Born in South Devon, John Hardy is a significant composer more usually regarded as Welsh, having been involved with Cardiff’s cultural life since his mid-teens. In stark contrast to Herefordshire, where his family then lived, the Welsh capital offered exciting stimuli for the developing musician and composer. Welsh National Opera was enjoyed, as well as radical, experimental theatre; both just a short train journey or a hitch-hike away.

“Seeing Mike Pearson performing mostly naked, wordless theatre was unforgettable when I was 15, 16, 17 and I’m proud to say that I still work with Mike Pearson today. Some of those character that were doing things for the first time ever are still pushing the envelope and finding new ways to say things even to this day.”

With the third season of noir-drama Hinterland currently on our screens, much credit for the show’s lingering mood and atmosphere must go Hardy and his production company, John Hardy Music, for their darkly evocative theme and incidental music. Hinterland is just one of more than 350 pieces of original music composed for productions since JHM was founded in 1980. Working either alone or more commonly within his composer collective, a diverse range of commissions has seen Hardy work in fruitful collaboration with theatre, film, radio and brands including last year’s gracefully inspiring ‘Visit Wales “Find Your Epic” campaign’.

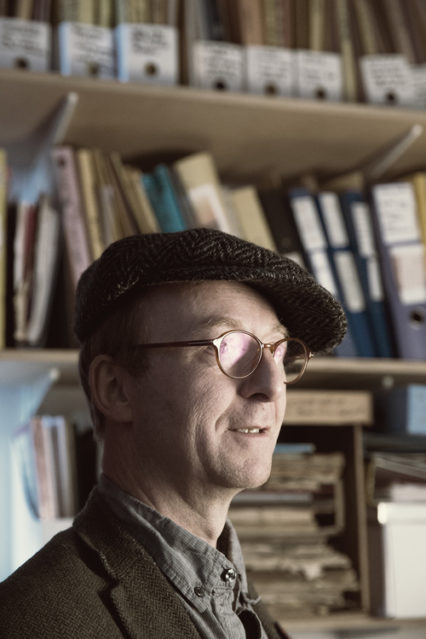

As Head of Contemporary Music, Composition and Creative Music Technology at the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama in Cardiff, Hardy’s work life is a tightrope of creative deadlines and guiding the development of the next generation of music creatives. Speaking with John Hardy one afternoon at the college, we enjoyed a far-ranging conversation. Topics including the politics and joys of commissions, the corrosive nature of arts awards and the undeniable responsibility towards one’s creativity, revealed a number of touchingly open insights from the critically acclaimed composer.

Jane Oriel: Although your collective goes under the name ‘John Hardy Music’, are you always the instigator of an idea or direction when a commission comes in?

John Hardy: Well no, absolutely not. We work very collaboratively and depending on the circumstances, one of the collective will either undertake to come up with a particular ingredient or develop something further once something has been started by themselves or someone else.

Is it common for commissioning clients to try to guide where you go, or do they leave you and your processes completely alone?

They do, they very much do, and it can be frustrating sometimes because although one is often grateful for a brief to react to, there’s often the idea that the person you’re talking to thinks they know how it’s going to be, but they don’t really know yet.

At its best, it’s not interfering; it’s beneficially giving support and suggestions, acting and responding positively and asking for more. It can be very exciting and lovely when that happens. At its worst, either because you’re up against it and there isn’t time, or sometimes because you just disagree with the person who’s hearing what you’ve done and you think it’s great but they want it changed (especially if they want it to be something less and more formulaic or cliched), that can be very disappointing and one sometimes feels like you’re murdering one’s own children at someone else’s request.

Have any briefs been too complicated or unfathomable that have resulted in both parties walking away?

Yes, probably but not very often in my case. I think when I was younger I used to become involved in projects that were against what I was comfortable with. As I’ve got older, people automatically select or deselect themselves according to the energy they give off. Generally speaking, I’ve used up huge amounts of my creative life energy in doing my best to interpret, be empathetic towards and to match the thing I thought I was being given to react to, and that’s true of films, television drama, song writing or ballet, plays, online projects; all sorts, really and I’ve enjoyed the challenge. It’s been a sort of mental puzzle that most of the time is fun to engage with.

How often do you get the opportunity to write something for yourself purely to satisfy your own emotional needs?

Reflecting just recently, I think it’s now time for me to perhaps take a bit more ownership of the initiation of the idea, maybe just once in a while, and to explore things and to make more decisions and not expect someone else to dictate the starting points. I’ve written operas and orchestra pieces and the like when you have some kind of starting point such as an orchestra or you’ve got and opera subject or you’ve got whatever it is that’s outside of the music itself that helps the composer to make a start. It’s a different type of discipline to make a decision or to make an abstract decision and then later worry about how I’m going to get it out to my people.

