An acclaimed portrait artist with a traditional training at the internationally renowned Charles H. Cecil studios in Florence, Daniel James Yeomans paints from life under natural light at his purpose built studio in Montgomeryshire, Wales, where his sitters are immersed into the world of classical portraiture – an enchanting form of painting which remains unchanged since the Renaissance. As well as specialising in portrait commissions, Daniel also spends much of his time travelling and painting landscapes, some of which hang in collections throughout Europe and Asia. Daniel’s solo exhibition is currently on at the Willow Gallery in Oswestry (until 4th November 2017). Writer Julia Forster interviewed Daniel soon after the exhibition opened; she’d recently sat for a charcoal portrait, and has also been bringing her energetic ten-year-old daughter Matilda in to the studio to sit for a portrait in oil paints.

You trained in the sight-size method at the Charles H. Cecil studios in Florence. Can you tell us a bit about what this method involves and why you think it’s important in contemporary portraiture?

The term ‘sight-size’ describes a technique of painting from life whereby the painter stands back from the canvas to see both the work and the subject in one glance. This makes it easier to flick your eyes between the subject and your painting and to judge shape, proportions and colours.

In itself, the sight-size method is ever so simple. It’s a tool, and like many practical skills, plenty of good practice under a watchful eye is the best ingredient for success. A good maestro will focus on the method becoming second nature over time, meanwhile teaching students how to look, and what to think about while you are painting. (Which, in my experience, is the part most overlooked).

Sight-size doesn’t claim to be more important than any other method –

there are many roads to Rome – but the main lessons I have learnt come from painting from life. Learning the sight-size method taught me to take my time. That ‘higher beauty’ so often spoken of existing in great works of art takes time to realise; it doesn’t appearing accidentally. With portraiture, you need no less than the first-hand reference of a real model which in turn provides endless variety and brings malleability to the canvas enabling you to improve your work as you go along.

Whether you’re an abstract artist, sculpturer or hyper-realist, there is more to gain in so many ways from the complexities of changing landscapes and conversing, moving people. You don’t get these aspects with a second-hand reference such as when painting from a photo. Like any shortcut taken, maybe you arrive at the destination sooner, but you can only take in half the view along the way, and that viewing time can vastly improve your ideas or change your perspective along the way.

The quality of light in the studio is crucial to your work as a portrait artist. As a sitter, I noticed that even the slightest tilt could affect how you worked because of the resulting shadows and tones that were changed. You also often hold up a mirror to trick your brain and cause the sitter’s face to become an amalgam of abstract shapes. Can you say something about how your training has changed the way you look at faces as you paint them?

Quality of light is paramount. The inherent drama in the light is that extra something every artist, every photographer, every stage director searches for. If you’re seeking to create space with atmosphere and transfer that to your 2D canvas in a naturalistic manner, really careful attention should be given to the chiaroscuro in painting. For myself, that means using natural north light, and a large studio space which affords options of light direction.

One thing I began to realise during my studies is that we are so often self-approving of what we are painting; quite often, after a long stint, I would take a break and come back to what I thought was going well, only to see so much room for improvement. So the mirror is my ‘proof-read’, it jolts my eye and helps me see mistakes by turning all the features of a face into the abstract, helping me to avoid painting any automatic shapes I might draw as a result of pre-conceptions.

Which portrait artist influences you the most? Do you see your work as being in a dialogue with the old masters of portrait artistry, and if so, how?

I’m inspired by so many artists, right through from old masters like Rembrandt and Velasquez to more modern artist like Klimt. Some for brush work, some for composition, others for colour. I’m a great believer that you can always improve, and if you study different styles of work you begin to understand what different qualities you can bring to your own art. What I am aware of when looking at the old masters’ paintings is the presence of the sitter and the presence of the painter: you can see the brush marks, the mistakes being painted over, composition being changed. For me this is the real dialogue I feel between the masters and me. It is purely the fact that I am overcoming the same difficulties that they also faced daily. It is humbling as a painter to see this; you begin to realise that with much endeavour great painting is quite attainable.

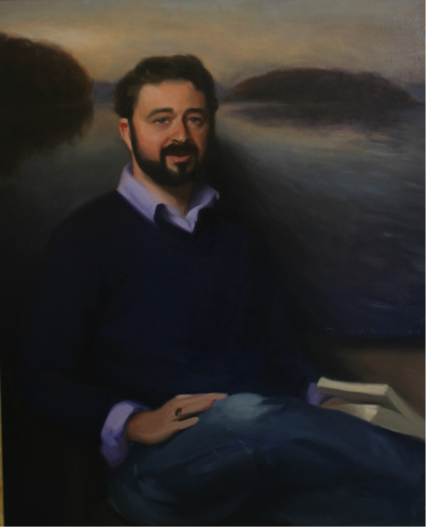

One of the things I observed while watching you paint Tim’s portrait, which is now on exhibition at the Willow Gallery in Oswestry was how the composition of the portrait is fluid. In the process of painting it, you changed the objects on the table and also in the background. Can you say something about how you choose the setting for each portrait, and how this evolves?

