything. The symbolism was a mini scaled world of processed industrial materials, often poisonous to the artist. I placed a large poisonous cross on the white tins of lead paint I no longer use. It is almost like a mini industrial city – the gloves are reminders of the need to protect the hands. The viewer has the freedom to interpret these paintings. I just give a somewhat enigmatic image.

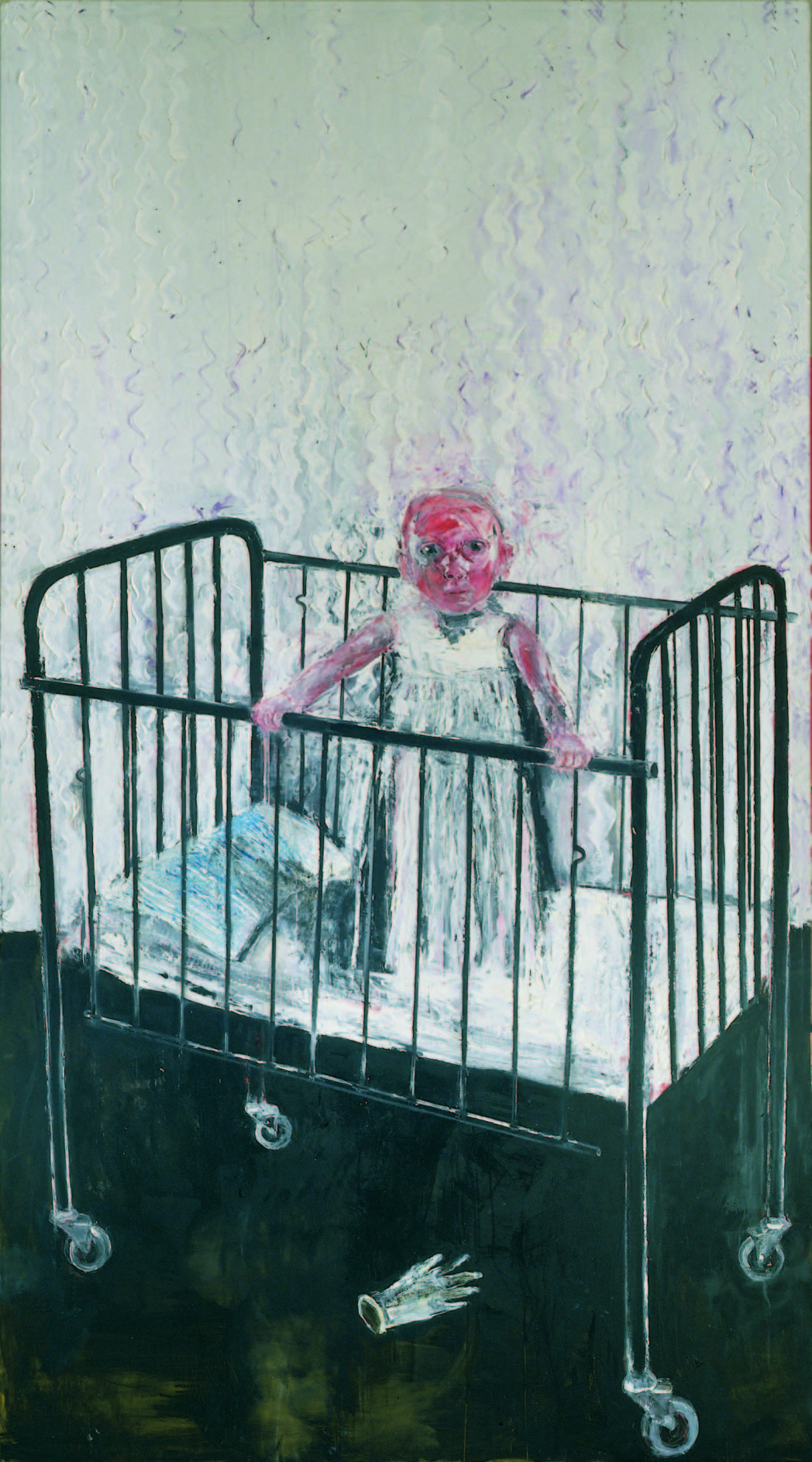

5. Black Cot & Latex Glove (2003)

This seemingly straightforward picture of a toddler standing up in a cot somehow has a nightmarish quality. In part it’s the cot; its cold, black metal bars, its echo of a cage or a prison, but somehow it’s the glove, white like a disembodied hand which gives the viewer a chill; as if it’s the nasty creature that hides under a child’s bed. It makes me think of Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion on the one hand and Mona Hatoum’s Incommunicado which is a sculpture of a similar cot but with a cheese wire base. The child’s expression in your painting is unreadable – she merely looks out at the viewer impassively. Rather like certain doll’s faces they can be read differently according to context. Do you resist an impulse to give much more away by showing a range of expressions?

This is part of the series The Black Cot– a series of paintings with children, adults and cots. The series was started with the Jerwood Painting prize piece, The Black Cot and each painting became simplified until finally it was a giant baby in a giant cot, and yes there is reference to Mona Hatoum.

Whatever way we dress a cot; pad it, hang mobiles, use pretty fabrics, we are in fact putting babies behind bars for their own safety. Just an interesting symbolism. The latex glove refers to birth in a hospital – we want natural childbirth and yet often we end up in hospital under bright lights with doctors in latex gloves. All romance vanishes for safety precautions. Also this refers to my father who was a surgeon and was present at my caesarean birth. The baby simply stares out straight at the viewer open and receptive for what life will throw at it.

6. The Yellow Gloves (1987)

This work, created when painting was having a glorious resurgence, reminds me to some extent to the earlier generation of painters like Carel Weight and John Bratby and Joan Eardley, but also resonates with the work of Paula Rego, Steven Campbell and Kevin Sinnott. I have to confess that when I did a foundation course in the 1970s what I wanted to do more than anything was to paint both figuratively and with elements of narrative. This was strongly discouraged as it seemed to be the age of very formal conceptual art and painting was dead. I know that Mary Griffiths also felt embattled – were you luckier in the colleges you attended or did you also have to fight?

