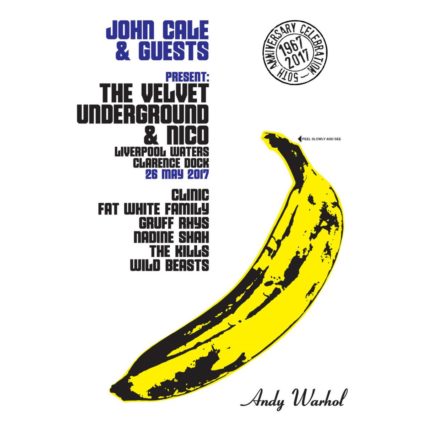

In the week of the atrocity in Manchester Craig Austin visits Liverpool Sound City to witness John Cale’s reimagination of The Velvet Underground’s debut album and a powerful display of civic solidarity.

The cocky ket-wigged kids of Liverpool mill about sunny urban streets in t-shirts that act as a reassuring crash-course in the cultural DNA of their city: Beefheart, Floyd, Love, and – inevitably – the only fruit in the bowl that entices you to ‘peel slowly and see’.

I join these kids and an array of intermittently recognisable Scouse peacocks – because shows such as this always act as a rallying point for the city’s established heads and faces – as we are ushered into Sound City’s temporary waterside venue by a series of burly men in high visibility jackets. Atypically, these men are smiling at us and exchanging good-natured pleasantries as they pat down our arms and prod around in our bags.

Their uncharacteristically cheery demeanour is not inspired by the prospect of a 20-minute version of ‘Sister Ray’ or the opportunity to witness a rare performance of timeless New York experimental rock. Instead what we are experiencing is an instinctive and heartfelt display of innate humanity forged in the fierce heat and acrid smoke of the horror.

Moments before 10pm we will stand together in perfectly observed silence as this city channels thoughts of love, solidarity and gritty defiance down the East Lancs Road and up a long-reviled ship canal; means of passage that have traditionally acted as a civic exchange mechanism for mutual enmity and outbreaks of tribal hostility. Not even the incongruous – and jarringly un-Scouse – display of union flags that fleetingly flank the stage can detract from this singularly special act of urban brother and sisterhood. A collective hush that says both ‘we honour and remember you’, and in its concluding release of raucous human emotion: ‘fuck this shit’.

The city of Liverpool has far more in common with the city of Manchester than it would openly admit; certainly more than it does with London, the city that so many post-industrial northern cities seek to blindly replicate via the latest uninspired glass and steel architectural folly. Instead Liverpool gazes west, not south; across the Atlantic and out to the historic edifices of Gotham that mirror so many of those that skirt the banks of the River Mersey.

The city of Liverpool has far more in common with the city of Manchester than it would openly admit; certainly more than it does with London, the city that so many post-industrial northern cities seek to blindly replicate via the latest uninspired glass and steel architectural folly. Instead Liverpool gazes west, not south; across the Atlantic and out to the historic edifices of Gotham that mirror so many of those that skirt the banks of the River Mersey.

It’s for this reason, and no doubt the city’s resolutely unapologetic archness, that John Cale has opted for the dockside setting of the People’s Republic rather than the lofty environs of an Albert or a Festival Hall to stage his 50th anniversary ‘reimagining’ – and the only European performance – of 1967’s The Velvet Underground and Nico; an album that continues to act as the primary set text for any self-respecting suburban outsider. Cale knows y’know.

In the true spirit of VU – intentionally or otherwise – this is a loose and at times chaotic show that both strides and stutters its way through ‘the banana album’ with varying degrees of success. Cale, with a view to injecting the required degree of pace into proceedings, displays no respect for anything as gauche as a conventional running order, tearing from the off into an electro-driven ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’ and the pounding (1968 track) ‘White Light/White Heat’.

Cale and his collection of collaborators which includes the likes of The Kills, Fat White Family and Wild Beasts are not aided by a feeble sound-system that appears to most acutely frustrate the expectations of the audience’s older members whose desire to bathe themselves in sonic excess is equalled only by a vocal cynicism about health and safety ‘going mad’. Sporadically, sound drifts off towards the Wirral Peninsula, the songs that once regaled the aloof patrons of compact New York clubs struggling to hold their own within the expanse of this large industrial setting.

Nadine Shah’s masterful take on ‘Femme Fatale’ – a song that Lana Del Rey performs frequently in this writer’s daydreams – is a particular highlight however, a commanding and imperious interpretation of its Teutonic source material. Cale’s collaboration with fellow Welshman Gruff Rhys on ‘Black Angel’s Death Song’ is perhaps the performance that most defines the attitude and ethos of The Velvet Underground though, its disconcerting video images acting as the perfect accompaniment to a set of discordant strings and electronic loops that might as well rush right up into your face and scream ‘ART!’ Rhys gets additional bonus points for wearing an extremely heavy winter coat on a swelteringly hot night (for which later he will surely not feel the benefit).

The aforementioned ‘Sister Ray’ resolves matters in a deliriously elongated and eccentric way that sees Cale and his returning charges given full reign to bust through both the framework of its recorded template and – evidently – the venue’s curfew. The less committed sections of the audience begin to peel away before its tumultuous conclusion, heading home to the embrace of their friends and families. Many clutching souvenir t-shirts and bags, all holding on to an abiding sense of communion and a shared sense of purpose; the escapist and ultimately healing power of popular music and outsider art.

The night may be drawing in but I’m beginning to see the light.