David Greenslade, with the help of Keith Bayliss and Dagmar Stepankova, remembers the life of poet Josef Janda and his close connection with Wales.

Josef Janda was born in 1950 and grew up in the industrial city of Pribram, forty miles south of Prague. He completed his education at Pribram Technical School of Mechanical Engineering and worked in various capacities as a technical engineer all his life. Growing up he witnessed the mining of uranium at Pribram, the erection of a forced labour camp for political prisoners as well as the vagaries of communist education, all of which find their way into the more caustic aspects of his poetry.

Janda’s work is known for its very dark, folk-informed, wildly humorous, surrealistic, political content. Prior to the political changes of 1989 Janda was a samizdat literary nuisance, unable to publish his work via any official outlets. His poetry came to the attention of critics, artists and writers by word of mouth. As well as poetry he wrote essays and arts journalism.

Between 1970 and 1982 he played keyboards for various underground rock bands most notably Jasná Páka, banned by the Communist Party at the time. He became a member of the Czechoslovak Surrealist Group in 1984. Following the political and cultural changes of the early 90s his work appeared in Literární Noviny, Romboid, Analagon, and other magazines, bringing him wider attention. In 1994 a collection of his poems, Tapír a Pušku, ((The Tapir and The Gun, which is a very clever pun in Czech) was published by Revue Analagon. Other books followed. One, “Lakonická sdělení” (Laconic Intimations) was originally published in the September 4, 1997, as a literary supplement to the Czech daily paper, Pravo. In 2014 he received The Czech Literary Award for his contribution to poetry.

Josef Janda never married and is survived by his sister. Earlier in 2021 he had a gallbladder operation and was diagnosed with cancer which led to other complications. He died at his flat, in Prague, September 2021.

Janda’s Connection to Wales

It’s the early ‘90s and, against tough competition, Swansea has been selected to host the 1995 European Year of Literature. Visual artist Keith Bayliss is based at the Glynn Vivian art gallery working as the city’s Community Arts Officer. Keith has recruited Canadian William McClure Brown (painter) and poet Malcolm Parr to join him delivering arts and literature workshops in the Swansea Valley. This project, started in 1992, involving five schools, was called Image and Word. As part of the European Arts Festival, it was originally conceived as being confined to the locality. Under Brown’s influence however it quickly expanded and later fed into the European Year of Literature.

Brown, who painted at his own studio near Maesteg, in cooperation with Johannes Glaw, Director of Gütersloh City Museum, was also delivering workshops in Germany. While in Gütersloh he met a remarkable poet from Prague, Josef Janda. Janda and Brown had previously connected via their involvement in mail art, but in Gütersloh they met face to face.

Back in Wales, Brown tells Bayliss who invites Josef Janda to visit Swansea and participate in the Year of Literature. Janda’s arrival set the foundation for Bayliss’ and Swansea’s subsequent close and dynamic relationship with a collective known as The Group of Czech-Slovak Surrealists.

1995, a late-night phone call out of the blue.

“Are you Keith Bayliss?”

“Yes?”

“Have you asked Josef Janda to read his work in Wales?”

“Yes!”

“Do you realise he is a serious poet?”

“Well, yes!”

“He will arrive by bus. You will recognise him. He is distinctive. He will look like a mix of a young Fagin and Serpico, you know that character, in the film, played by Al Pacino?”

“OK? And who are you?”

“A friend. A Surrealist. You don’t know me!”

A few days later: another phone call, this time from immigration at London Heathrow.

“We have a Josef Janda, claiming to be a poet, on his way to Wales? Can you verify this is true?”

“Yes”

“And will you be responsible for his time in this country?”

“Yes!”

Janda arrived late at night on a crowded bus. Parr and Bayliss met him. He was not hard to recognise. Keith records that:

“Janda carried with him in his quiet, sometimes, gruff, bemused, introverted and even dismissive demeanour, an air of mystery, little was revealed, nothing truly explained.”

He had come to take part in what was now called The Visual Word. Glaw and Janda contribute along with Bayliss himself, Malcolm Parr, Tony Goble, Nigel Jenkins, Paul Henry, Anthony Evans, Marten Post, Iwan Llwyd, William Brown, Peter Finch, J.C. Evans, Paul Peter Piech, John Beynon, Lynne Bebb, David Thomas, Herve Constant, Gary Willis and – from France, Lucien Suel, from Germany, Josef Huercamp, from Russia Serge Segay.

That is how one of the Czech Republic’s most remarkable contemporary poets started his relationship with Wales. His readings in Swansea and Cardiff brought the house down.

