Penny Thomas talks with Julia Griffiths Jones, winner of the Eisteddfod 2017 Gold Medal for Craft and Design.

When Julia Griffiths Jones opened a magazine at a feature about folk art in the former Czechoslovakia she knew she had found something special, but couldn’t have imagined how it would shape her work and life.

Years later, winning the Gold Medal for Craft and Design at the National Eistedfodd with her wonderful ‘Room within a Room’ recreation of the inside of a Welsh cottage, made entirely from wire, she looks back to this moment as the start of an amazing journey.

As a young textiles student from West Wales in the rarified atmosphere of the Royal College of Art in the Seventies, Julia had won a travel bursary to go abroad and study, the only catch being that she had no idea where she wanted to go.

As a young textiles student from West Wales in the rarified atmosphere of the Royal College of Art in the Seventies, Julia had won a travel bursary to go abroad and study, the only catch being that she had no idea where she wanted to go.

‘I can see myself standing in the library looking through the magazines for ideas and finding an article about folk art, and it featured a village, Strasnice, in Czechoslovakia. This village had decoratively painted exterior patterns on the buildings that I fell in love with. The aim of my journey would be to find that village.’

‘It was quite random. Before that I had never thought of folk art at all. I used to draw my environment, and wrought-iron work, I was studying textiles but when I saw this folk art it looked amazing.’

Julia travelled by train from London to Warsaw and then down through Poland to Krakow, Zakopane in the Tatra Mountains and then across to Strasnice. And all this before the fall of the Berlin Wall, so at a time when people behind the Iron Curtain saw very few westerners.

‘They thought I was barmy,’ said Julia. ‘I was wearing legwarmers for a start and people didn’t do that there.’ Julia sketched as she travelled and recorded what she saw on rolls of till receipts, another oddity for the locals to get to grips with. But the terms of her scholarship also gave her an interpreter who was an ethnographer and who helped her to find the people and places she needed.

She remembers: ‘My heart was beating very fast when I arrived in Strasnice as the station building was covered with painting, around all the windows and doors and along the eaves. It was a white building with flecks of blue, orange and red. As I walked through the extremely quite village it was lovely to see virtually all of the buildings painted with patterns, modern bungalows as well as roadside shrines.

‘In the UK there was very little folk art around back then. Now we see it every day, blouses in Monsoon etc, but it wasn’t fashionable at the time. I remember it wasn’t thought very commercial for textiles. My tutor advised me to study flower designs instead as he thought they would sell better. Usually I listened to everything I was told but I made a decision that I wasn’t going to listen to that advice even if there was no one else was doing this at the time.

‘What I loved was the formation of the forms – you can see a pomegranate embroidered onto blouses, then painted somewhere else. They have made natural forms into symbolic forms into really fascinating patterns, plus red embroidery on white linen is so beautiful. I loved the simplicity of the lifestyle, that everything they made and wore was necessary, so if you had a chest to put your blankets in, the chest would be carved and painted so it was utilitarian and beautiful, and you had to have these things, you had to have clothing. Then I found out that all embroidery was seen as really significant in that it protected you from evil spirits or helped you to have children – fertility. It’s a very ancient skill in Slovakia and if you wore your embroidery when you went out of the home, when you were out on the road they believed it would still protect you. So it’s decorative and also symbolic, a very old connection with belief. The different patterns were passed down the generations.’

‘What I loved was the formation of the forms – you can see a pomegranate embroidered onto blouses, then painted somewhere else. They have made natural forms into symbolic forms into really fascinating patterns, plus red embroidery on white linen is so beautiful. I loved the simplicity of the lifestyle, that everything they made and wore was necessary, so if you had a chest to put your blankets in, the chest would be carved and painted so it was utilitarian and beautiful, and you had to have these things, you had to have clothing. Then I found out that all embroidery was seen as really significant in that it protected you from evil spirits or helped you to have children – fertility. It’s a very ancient skill in Slovakia and if you wore your embroidery when you went out of the home, when you were out on the road they believed it would still protect you. So it’s decorative and also symbolic, a very old connection with belief. The different patterns were passed down the generations.’

Julia made many visits to Eastern Europe, living in Bratislava for six months and in Poland, and began to develop her own distinctive style of drawing.

Growing up in Aberaeron from an artistic background she had always been drawn towards art as ‘it was the one thing I could do better than any other’. She had an art teacher at the grammar school who encouraged her to look beyond Wales and she studied in London and Winchester before heading for Eastern Europe for her inspiration. But it took another teacher to direct her back to her roots and advise her to study her own folk culture too.