Ha ha! Yes: fluid, although it is not without struggle and a lot of head scratching. The thing with painting is, what you see in a 3D space (the world around you) or the room in front of you, does not always translate well on to a 2D canvas. It takes time to learn what works and what doesn’t. Each painting comes with a new problem to solve and there are definitely some unwritten rules when it comes to harmonising a composition. When I have created the idea on the canvas I then start to aim for that ‘higher sense of beauty’ or the ‘cherry on the top’ and arrange the background or sitter in a way which seems accidental but also provides balance in colour, tone and shape within the painting as a whole. There are no accidents in painting, everything is carefully thought out. You’ll know a clever painter when the whole image sits well, but all the components seems so effortlessly painted.

With your portrait of Jonathan Herbert, Viscount Clive, also on display at the Willow Gallery, I noticed that you also changed his seated position mid-composition. How much does the sitter influence the portrait, and how do you find ways to communicate each individual’s spirit and personality in the painting?

Paint from life, talk to your models, don’t tire them too much, keep your brush work accurate but confident. A fleeting moment can change a sitter’s expression and when you see the one you want, put it down without hesitation or fiddle. I try to keep my sitters at ease, whether it’s with coffee, music, podcasts, or just talking life. Some people are also quiet. The key is to let people be themselves, make them comfortable. I love my profession and I think that helps people to enjoy their experience in the studio.

If I’m painting a character or commission (as apposed to a themed figurative painting) the aim is that the sitter influences my painting in as many ways possible without them realising. I am in control, but sometimes that control is actually just letting the model sit down naturally without my saying too much. I can stand and view their posture from any angle, take advantage of their character, expression, and use that in my work to help communicate with the viewer.

In your landscape work, you paint in plein air. What kind of logistical challenges does this bring to the work (perhaps especially bearing in mind that you are working in the Welsh climate)?

Commitment and patience are key and I suppose you need to be quite adventurous. I’ve always loved being outdoors. I’m a keen skier, mountaineer and cyclist and I revel at the idea of a good challenge, so that part I actually quite enjoy. I like the idea of paintings being autobiographical: a scene which brings intrigue or joy is also a story of the artist as well as the moment. Logistically, my set up is quite efficient. I can get everything in a backpack, with a canvas attached to my bag and trundle off to wherever I like. I’ll often do plein air painting ‘trips’, rather than day trips, whereby I will select an area to work for that week. I take a separate canvas for each time of day and place, repeating the same schedule each day until the painting is finished. If the weather changes I can choose not to paint or to start another study.

More often than not, landscape studies get better over time; you can take the best part of each visit, going back to the fact that nature gives you endless variety to work with. Clouds are a good example: one day you might paint them in and the composition doesn’t balance, but the clouds the next day give perfect harmony. Quite often, it’s a stake out: it’s just about waiting for those moments.

With your self portrait you painted yourself in the process of painting yourself, perhaps coining the hashtag #SlowSelfie. What did you discover in the process of being both model and artist?

Surprisingly they are very similar to any other portrait. It becomes difficult when you start to draw your own hands, due to the fact that you need to move them each time to paint! However, you can be really experimental, create any composition, always throw it out when it’s going bad so it’s free testing time at nobody else’s expense. From a painter’s point of view they are great practice if nothing else.

What have been the main challenges of painting a wriggly ten year old?

I’m often surprised how often children take to the experience and begin to really look forward to sittings. Up to a certain point it becomes quite a novelty for them and boredom is seldom one of the problems. Plus, I quite enjoy baking, so if there is ever a need for it bribery is always an option.

I suppose the main hurdles to overcome are similar to those of painting an adult sitter, but they’re perhaps exaggerated. Children are slightly less predictable, they need a little more entertaining and patience on my part. The greater the challenge, the bigger the reward though, right? It’s especially enjoyable to paint a child as an artist. You’re painting someone who has no pre-conceived ideas of a portrait painting and the child sitter is not worried about how they might appear on canvas; that innocence in itself makes it quite relaxing to paint.

Your collaboration with the Newtown-based filmmaker Gwyn Cole resulted in this film. How important is inter-disciplinary collaboration with other artists in your practice, and who would be your dream collaborator(s)?

Being independent, it does help if you can be resourceful and dynamic. I find working with like-minded people, in different fields, not only very enjoyable but a great way to widen your creative visions and skills in other areas. I’ve been mulling over a few collaborations with other artists and various ideas for a while now, and not long back had a chance meeting with one of my all time favourite comedians, Noel Fielding. With that in mind, I’d have to say he’d be at the top of my list of collaborators. I have quite a classical method so it would be fun to create something which brings together classical painting, with his modern art and edgy comedy. We will see what the future brings!

What new projects are on the horizon?

Well, without revealing too much, I have some ideas for another charitable project regarding natural disaster zones so you will need to watch this space for more info there. Until then, I am off to the Swiss Mountains to paint a collection for my next solo exhibition, which will be by Lake Geneva in early springtime 2018. I’ll be out and about with my ski touring/painting set up, exploring some ‘hard to get to places’, making a vlog in the run up to the exhibition following my progress – showing people behind the scenes of some of my most exciting painting trips and most importantly what keeps my inspiration ticking.

Daniel’s exhibition is at the Willow Gallery in Oswestry until 4th November 2017.

You can follow Daniel on Instagram, Twitter, his website is here.