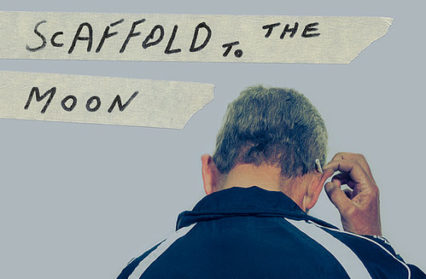

Award-winning poet Jonathan Edwards recounts his personal relationship to the poetry of Tôpher Mills to mark the release of Sex on Toast: Selected Poems, a collection curated from Mills’ best-known work as well as new and uncollected material.

I’ve met Tôpher Mills three times, and on two of these occasions Tôpher himself wasn’t even there. Such is the mercurial nature of the man, his big personality and big heart, the way the power of his printed and spoken poems stretches out beyond him and takes us by the hand or, sometimes, by the throat. So I hope it will be for readers with the poems of Sex on Toast, Tôpher’s career-spanning volume of selected poems, launching this autumn with Parthian.

The first time I met Tôpher was when I was in university, and just really discovering poetry for the first time. I’d taken one of my fledgling drafts – a poem written from the point-of-view of a sheep – to my tutor for advice. Here, he said, handing me a signed copy of one of Tôpher’s pamphlets, read this. I did, and it was great, and I had a new poetry hero to line up alongside Paul Durcan and Geoff Hattersley, Carol Ann Duffy and Patrick Jones, to inspire, guide and energise my early scribbling.

The second time was at Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff, that palace to culture in our capital city. I’d gone there to wail some poems at the populace, and Tôpher was there. We had a conversation about Tôpher’s recent experiences of caring for his mum, and I was to be reminded of this when I came to do some editorial work on Sex on Toast a couple of years later. Tôpher is a great poet of the family, and poems like ‘Apron,’ ‘Not Waving But Capsizing’ and the especially important ‘Walkabout,’ are at the heart of this great collection.

The third time I met Tôpher was another time he wasn’t in the room: on this occasion he was on the other side of a screen, on a Zoom call during lockdown. We were meeting to discuss Sex on Toast, its ins and its outs, the arrangement of poems, the placement of apostrophes. We did some of that, but we spent more of the time chatting about life and about poetry. I laughed more in an hour than I did in the rest of lockdown put together: even talking to Tôpher through a screen, you can’t help but find yourself sitting in a Cardiff pub with him, sipping half a dark, his big warm personality smashing through.

I start this piece not with the poems but with the poet because, when I think of Sex on Toast, I think of Whitman’s lines from ‘So Long!’: ‘Camerado, this is no book,/Who touches this touches a man.’ Part of the power of the poems in Sex on Toast is their great authenticity and honesty, the sense here of a full and lived life. As Whitman says elsewhere, ‘I contain multitudes,’ and so these poems branch out in so many directions, open out their arms, are copious. Family, work, romantic love, the literary scene in Wales, are all treated in such a compelling way. And importantly, these themes are dealt with through a rich variety of approaches – dialect poems and linguistic experiments nudge up against descriptions and narratives – so we are both interested to see how a theme develops across poems, and fascinated to see the new way in which it will be attacked next.

Tôpher’s commitment to dialect poetry, in poems like ‘Nevuh Fuhget Yuh Kaairdiff’ and ‘Reemaaaarrkaaabul’ is an important part of the achievement of his writing, and connects his work to vernacular poetry from Wales and beyond. Northern Irish poets like Tom Paulin and Alan Gillis gain much of the energy, urgency and personality of their writing from dunking their heads in the vernacular, while a Scottish poet like Don Paterson will place a poem in Scots on a facing page to a poem written in language which approximates the Queen’s English. In Wales, our utterly gorgeous sing-song voices are central to our identity, sense of humour, relationships and everyday interactions. More than this, the choice of dialect as a language for poetry has all sorts of political as well as human ramifications. The vernacular poems in Sex on Toast proudly take their place in the important group of vernacular poems from Wales which includes those by Mike Jenkins, David Hughes, Gemma June Howell and Stephen Knight, and which was celebrated in the recent Radio Four programme Tongue and Talk.