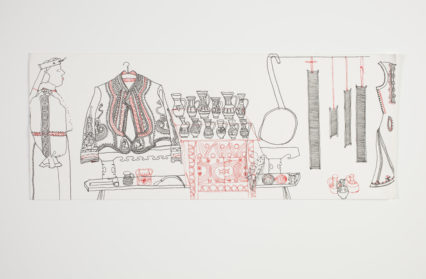

Julia who now lives in Llanybri, said: ‘I never thought of relating what I did to Wales, but when I did start looking I found so much. But it was very grid-like and no embroidery so I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to do anything with it. Then I started drawing Welsh costume and had the idea for merging the two together. There was a strong similarity in that life was lived in small spaces in both Wales and Eastern Europe, everything going on in these tiny spaces; a weaver for example would weave upstairs and live downstairs.’

Julia who now lives in Llanybri, said: ‘I never thought of relating what I did to Wales, but when I did start looking I found so much. But it was very grid-like and no embroidery so I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to do anything with it. Then I started drawing Welsh costume and had the idea for merging the two together. There was a strong similarity in that life was lived in small spaces in both Wales and Eastern Europe, everything going on in these tiny spaces; a weaver for example would weave upstairs and live downstairs.’

Julia has always also taught art. She is currently a senior lecturer at UWTSD/Swansea College of Art, and has been awarded several Creative Wales and British Council awards. But her own work took a new twist when she started to use wire and make metalwork rather than drawings.

‘I wanted to make my drawings come off the paper,’ she explained. ‘I wanted to make them and feel them and hold them and look around them. It was very difficult and I was sort of making it up as I went along. I realised quite quickly that I would have to learn how to weld, I couldn’t just wrap it together, but I couldn’t even turn the flame on. I took welding courses, the kind of thing you might have done in metalwork or as a blacksmith, and in the end a very patient man, Elgan Evans in Llansteffan, who is a welder taught me. I realised it was working when I made work that didn’t fall apart. It became more stable and professionally finished. It’s not enough just to have a great idea, you have to have a good finish too.’

‘Not many people in this country work with wire, that I’m aware of. I was inspired by the work of American sculptor Alexander Calder. I’d been to America years before and seen his amazing exhibition. But I wouldn’t call my work sculpture, it tends to be two dimensional, very flat, I think because I trained as a designer. I’m inspired by the work of embroiderer Alice Kettle and artists such as Matisse, or Paul Klee’s wiry line drawings. I look a lot at work by people who draw and I’m also inspired by the work of people who make textiles, in particular a Dutch embroiderer called Tilleke Schwarz.’

At this point around 2004, Julia had an exhibition of wire work called ‘Stories in the Making’ with many of the beautiful wire dresses she makes coming from that period. But the idea for the wire room arrived when she visited the local museum at Abergwili and saw a recreated traditional Welsh kitchen encapsulated in another room.

‘You couldn’t go in, just look from the threshold which was irritating but also magical; you could think about all the things that might have happened there.’

‘The room is full of domestic objects though not food or people. ‘That’s not what I do,’ explained Julia. ‘I did put a stove and a kettle in after a friend pointed this out, but there’s a lot of ironing. I love that you embroider all the things you will need to get you through life, such as your marriage clothes, and that they all just stayed in this space until maybe they became dowry and moved with you to another house – a space full of textiles.’

The ‘Room within a Room’ exhibition appeared at Ruthin Craft Centre last year and has also toured the Museum of the Slovak Village and the Orava Village Museum in Slovakia. Julia has had many commissions and exhibitions over the years, including from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Museum of the Romanian Peasant in Bucharest. But it is the ‘Room within a Room’ which caught the imagination of the Eisteddod judges and sees her presented with the Gold Medal for Art and Craft in Anglesey.

Eisteddfod judge Jessica Hemmings said: ‘Julia Griffiths Jones has found a way to create drawings in the air… Her way of seeing is partially familiar – we recognise the shapes of domestic objects and decorative details – but they are transformed into structural marks and cast shadows. The result feels as though a little magic is at work.’

‘I was shocked to find I had won, I suppose I didn’t know what to expect,’ said Julia. ‘It’s incredibly exciting. I know it’s hard to put what I do in a box. Someone said to me once that I’ve created my own language. Every artist wants to make their own visual language and this is mine.’