I suppose really, we all choose our arts because of how they feed us, and it’s not really about assembly lines. It’s about feeding yourself really, isn’t it?

Yes absolutely. And I think that’s where, for a lot of musical people, that’s where the initial impetus and drive comes from; to be a professional musician. In my case, I think it was a therapy. I think as a child… Maybe that’s over-interpretation. Maybe it was just a natural response from a very, very young age to sound and sonic possibilities, and musical shapes and patterns and emotions that seemed to grab me. But certainly, as I grew older, music was my safe place that I could go where nothing could touch me. Where I could dream, where I could be separate from people and situations that maybe I wasn’t comfortable with and, um, what’s strange in a way, is that it’s always been a way for me to make a living throughout my life.

In one way that’s great, but it also puts a pressure onto it. For many, many years I was entirely making a living from being a freelance composer before I took on the role at the college, and I’m sure for at least two-thirds of that time there may have been great enjoyment and there was (I had such fun). But at the same time, there was always a pressure – will I get the gig? Will I get the commission? Will I get paid? What’s the budget? Can I keep this money going until the next thing in 6 weeks’ time? But if I can’t, will I have to sell my instruments?

There have always been those kinds of pressures, and negotiating those feelings and fears has always been mixed up with the joyful processes of making art, as you might call it. So, really the question is: is that good? Does the one need feed the other? (As they say, necessity is the mother of invention.) Or is it actually a happier person who’s doing it as a hobby, as an amateur composer or music maker? Maybe there isn’t the impetus as an amateur musician, that while there might be a lack of worry, the lack is unlikely to push you to reach the heights in the same way?

But I don’t think everybody has to reach a universal idea of whatever those heights are. I think the heights can be different for different people at different times of their lives. It’s OK to reach for the heights where nobody gets paid and everyone does it just for the fun of it, just as it’s OK to reach for the heights that have taken three years of painstaking work and only gets one performance.

Perhaps a more important question to ask would be – is the communication authentic? But what kind of criteria do you use to find out if something is authentic or convincing? I do think that’s a good question for a person who’s taking their artistic creativity seriously to constantly ask themselves.

That’s quite something to process and reconcile for a creative. But on the other hand, JHM have been awarded 5 BAFTAs for Best Original Soundtrack Music, and so how people choose winners in arts is such a complicated thing. How can people choose which art is worthy of an award?

I’ve been on BAFTA committees so I know too well how haphazard and random sometimes the decisions are, and I’ve been on those panels where I’ve completely disagreed with the end result. It’s very hard to be genuinely fair or genuinely reflective in those situations, as quite often, compromises are made.

It’s fraught with difficulties because what are the credentials? You can’t help wondering why there are awards in the art world because by their very nature, these things can’t be measured.

Yes indeed, well why are there? I suppose it’s to reward the efforts but with the idea that there’s a winner that takes all and that everyone else is a loser, I disagree. I think it’s insidious and corrosive.

Also, with Hinterland we’ve been unable to enter certain awards (I won’t name them) several times because, one time, there weren’t enough other entries, another time it hadn’t been broadcast in precisely the right time window and other reasons. There are always reasons why you can’t actually get your one chance to get the recognition that you partly crave, and you just have to develop a thick skin and tell yourself that you don’t care.

Could you tell me something about your working processes? What’s the starting point apart from a brief?

Well, I suppose, our own interests for a start. To take Hinterland as an example, we had abilities and interests and obsessions and the series seemed to be giving permission to delve into some of those and when we first started working on Hinterland, it was Benjie (Benjamin Talbott), Tic (Ashfield) and myself who we allocated to work on it. I was approached first with a very enlightened invitation to include students or recent graduates if I wanted to. And I did want to; I knew that it would be huge in scale and I would need some help – and not just in terms of compositional ideas but for the sheer mechanical processes that have to be accomplished within the time frames that are available. So we divided up some of the labour, and in the very first episode some of the main sketches of melodies and themes I did, because I was just used to doing that. So I jotted things down on paper and the others put in their ideas as well. Benjie did the stuff that needed fast, driving, mechanical, techno-type rhythms for chase sequences and that kind of thing, and Tic was allocated the role that suited her way of exploring pure sonics, abstract sound worlds that weren’t so much about harmony and ‘musicality’ but suggestive of other sound worlds made from distressing pieces of metal or bending things or scraping.

We all worked on those things together, but in terms of initially taking responsibility for areas, we made sure that each developed in confident parallel with the others. Those were the initial delegations and over the course of all three series, they have been moved around and shared with each other. And we have Sam Barnes working with us now. He worked on Series 3 in its entirety.

You’ve mentioned the different sounds and textures that Benjie, Tic and latterly Sam all bring to the project. Do you choose your team because of the distinct elements they can bring?