In his foreword to Free Style, the only English language selection of Janda’s work (published in Wales by Dark Windows Press), critic Bruno Solarik recalls:

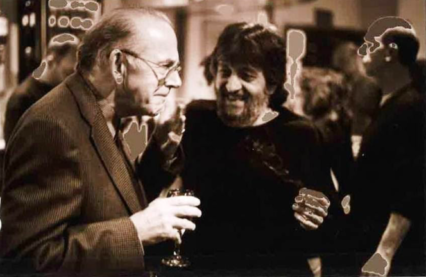

In April 2013, I was at a poetry reading for the opening of an exhibition of The Group of Czech-Slovak Surrealists, in Brussels. There Josef Janda had to face the toughest competition one can imagine. The other person who read his poems that night was no less than the world-famous artist Jan Svankmajer, a friend of Janda’s. Despite the fact that the audience – entering the large hall of the Nova Cinema – did not have the faintest idea there existed a poet bearing the name Josef Janda, a miracle happened. During the reading it was impossible to tell which of the two received more enthusiastic rounds of applause. A similarly warm reception was given to Janda’s poetry by audiences during previous readings in Swansea and Cardiff.

The Welsh readings were well attended and in response, in 1996, Janda organised an exhibition for Brown and Bayliss, with Malcolm Parr, at the prestigious Vyserhad Gallery in Prague. Janda introduced them to some of the leading surrealist artists of the day including Jan and Eva Svankmajer, Martin Stejskal, Ludwig Svab, Bruno Solarik and František Dryje (editors of the catalogue Other Air) as well as translators Jitka Machackova and Dagmar Stepankova.

These meetings led to ‘Invention, Imagination, Interpretation’, the major Czech Slovak exhibition in Swansea, 1998. The Glynn Vivian Art Gallery was the main venue with other work shown at Swansea Arts Workshop (later named The Mission Gallery), The Dylan Tomas centre and Taliesin Arts Centre showing Svankmajer’s films.

This was when Malcolm Parr, Dagmar Stepankova and myself started working on translations of Janda’s writing as a team. The book, Free Style, that eventually appeared in Wales in 2015 was finished with the poet’s participation.

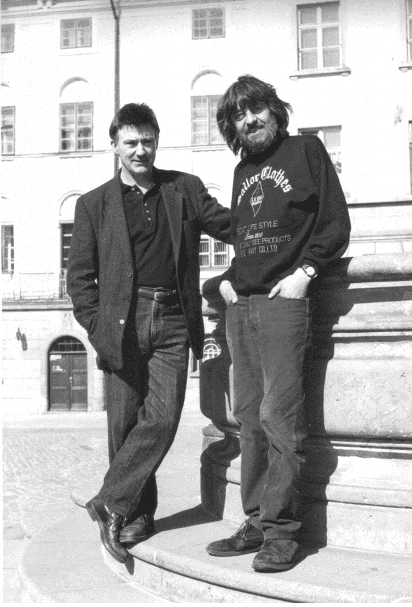

Spending time with a writer whose language you don’t speak but whose work you hope to help translate is always a great help. Between 1998 and 2013 I met Josef many times, almost always in a pub but most memorably perhaps in Olomouc, Czech Republic, in 2002.

This was another event coordinated by Keith Bayliss, taking the work of Welsh artists to Czech audiences. Janda, along with Jaroslav Mykisa, a Czech artist then living in Swansea, played an essential role. Janda and I read together and had a thoroughly good time.

S4C took an interest and Josef next arranged to bring the art of Ivan Bukovský and Lubomír Pešek to the (then) Dylan Thomas Centre. Pesek was a trained magician and this added greatly to the surrealistic pranks characteristic of this friendship.

Josef Janda’s reading style was hypnotic. His voice deep, gravelly and very rough from heavy smoking. At the end of a poem he would made a kind of concluding bark, a quiet but audible exhalation that showed the text was finished. This in itself was compelling. When the translation came an audience would eagerly expect more of the Janda voice itself, his rare, unusual grin, a flourish showing how he connected with the words. His visits to Wales often took him onto Leeds and London where he is held in great affection by the surrealist groups still active there. But the main UK events were always in Wales.

Here is his poem Pictures from Wales from the collection Free Style (Dark Windows Press):

Pictures from Wales

Josef Janda

I visited Swansea again

And I stayed with Jaro in Mumbles.

We went to The White Rose for beer.

He said things were getting better and better

even their priest recently hanged himself in church.

We visited Carmarthen

where this wizard Merlin is said to come from.

This is where, for a change, a friend of ours lives – Roger, the

sculptor

and where the smallest pub in Wales is.

It is really so tiny

that patrons drink their beer from test tubes – standing –

otherwise they wouldn’t fit in.

We chatted

and so I learnt among other things

that an elephant had died in the circus

which caught my attention and I asked

whether they organized a decent Christian funeral

appropriate for a British elephant.

“Of course,” said Gareth, and we went on to The Three

Salmons.

Translated by Dagmar Stepankova & David Greenslade