The Yellow Gloves was done in the living room at Dolpebyll when the barn/studio was still a ruin and the house was being restored around us by Stephen. The children were small, we had recently left our house in East London which had been a ruin that Stephen rebuilt while at the Royal College. So it has been a struggle to say the least – so art movements were not on my mind, I was just expressing the intensity of how I felt. It’s more Max Beckman if anyone. The artists you mentioned I admire but I don’t consciously look at, it has to come from one’s own vision, if they have any connection it is by coincidence.

Yes it was a struggle at Saint Martins in the 70’s when abstract expressionism was the order of the day. But I knew that as a figurative artist it would be the case. I went to that art school not naively, I wanted to go to that art school precisely because it was abstract, because I wanted to apply that freedom to my painting, both in the mark making and the colour, in other words not from the perspective of the life room. Even though I love life drawing and actually enjoy teaching life drawing, I found the methods used killed the life out of the model, unlike the French arabesque of Matisse, the wonderful looseness with black ink, the celebration of line was knocked out in the British life class where a model was broken down into lines measured arduously and painstakingly recorded. So going to Saint Martins was approaching figuration from another angle, and the work got looser and looser. I would put the canvas on the floor and move the paint around with turps until I saw forms, figures, faces in the ether of the paint.

7. The Bath (2012)

In your recent work there is a movement away from the colour red and a certain starkness in what I will call your ‘set dressing’ towards gentler colours, now there is blue and gold, there is pink and lilac. There is also some very fancy looking wallpaper and versions of the sort of chandelier seen hanging over the heads of the couple in The Arnolfini Marriage. But in this picture while viewers can recognise certain fashionable trends in home furnishing; the freestanding roll top bath, the over-elaborate and possibly ironic light fitting and most strikingly the ‘accent wall’, all of these elements conspire to create a sort of monstrous room, where the wallpaper is transformed from a pattern of curlicues and other motifs to images of ravens and bats and beetles. The electric chandelier is dangerously low and the bath is reminiscent of a sarcophagus. Indeed looking at the picture I am reminded of David’s The Death of Marat as in that picture the bath dominates and Marat’s head is also shown on the left hand side of the picture. So in some ways there are number of signifiers which point to threat and mortality. Hitchcock’s 1960 film, Psycho also comes to mind not only because the murder famously takes place in a bath with an overhead shower but also for the room filled with stuffed birds and their ominous distorted shadows. Did you mean to reference any of these more negative symbols or is the meaning more straightforward?