Partly, but also their personality, their ability to be completely professional and the quality of their ears and listening, and their track record in each case of behaving in a professional way as both composers and sound engineers. Sound engineering is something I’m not good at. In fact, I’m scarcely trained at all so I know that I will always need people who are much more highly trained than I am to function in that world where everything has to work to a very high standard within a set time range.

I’m quite happy working with an orchestral palate for live orchestra. But if it’s something that involves getting your specialist microphones out and your microphone positions or recording the inside of the piano or creating pure sound from analogue or digital synthesis from scratch or any further sourcing that requires a high degree of technical mastery and training, then I would not be the person to take that through the process. I’m very proud of these former students of the RWCMD who have been endlessly skilled and endlessly questioning.

Your website is full of your previous work as well as a great number of recent soundtrack commissions, many of them for TV documentaries outside of Wales such as the TV series, Andrew Marr’s Great Scots: The Writers Who Shaped a Nation. What is the next piece of work that the public will be able to hear?

We’ve just been working on a movie called Steel Country but don’t know when it will be released as these things can take a very long time. It probably won’t enter into the big festivals until the autumn. I can tell you that it stars Andrew Scott who’s the Irish Moriarty in Sherlock but it’s set in the United States and they are American characters. It’s set in Pennsylvania, the sort of rust belt country, although it was actually filmed in Atlanta, Georgia last September. It’s very characterful and not a high budget. We obviously hope that it will be shown in cinemas and distributed widely and that people will like it, as it will help to open doors for us for future film work.

We also have an interesting dramatised documentary about the 1917 October Revolution in St Petersburg and then Moscow, and there’s a drama series in the second half of this year that we hope will come to fruition (it’s looking very promising). We also have plans to release more material of our own as album projects. We want to release probably 3 or 4 different things in the next 4 months to build up our shop window of recordings that we are very proud of and want to share with people.

In terms of my personal work, I am only now starting to connect with an element of my personal creativity that I had rather put to one side. I’ve obviously spent a lot of my creative energy trying to help and encourage young composers (and sometimes older composers too) and other creative people and that, well, you know… I often think to myself that I could try to promote a work of mine that I would like to have re-performed or that I would like to have the opportunity to write something. It’s not just the students, it’s the members of staff here that are so talented that when it comes down to it the question is – do I give energy to supporting them and their work to try to give them opportunities, or do I put that to one side and try to push my own personal work and try to get opportunities for myself? This feels as if that can only be done at the expense of other people. It’s a very difficult one, that. And I think that since I started working at the college in 2010, it’s been difficult.

My natural solution to that dilemma has been to try to work collaboratively and in media where collaborative working is natural and already established, and not to push for things that require a more selfish, individual approach. But gradually, I’m arriving at a place where I am remembering how to be more confident about my own personal voice, just as I try to encourage the students and the tutors at the college here to be. I don’t even know if it’s going to come to fruition but some time over the next year, I’m hoping to be a bit clearer about all that and to be able to talk about it a bit more and to devote a little bit of time to developing things that are perhaps more private to myself as well.

I have to say that’s a rather important step you’re taking.

Thank you.

I think you are the main issue here. You’re very good to them but you are not responsible for their successful lives or otherwise.

Well I do feel responsible, I really do. You know, my job? I am responsible. And for the colleagues who have left the college and continue to make wonderful contributions both to their own work and to their group’s work and to my possibilities. You know, I am responsible. Without me taking responsibility for them and making sure there’s some money to pay for their time, so they can continue to live and function as human beings, I feel that I am responsible, I really do. I just feel that I’ve not taken responsibility for my own private creativity because I’ve felt that it was enough, or that it was all that I could manage, to take responsibility for my shared creativity in recent years.

John, you need a mentor!

Yes, maybe I do. I can be young again, haha. And maybe my best mentors are the very younger people who I’ve, in the past, been a mentor to. I can learn a lot from them. Well I do. I do learn from them constantly actually but perhaps in a little more of a formal way. Perhaps I could turn the tables and let myself be overtly taught by people who are younger, and not just people who are older. But it’s also a question of time and choosing the right medium to do this exploration of personal creativity.

There are so many possibilities and I can’t do them all, so I will have to choose whether it will be something long and big and takes a long time and either does or doesn’t reach an audience (something like an opera or a big symphonic work because the labour involved in something like that is staggering). Or whether it’s something more personal, for example me performing: myself in a space with or without help from others. And in a way, that could potentially be very, very small. It could also be quite immediate and honest. If I can find a way to be truly authentic and honest with that work, then maybe that would be a place to start from, but I’m not quite sure yet. I’m still thinking about it.

John Hardy’s website: http://www.johnhardymusic.com