Robin Alexander welcomes Parthian’s re-issue of Janet McKenzie’s study of the life and work of Isabel Alexander, the artist whose portraits and pitscapes illuminate Parthian’s revival of the B.L.Coombes classic Miner’s Day.

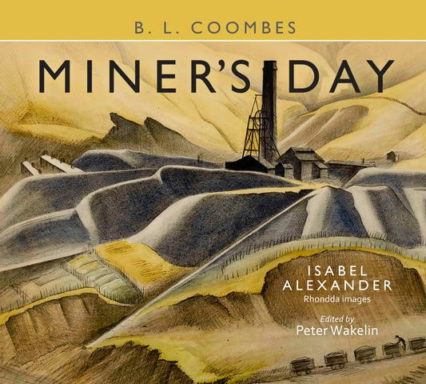

Miner’s Day first appeared in 1945 as a Penguin Special. Belying that ‘special’ status it was poorly printed on wartime economy paper and did scant justice to the lithographed illustrations that Penguin had commissioned from Isabel Alexander, the Slade-trained artist who worked in South Wales during 1943-5.

Seventy-five years later Parthian Books invited Peter Wakelin to create a second edition. Published in November 2021 to the highest production standards and reviewed here last December, this was in effect a new book. Now the Coombes text is punctuated not by those nine sadly-greying images of 1945 but by 80 in vibrant colour and the sharpest monochrome, and it is framed by Peter Wakelin’s meticulously-researched essay on the lives, times and work of both Coombes and Alexander.

So who was Isabel Alexander? What prompted her particular response to the people, places and conditions she encountered in South Wales during the war years? Where in creative terms did she head next? For apart from Miner’s Day and eight of her Rhondda portraits in the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery in Swansea – which had a wall to themselves in the gallery’s 2022 Art and Industry show – Isabel Alexander’s work is not well known in Wales.

Peter Wakelin addresses these questions as they bear on the Miner’s Day project, but in her 140-page monograph Isabel Alexander: artist and illustrator, art historian and artist Janet McKenzie is able to range more widely. McKenzie’s book was first published in 2017 to coincide with a major retrospective exhibition of Isabel’s work and with the posting of a large selection of her images in the Bridgeman online art library Now, complementing the exposure provided by Miner’s Day, Parthian has added the McKenzie book to its own list.

In her long career Isabel Alexander produced a body of work that spoke both to her changing creative preoccupations and to social conditions during the turbulent mid-twentieth century. But like many women artists of her generation she struggled for opportunity and recognition; and, like countless women now as then, she was forced to subdue creative ambition to financial pressures and the demands of parenting, and single parenting at that. Yet Janet McKenzie shows how Isabel’s skills in drawing and painting were honed by her rigorous 1930s Slade training and combined with an unflagging work ethic, fierce independence and a delight in experimentation.

Born in Birmingham in 1910, Isabel Alexander trained first at Birmingham School of Art and then, overcoming the objections of a protective father and having raised the necessary funds from teaching, at the Slade. While there she won a prize for life drawing (at that time the Slade was the only art school where women were allowed to attend life drawing classes), revelled in London’s cosmopolitan artistic life, and travelled widely in Europe. In 1939 she married Scottish documentary film director Donald Alexander, whose Tylorstown mining sequences had earned him a place on Paul Rotha’s documentary team, and who later led the National Coal Board’s film unit and became, according to Patrick Russell of the BFI, ‘arguably the key figure in the story of coal on film.’

The couple separated in 1941, propelling Isabel Alexander into a decade of financial hardship and lone parenting aggravated by the privations of the war years. Despite this, and with Rotha’s help, she managed to combine part-time teaching with work as art director on educational, medical and information films and with various book illustration commissions.