All those references you made could be true, the viewer creates their own narrative. The death of Marat is an interesting parallel. A figure is vulnerable in the bath, there is just the head visible, almost a reference to the French Revolution and the consequence of being a person with opulence. It was referencing magazines such as The World of Interiors, luxury seen as a sabot bath with a chandelier suspended, but in this case like the sword of Damocles – an electric light would actually be illegal above a bath. The obsessive interior decoration is perhaps a substitute for something missing in a life- fulfilling a fantasy when once achieved might make the person say, ‘what now?’

You first conceived of the idea of automata in 1994 but didn’t execute any of these until 2006 – it almost seems as if those objects you had been painting had been itching to come alive. It is a curious thing that the very beginnings of art – the Paleolithic cave paintings at Lascaux and the early sculpture The Venus of Willendorf finds the creator fixing the moving world into the stillness of a single moment as if that was the goal – to memorialise for eternity. Movement in art belonged to dance and theatre and later to film – instead of showing these objects in an exhibition space you might have turned to film except of course the audience’s experience would have been far less immersive and real. Do you think it likely you might develop even more automata – or whole haunted houses?

I had placed a mannequin clothed in a Victorian black dress in the painting – The Boards in the 90’s and a hooped skirted mannequin in the painting Stairs I and Stairs II. The presence of these in the paintings had several meanings. The constriction of costume worn by women, mourning for their life after their marriage and the hooped skirt like a cage. I simply wanted the automata to tap her hand, it was like a metronome, time passing. I put a voice inside this mannequin /automata with pertinent passages from Chekov who wrote about educated, privileged Russian women but how frustrated they felt, unable to have any power despite their education. And the complexity of his female characters – sparing with each other, Masha in mourning for her life etc. It was simply something I conceived, it wasn’t meant to be about horror or haunting, it was about pent up feelings of frustration of these women. Masha in Three Sisters says:

Amo, amas, amat, amamus, amtis amant! And I am so bored, bored, bored! (sits up) I can’t get it out of my head it’s simply disgusting. It’s like having a nail driven into my head. When you have to take your happiness in snatches, in little bits as I do, and then lose it, as I have lost it, you gradually get hardened and bad-tempered.

(Pointing at her breast) Something’s boiling over inside of me, here.

Many people find them frightening. They do look best in distressed buildings it is true and they will be shown in Llawn, 20 September for that weekend as part of the Llandudno festival in the old ballroom of a disused hotel They will go to The Millennium Gallery in St Ives from June 5th to July 7th to accompany many of the giant paintings from my studio, some of which I have shown in Distillation.

9. Red Dolls House (2006)

It strikes me that dolls houses have a far greater impact on girls and the women they become than they do on men. Perhaps our generation (raised in the still sharply gender divided world of the 50s and 60s) learned early that the doll’s house was an object of desire. The painter Paula Rego took a set of dolls house furniture with her when she took up a residency in the National Gallery in 1989, I have a miniature wooden cupboard and tiny plastic radio on some shelves within sight as I write this. Actually I seem to remember I decided to buy my first copy of Spare Rib magazine because it had an article in it about women and dolls. Which reminds me that once upon a time the sort of subjects you paint and create – cots, women (with all their clothes on), children, crinolines and other costumes, flowers, china – would have been sneered at and dismissed by the mostly male art establishment. When I was art college in the seventies one of the male lecturers told the entire class that what a slightly quiet young woman student needed ‘was a damn good f**k!’ Have you noticed a great change in attitudes? And has that term ‘a woman artist’ gone for good?

What a monster of a lecturer to say that to a student! He should have been sacked on the spot! That is why I stomped around in boots and a boiler suit and virtually growled if approached by a lecturer in any way like that. Even though I looked quite young and vulnerable in that photo.