The spoken energy of Tôpher’s poems is important, because no discussion of his work would be complete without reference to his legendary performances of poetry, including the performances staged with that other passionate and great force for good in Welsh poetry, Ifor Thomas. Stories abound of poems performed by faces wrapped in clingfilm, of rhymes bellowed to the background music of a working chainsaw. Tôpher’s poem ‘The Parthians Invade Hay’ wonderfully captures the raucous energy of these times, while the closing image of ‘After the Festival’ describes the experience of leaving a literary festival as a ‘roller coaster down to a duller world.’ My dearest wish for Sex on Toast is that it unleashes again Tôpher’s work on the festival scene. These are poems that need to be heard as well as read, and I’m so looking forward to the performances of these poems that will set poetry in Wales on fire.

Just as I started this piece with three meetings with Tôpher, so I’d like to end it with three meetings with his poems, three possible roads through Sex on Toast. Tôpher is, firstly, a brilliant poet of work and of the realities of a working-class experience – an area of life which poetry often turns its back on. Just as, in ‘Pied Beauty,’ Gerard Manley Hopkins praises ‘all trades, their gear and tackle and trim,’ so the poems of Sex on Toast frequently give us life in what the poem ‘Blatant’ describes as ‘Thatcher’s paradise’ – an 80s and 90s world of the dole queue, the training scheme, and menial jobs. The scenarios in important poems like ‘A Scheme for Life,’ ‘Park Place’ and the ambitious sequence ‘The Factory’ will be familiar to anyone who’s seen the scene in the film of Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting, where Spud attempts to throw a job interview while buzzing on speed. Tôpher’s poems give us all the catch-22s of a working-class existence in the 80s and 90s, with a lived authenticity, the situation faced with humour as well as anger. In this sense, they take their place in a Welsh poetry of working-class social realism which stretches back to the early twentieth-century lodging house poems of W.H. Davies.

Secondly, Tôpher is an honest and tender chronicler of the vicissitudes of romantic relationships, particularly in the sustained and powerful fourth section of the book, ‘Something’s Awry’. In poems like ‘Afterward 2.25am,’ ‘Slipping’ and ‘Request’, the writing is now funny, now sensitive, now beautiful, always real. These are poems where a lover walks through a lonely early-hours urban street, nursing a wounded heart, but they are also in touch with the daftness of romance. ‘Slipping,’ in particular, with its image of two leftover bananas and a damaged bed-settee, gives us the quiddity of a late twentieth-century relationship in a way that’s idiosyncratic, resonant and memorable.

This leads me to a final route through the poems of Sex on Toast – a route that might be best navigated perhaps by readers who are willing to have a go at skiing down a road on the smooth, shiny soles of a pair of new brogues. Tôpher’s poetry is often wonderfully interested in the surreal, the comic, the extravagant image. This is poetry that lets us watch a man flying a Spitfire under Clifton Suspension Bridge, lets us see the pilot’s ‘smiling wave’ as he rushes past. It’s a poem where, on the day of the Royal Wedding, a couple make love on the roof of a skyscraper, as a crowd lines the streets below them and a pair of knickers ‘settle/on the aerial of the Prince and Princess’s black limousine.’ And it’s poetry where, in ‘Brogues, Circa 1971,’ the speaker finds himself running for a bus in brand new brogues, his hand caught up ‘between rail and bus doorway’ and, as he’s pulled along, is ‘amazed to find/the shiny solid black brogues are skidding/sliding over the road beneath them and me/performing like a perverse version of skis.’

At the end of this great poem, ‘New leather soles are scored and worn down/by the friction of my life sustained at speed/of failing and yet still getting away with it.’ Sex on Toast very much gives us a high-velocity life, with so much crammed into it. But Tôpher has done more than get away with it: he’s brought back for us a significant body of emotive, powerful, funny, memorable, singing work. I very much hope that these poems will be as important and inspirational for every reader as they’ve been for me, and I’d like to finish here by offering a significant thought to the education system. Universities of the world, keep Sex on Toast on your shelves! You never know what might happen, when some young fellow comes stumbling through the doorway, excited and bewildered by poetry, looking for a way through. You never know what you might be handing him, when you hand him this book.

Sex on Toast: Selected Poems is available via Parthian.

Tôpher Mills Tôpher Mills Tôpher Mills Tôpher Mills Tôpher Mills Tôpher Mills Tôpher Mills