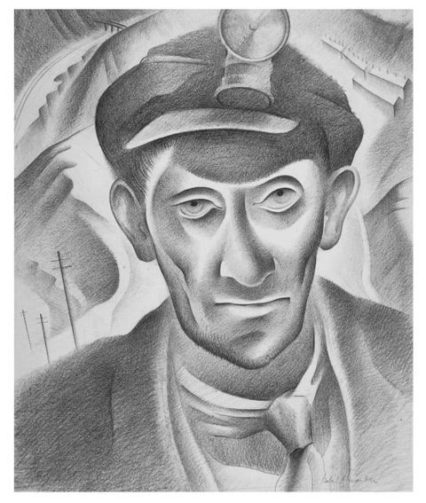

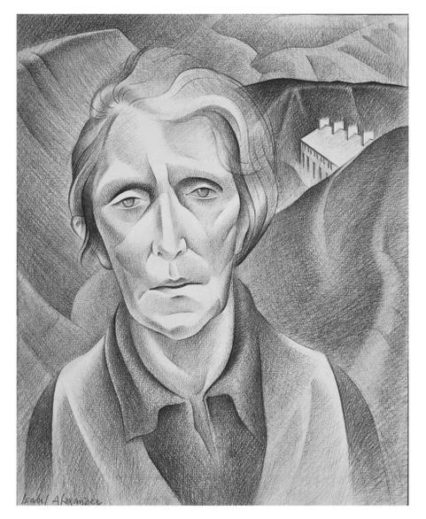

Drawing, for Isabel, was paramount, and it provided the principal medium for her response to people and conditions in the South Wales coalfield during the wartime years, a project in which she was again encouraged by Rotha and of which her contribution to the 1945 edition of Miner’s Day was one outcome among several. As to her political impetus, Coombes described Isabel in 1945 as ‘a real left winger’, and she remained so until her death in 1996, though she did not follow husband Donald into the Communist Party.

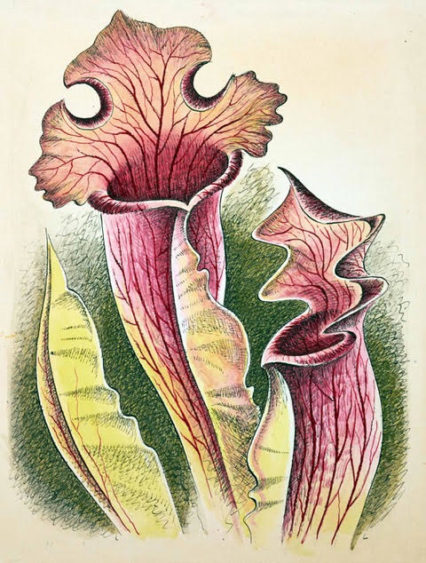

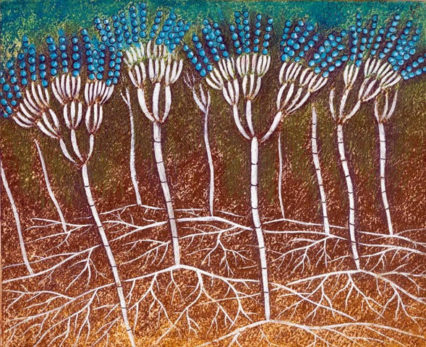

After Miner’s Day, and exploiting her considerable botanical knowledge, Isabel wrote and illustrated The Story of Plant Life for Penguin’s celebrated series of Puffin Picture Books, and then researched, wrote and lithographed its follow-up, refining her lithographic skill with the help of Barnett Freedman.

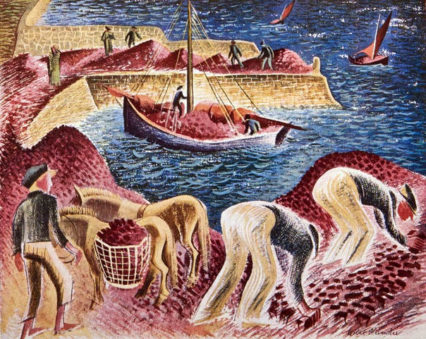

She then left for the Aran islands, off Ireland’s west coast, producing a lively series on the working lives of the islands’ crofters and fishermen.

