Seen on Twitter just now: ‘I wonder what #jamesjoyce would have thought of the 140 character limit?’

What indeed? Given that Ulysses contains 264,861 words, about three times as long as the 80,000 words that many novelists content themselves with, James Joyce might take the 140-character limit with a huge dollop of salt. Alternatively he might deliberately mistake a 140-character limit as a reference to the minimum number of protagonists he should include in his next oeuvre.

It is easy to imagine that anyone beamed in from Joyce’s time, the man himself included, would instinctively dismiss both Twitter and the internet. And yet, more than likely, James Joyce would prove massively into both the web and all manner of gadgets with a lower case ‘i’ attached to them. Part of the job of a writer is to take an interest in new stuff — especially new stuff that affects writing — and figure out how to make best use of it. Proof of Joyce’s interest of new technology a century ago is the fact that in 1909 he co-founded Ireland’s first dedicated cinema, the Volta Picture Theatre, on Mary Street, Dublin. Joyce was not the world’s most tenacious businessman and the Volta struggled as bigger, more luxurious cinemas opened on Dublin’s main high street (then called Sackville Street, renamed O’Connell Street post-independence). Nonetheless, the cinema floundered on for some decades, evidence that Joyce liked to keep an eye on the next big thing, technology-wise.

But he would have other reasons for liking new reading technologies: Joyce suffered from poor vision, so developments such as voice readers and resizable text could have helped him to write and edit his books (though this would perhaps have limited the scope for intense academic debate about various editions of his work). Given his propensity to dense prose, he may even have taken the opportunity to hyperlink some of his works with their source materials, or to other parts of his own text.