You need to see and hear this dolls house. It has been sprayed red. It isn’t about a dolls house as such, it is about the play by Ibsen called A Doll’s house, the first pertinent female tract which was anti the male dominated society of his day, although he saw it more as a humanist play. In this play as you probably know, but I will say all the same, Nora is treated like a doll/child by her husband, but through forging his signature and borrowing money for a much needed holiday to save his life, she is being blackmailed . We find the change in Helmer- her husband’s treatment of Nora in these passages:

Helmer:

‘Is my little skylark twittering out there?….scampering about like a little squirrel? ….has my little featherbrain been out wasting money again?’

And then after the discovery of black mail

Helmer:

‘And now I find you are a liar, a hypocrite-even worse a criminal!’

Helmer then says:

‘We must seem to go on just as before…but only in the eyes of the world of course…but I shall not allow you to bring up the children.’

And Nora says:

‘Our home has been nothing but a playroom. I’ve been your doll wife here, just at home I was Papa’s doll-child.’

The voice within both the Red Dolls House and the Tapping Hand automata was the voice of my mother who had played this part decades before.

This work is not about me confining myself to girly female areas, it is about me exposing the constraints of such objects, the confinement of the garments and the imprisoning of the baby, the wife and the home, all conspiring to keep her spirit, her life under wraps, to intimidate, to undermine and to dominate. Children were treated just as badly. Their spirit broken, seen and not heard, it was a patriarchal society and this has cast a long shadow which is still with us in men’s clubs, secret societies, politics, the places of power where few women enter.

10. Chicken Coop (1996) and Chicken Coop II (1999).

In the first of these pictures three females stand near an orange chicken coop, the landscape behind them looks sparse with dry earth and a burnt-looking tree. One of the women looks older than the other and the third is a child. There is a tin bucket in the background and what might be an old wash tub or bath. In the second version of the picture the child stands alone and the chicken coop is black. Both images seem to represent the Australia of your childhood. Can you talk a little about that?

In the first painting there are three generations of women, my nanna, my mother and me, we lived in a goldminer’s house in a place called Kangaroo Ground, surrounded by 18 acres and there was a creek and broken dams as someone had previously drowned. Nanna panned for gold in the creek and tried to fix the dams with mud. A chicken coop has a mixture of meanings as we moved so often – non specific, a symbol of Oz architecture, temporary, many of our families’ houses burnt down in the Australian bush fires and these houses universally would be left smouldering or replaced by tin roofed dwellings. This chicken coop is symbolic of my nan’s farm in New South Wales, Oz as well. She ran the farm with her two maiden sisters. The original house with cedar stairs and a certain sense of permanence burnt down. If you have read Patrick White’s Tree of Man you can get the flavour of the place, the bush, the birds, the sky, the colour and the determined dogged people overcoming adversity. My nanna could plant 60 trees in a day, digging by hand although she had pernicious anaemia and was the gentlest soul. I never saw her after the age of nine; she died when I was 17. The tin bucket is just the debris on a farmstead and there is also a roll of barbed wire. The child standing alone is the realisation I had at eight that I was alone and not actually attached to anything, the chicken coop in this painting was my doll’s house. I waited ages for my step-dad to make me one, he promised but it never happened so I took over an old chicken coop at the end of our garden after we moved from Kangaroo Ground to Eltham (a suburb of Melbourne). When we left it burnt down too. It sounds hillbilly, but we had paintings on the wall, and handmade pottery and antique/old furniture although we were lit by kerosene lamps and had a dunny and a tin bath in Kangaroo Ground. In Eltham we had electricity; it was a miracle to turn on a light.

Shani Rhys James © Copyright

Distillation is on until 31 May Gregynog Gallery National Library of Wales , Aberystwyth 2015

Antigone Automated June 5—July 7th Millennium Gallery St Ives 2015

W.A.S II— Women’s Art Society II mixed show 17 July-1 November Oriel Mostyn Llandudno 2015

16 September- for a month Connaught Brown Mayfair London 2015

16 October-29th October Macy Gallery Columbia University New York 2015