Despite being commissioned and contracted, the Plant Life sequel, along with other Puffins by the eminent likes of Eric Ravilious, was cancelled in an abrupt change of policy by Penguin boss Allen Lane. Tantalisingly, the cancelled Plant Life sequel still exists in full mock-up, and discussions are underway about its resurrection by Design for Today. (The missing Ravilious book, White Horses, finally appeared in 2021, thanks to Design for Today’s Joe Pearson and Alice Patullo).

In 1949 and aged nearly 40, Alexander at last gained a measure of financial security when she was appointed as art education lecturer at a teacher training college. Now she could progress from work undertaken to make ends meet to a more autonomous programme of creative experimentation. She moved from her London bedsit to a small house in Thaxted, near the Essex-Suffolk border, and for a while had her own gallery nearby. Later she transferred to Yorkshire. While never forsaking line, she turned from illustration to paint, colour and form on a grander scale, and during the next forty years produced distinctive and often dramatic landscapes and seascapes interspersed by forays into abstraction. During her lifetime there were 36 public exhibitions of her work, 27 of them joint and nine solo.

Isabel travelled extensively in Britain, Ireland and continental Europe, though during the latter part of her life she spent more and more time on Scotland’s Hebridean islands. After visiting the London International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936 and Hitler’s notorious exhibition of ‘degenerate art’ in Munich the following year, she became an avid exhibition-goer, and throughout her life she retained a strong international outlook and a particular interest in European and American modernism.

The variety of Isabel Alexander’s work, and the influences she cited and quoted in her teaching booklet Sources of 20th Century Art, challenge those who have labelled her a neo-romantic on the basis of her mid-career landscapes alone. That too-easy valuation seems to have been reinforced by Thaxted’s proximity to Great Bardfield’s community of figurative artists, some of whom Isabel Alexander knew but from whom she kept her distance. Indeed she was and remained a loner, forming friendships with an eclectic mix of figures such as Cedric Morris at nearby Benton End, Barnett Freedman and Maeve Gilmore in London, and Elizabeth Rivers in Ireland; and her landscapes were bracing rather than genial or nostalgic. Then, from the 1960s onwards, landscapes melded with or were overtaken by abstraction, while during the 1980s the transient light and motion of coast, sea and sky became her passion. Yet her late paintings retain from her earlier drawings the abiding quality of movement afforded by the fluidity of line.

Perhaps as interesting as the continuities is that the powerful portraiture of Miner’s Day was seldom repeated. It reappeared briefly in her work from Aran and in her studies of farmers and farming, both of them projects of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Aran’s Kilmurvey pier is busy with crofters unloading turf for their fires. A lone figure leans into the wind at Maiden Castle, signalling not so much human contact as the ramparts’ superhuman scale. Thereafter people disappear from her canvases altogether.

For her impulses in portraying people were strongly, and perhaps necessarily, psychological and indeed political. In the faces of miners, fishermen, farmworkers, their wives and their children she registered, felt and reflected something of the lives these people led. And although in later years she was invited to produce portraits to order, she declined if the subjects didn’t ignite that spark of commitment, knowing that without it the result would be the weaker artistically. Yet commitment, even at its most intense, was always moderated, never polemical; for as Peter Wakelin notes in the Parthian Miner’s Day, ‘she drew with an objective eye as well as the humane appreciation of each individual, neither sentimental nor caricaturing’.

Isabel Alexander: artist and illustrator by Janet McKenzie is available from Parthian Books, as is Peter Wakelin’s new edition of Miner’s Day.

Robin Alexander, the artist’s son, is Fellow of Wolfson College, University of Cambridge, and Professor Emeritus at the University of Warwick.