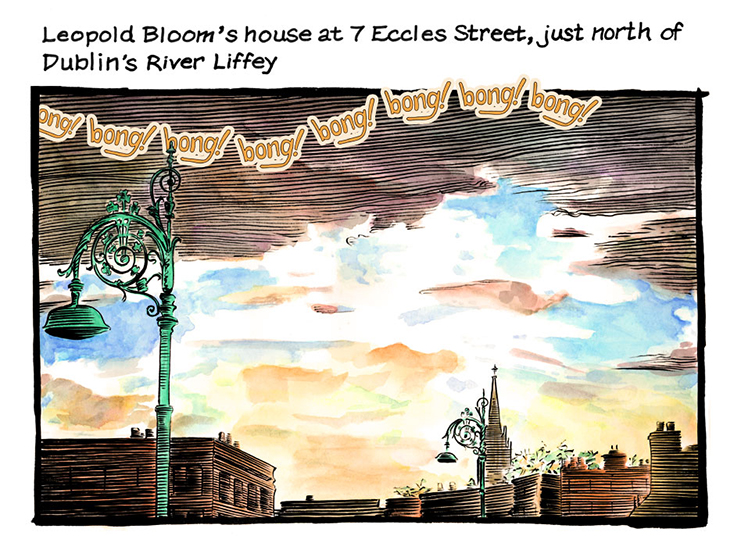

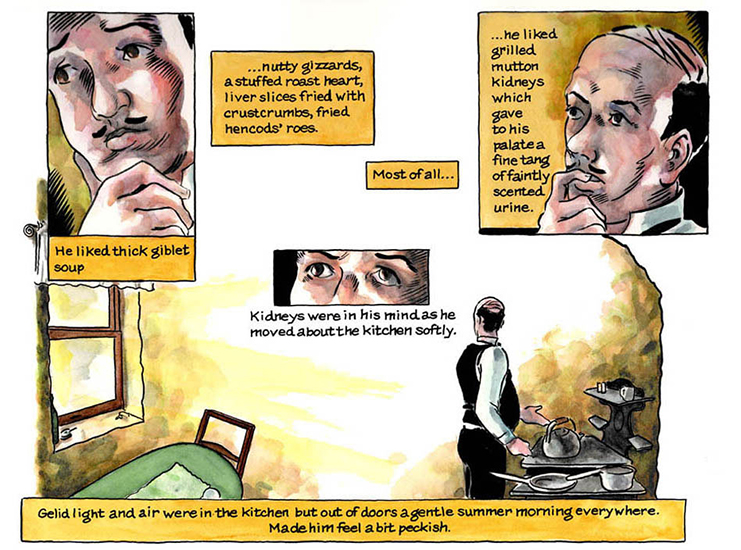

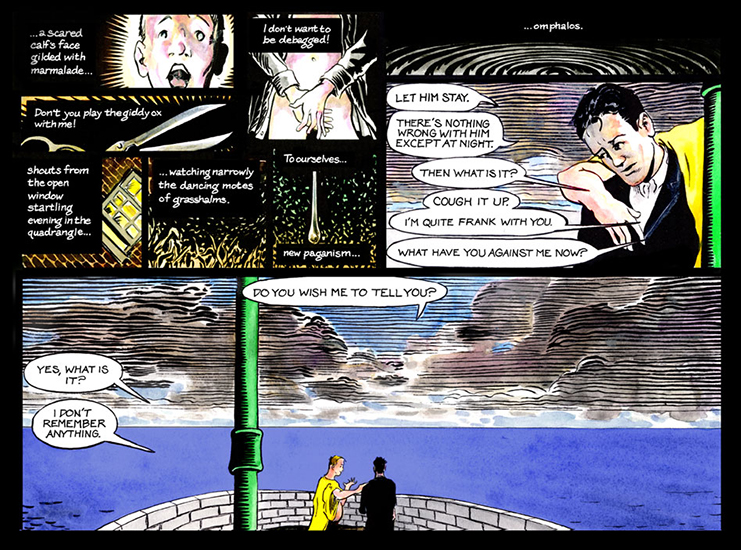

It would be fascinating to know what Joyce would make of the present level of interest in his writing, and of the role played by various new reading technologies in reinventing or reinterpreting his work. His major works are no longer restricted to actual book form, but proliferate around the world via iPhones and social media — notable among these reinventions is the iPhone graphic novel Ulysses Seen, whose pages illustrate this article, which aims to make Ulysses more accessible to contemporary audiences. It’s hard to conceive of Joyce as the kind of guy who would be uncritically appreciative of the number of Facebook likes he has garnered — but then, show me a writer who doesn’t want to see their work read. Perhaps James Joyce would say it’s a shame his slow-burn popularity did not arrive in time for him to profit by it.

Given how precarious a living he eked out (augmenting his writing income, like many writers do today, with TEFL work), it’s highly likely Joyce would have mixed feelings about his current literary success. Perhaps he might also find problematic his own adoption as a kind of avuncular national symbol in Ireland (and elsewhere). But he was always keen to see his work widely translated, and certain events early in 2013 would have been sure to please him. There were headlines around the world when it was revealed that Dai Congrong’s [partial] translation of Finnegan’s Wake into Chinese, Fennigen de Shouling Ye had become a surprise bestseller. As news of the surprise hit spread via blogs and tweets, Joyce may well have been relieved to note that his Chinese triumph was, as ever, controversial: Professor Jiang Xiaoyuan of Jiaotong University in Shanghai declared of the work: ‘Joyce must have been mentally ill to create such a novel.’

To say that the geek world has been kind to Joyce and adopted him as one of their own is an understatement. For a novel which eighty years ago was considered ‘obscene’, Ulysses has had a remarkable upward sales curve, and there can be no doubt that Joyce’s popularity online has played a part in making his works more accessible to new generations of readers.

Here are a few of James Joyce’s internet hits:

• Currently James Joyce has 163,000 YouTube results – controversial contemporary DH Lawrence lags behind at a mere 16,300

• The Wikimedia Foundation’s Wikibooks project has a page by page annotated Wikibook of Ulysses

• Ulysses Seen is a work in progress that offers a visual treatment of the scenes and chapters in Ulysses, plus annotations to the text and the chance to add your own comments

• Other graphic interpretations of Joyce’s writing are the boxed sets of illustrations Ulysses the Manual and The Bloomsday Survival Kit — OK, boxed sets may sound old media, but are very geeky if sold via an etsy shop

• Back in 2004, when Google Doodles were still a relatively new thing, a Bloomsday centenary doodle featuring James Joyce as the letter ‘g’ was released

The proliferation of Bloomsday events around the world certainly does its bit to keep Ulysses alive, taking the book off the page (be it paper or digital) and into people’s lives. Events in 2013 include a ‘Bloomsday Bathe on the Beach’ at Fuengirola Beach in Spain, a reading in Croatian, English and Turkish at University of Pula, Croatia, and all day Joycean Breakfast with nutty gizzards, liver and kidneys at the James Joyce House of the Dead in Dublin.

For those who can only tune in online, there is the Global Bloomsday Gathering a live reading of Ulysses in twenty-five cities over thirty hours, with the Welsh leg being held at Bangor.

So yeah, all in all, if James Joyce could be brought back to life for the day on 16 June, how on earth would he react to all this? Somehow, I get the impression that while he’d be pleased to see it all happening, he would give the Joycean hoo-hah at most half of his attention because he would be busy destruction-testing his new iPad (in a James Joyce case, of course) and figuring out how to make his own new iPad app of Finnegan’s Wake before someone else got in on the act.

Lane Ashfeldt is an Irish writer and the author of SaltWater, a book of stories. Following a small limited edition in 2013, SaltWater will be published in 2014. www.ashfeldt.com

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis