In the week of Stan Lee’s death, Craig Austin reflects upon the artistic and cultural impact of the legendary writer, editor and publisher of Marvel Comics.

Every second Thursday I enter into a physical tussle with my 10-year-old son almost as soon as my key is in the door. The latest issue of The Astonishing Spiderman is swiftly wrestled from my bag and I am presented with a perfunctory hug before he spirits himself away upstairs. His total immersion in the latest instalment of the multi-layered Spidey saga is not an experience to be shared, it is personal and private, one to be enjoyed behind closed doors; a joyous exercise in the escapism that has traversed both generations and languages.

To this, he owes a wealth of gratitude to the pioneering Marvel triumvirate of Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby, and Stan Lee. The former – a psychedelic artistic visionary, lost to us only a matter of months ago – the latter, the towering creative director of a global fantasy franchise whose primary characters were forged in the flames of humanity’s seemingly endless imperfections and flaws. A man whose death has evoked a surfeit of raw personal tributes that draw parallels with those that accompanied David Bowie’s untimely death. When Seth Rogen publicly thanked Lee ‘for making people who feel different realise they are special’ a clear line was being drawn between Bromley and the Hollywood Hills.

As a child, Marvel comic books, along with Bazooka Joe bubble gum, were my first exposure to undiluted Americana. The language of its characters, the intricacy of its stories, even the smell of its pages; all of these things were different, exotic and exciting to me. Inevitably, I chose Marvel over D.C. in the same way that I would later choose Glasgow over Edinburgh, and Macca over Lennon. Life is too short, and you need to pick aside. Stan Lee knew this too, though he was a world in which good versus evil was often tinged with the often stark acknowledgement that life is rarely that straightforward.

For me, the choice was an easy one. Marvel’s characters were irreverent and perhaps most importantly, young. I could empathise far more easily with a skinny permanently perplexed Peter Parker than I could the lumpen, square-jawed, and now decidedly middle-aged Batman. This was after all a pre-Killing Joke caped crusader, one yet to be touched by Alan Moore’s dark complexity, who had seemingly hit the wall of a midlife crisis and was now nagging me at school about not falling into the filter-tipped clutches of the wheezing yellow-fingered, fag-crazed ‘Nick O’Teen’.

These comic books were a world away from the flimsy British comics I had been used to up to that point; a fading genre still seemingly rooted in the 1950s and its long-redundant language of ‘tee-hee’ and ‘chortle’. Perhaps most importantly, they also gave me my first insight into an adult world and its attendant imperfections. Stan Lee was in the process of handing over creative writing duties to a new generation of visionaries at the time, but it was his vision that gave me an early awareness of the existence of adult frailty and an acknowledgement that the narrow and safe world that I inhabited would one day be invaded by a maelstrom of thrills, danger and insecurity.

Lee’s characters, for all of their physical and scientific genius, were often damaged and compromised. They were not necessarily muscle-bound or all-conquering; they suffered from self-doubt and questioned the world and the universe around them; they were not necessarily successful with girls and, in a particularly brave and groundbreaking move, they were not always white. ‘I have always included minority characters in my stories, often as heroes’, Stan Lee once reflected. ‘We live in a diverse society – in fact, a diverse world, and we must learn to live in peace and with respect for each other’. In 2016, Lee created the RESPECT Initiative to, in his words, ‘encourage people to be more accepting and inclusive of others’.

With this in mind, Lee must have taken a huge degree of personal satisfaction at the global critical and box-office success of 2018’s Black Panther, a pivotal character borne out of the civil rights movement and the first superhero of African descent to appear in a mainstream American comic (only a matter of months before the formation of the infamous Black Panther Party itself). In a 1968 Marvel column entitled ‘Stan’s Soapbox’ the writer notably describes racism and bigotry as ‘among the deadliest social ills plaguing the world today’.

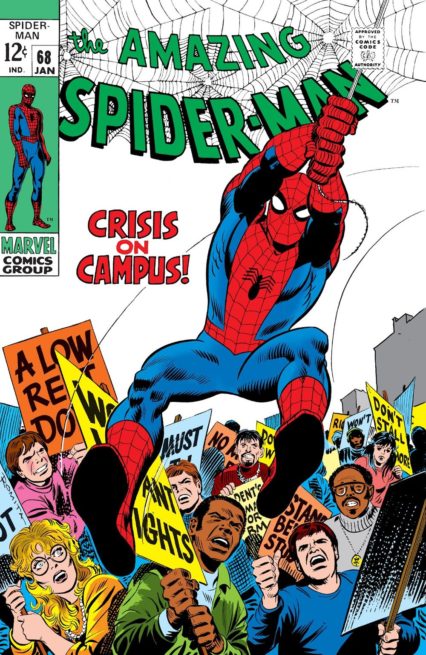

It’s important to remember after all that Lee’s Marvel was never an apolitical beast. In January 1969, Spiderman appears in a pre-Kent State cover story titled ‘Crisis on Campus!’ in which he makes it his web-slinging business to clear the names of a collection of radical student protestors; a story within which the Kingpin notably plays the boo-hiss 60s embodiment of ‘The Man’.

Lee created a fantasy in the minds of kids whose waking hours were often steeped in mediocrity. He was no saint, as the long-running legal disputes about the contribution (and resultant paycheques) of his co-creators attest. Yet his work inspired great thoughts, the pursuit of great deeds, and a sense that the possibility of human achievement was not always constrained by the hand that you were dealt at birth, at school, or at work. Most importantly, Stan Lee should be remembered as a great artist, and yes, a literary luminary.

‘I used to be embarrassed because I was just a comic book writer’, Lee revealed during an interview at the 2010 Comic-Con in San Diageo. ‘…while other people were building bridges or going on to medical careers. And then I began to realise: entertainment is one of the most important things in people’s lives. Without it, they might go off the deep end’

Amen, and ‘Excelsior!’ to that.

The website for Stan Lee‘s Marvel Comics has thorough information on Marvel’s current and past projects.

Craig Austin is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.