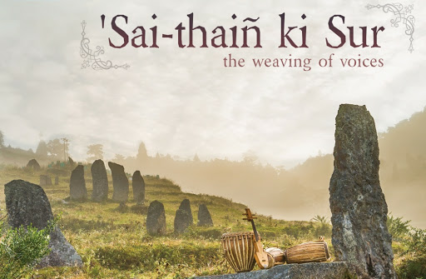

Chris Deliso reviews a unique new album from the Khasi-Cymru Collective. Grown from the seedlings of an academic project, Sai-thaiñ ki Sur (the weaving of voices) explores the little-known history of Wales and the Khasi Hills of northeast India. The project was led by Welsh singer-songwriter Gareth Bonello (The Gentle Good), who spent more than three years in the busy Meghalaya capital of Shillong meeting an array of people vital to the personal and cultural exploration of this album’s construction.

World music is full of random encounters between artists from different cultures, brought together haphazardly and having little if any prior relationship. Such is not the case with Khasi-Cymru Collective’s lovely new album, ‘Sai-thaiñ ki Sur (‘The Weaving of Voices’). Although experimental in spirit and production, it is a well-planned and well-executed cooperative musical adventure which opens a window to a now somewhat forgotten common experience in Welsh-Indian history.

Between 1841 and 1969, successive generations of Welsh Calvinistic Methodists created and maintained the first Welsh Overseas Mission, ministering to the indigenous Khasi and Jaiñtia peoples of Meghalaya state in Northeast India, then becoming a part of the British Empire. Having experienced the suppression of their own native language and culture by that same empire, the Welsh were arguably somewhat more sensitive to the locals than other Western missionaries (and definitely more so than were the colonial administrators and men of commerce). In the Khasi Hills, the Welsh mission focussed on improving literacy, education, and healthcare, but inevitably did impact traditional Khasi culture – sparking a reaction in 1899, with the creation of the Seng Khasi movement that sought to preserve traditional Khasi culture.

Nevertheless, on balance, the Welsh missionaries also did a great deal of good for bettering the lives of the locals – even standing up for their interests on occasion against the all-powerful East India Company. The work of the missionaries greatly affected the development of Khasi literary culture, and achieved its main goal of evangelisation; indeed, today, 85% of Khasis are Christian (most, Presbyterian or Catholic). The remaining minority follows the pre-existing indigenous belief system, Ka Niam Khasi, which retains its influence in the day-to-day life of all Khasis.

That said, there is sure to be enormous context behind any musical interaction between Welsh and Khasi musicians. Yet, while this historic aspect indeed underpins the new Khasi-Cymru Collective album, any prior awareness of it is not required for the regular listener to derive enjoyment from the musical experience. Vitally, ‘Sai-thaiñ ki Sur’ stands on its own merits as a unique and deeply rewarding body of work.

The overall project, which also included a theatrical performance entitled ‘Performing Journeys’ that toured in both Wales and India, was led by Welsh guitarist and songwriter Gareth Bonello, who in 2016 began work on it as a PhD student in Music and Performance, under the supervision of University of South Wales Professor Lisa Lewis. Even by that time, Bonello was already a critically acclaimed musician, having won the 2014 Welsh Language Album of the Year award for Y Bardd Anfarwol (The Immortal Bard). Then, in 2017, Bonello’s follow-up album Ruins/Adfeilion won the Welsh Music Prize.

From 2016, Bonello and his Welsh colleagues made several visits to the Khasi Hills, with the bulk of the recordings being made there in 2018. His experiences included jam sessions in remote mountain villages and buying a handmade traditional Duitara (a four-string instrument similar to a guitar) from a local master craftsman. Indeed, despite its Indian provenance, the instrument yields up a surprisingly Celtic tone on the album’s deceptively simple opening Duitara duet between Bonello and composer Risingbor Kurkalang, ‘Mei Mariang’— a song of crisply interwoven runs, as humble as any bygone Welsh missionary might have been.

In an exclusive interview, Bonello shared with me some insights into the philosophy behind the album, the recording process and the instruments used. For example, while the casual listener might be bemused by the lack of Sitars or Tablas on an Indian-flavoured album, Bonello reminds me that the project’s focus is on the Khasi people, indigenous to Northeast India, something particularly reflected by ‘the unique instrumentation and language of the Khasi community.’

Intriguingly, Bonello adds, the Khasi language and culture are actually ‘more closely related to Southeast Asian cultures found in (for example) Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand.’ This means that traditional Khasi music ‘is closer to Southeast Asian Folk Music as opposed to the classical Indian tradition,’ Bonello continues. ‘That’s not to say that the Sitar, Tabla etc. haven’t had an influence on Khasi music — they have, but Khasi musicians are very aware that these instruments are not originally from Khasi culture, whereas the percussion, Tangmuri, Maryngod and the Duitara are considered indigenous instruments.’ In the big picture, he emphasises, ‘Northeast India is extremely diverse in terms of languages and cultures, with many different indigenous groups that have influenced one another over thousands of years.’

The album’s soothing fourth track, an original Khasi folk song called ‘Ka Sit Tula’, makes fine use again of the two-Duitara approach, with the lazy strains of the Maryngod (or, ‘Khasi violin’) perfectly blending with the vocals of Duitara player Jewell Syngkli. The album’s sixth track, ‘Pahambir’ (named for the eponymous village) best exemplifies the use of various traditional instruments. The live recording, which includes various residents supporting on percussion, features Prit Makri on Muiñ (a Khasi bamboo instrument, played with the mouth) and Rani Maring on Tangmuri (a high-pitched reeded woodwind instrument). With thumping drums and an undertone of what almost resembles croaking frogs, this is definitely the album’s most ‘Eastern’ track.

Other songs from the Khasi-Cymru Collective aspire to more complex points of intersection, with mixed results. Track 11, ‘Soso & Waldo’, sees Bonello impressively backing his refined vocals on guitar, Duitara and cello. While the song apparently reflects on works by Khasi poet Soso Tham and Welsh poet Waldo Williams, the context is not readily apparent, and the end result could simply be any lachrymose meditation in the Western singer-songwriter tradition. In the opposite direction, the spoken-word experiment of Khasi poet Lapdiang Syiem (‘To the Men with Hate Speech on their Lips’) strikes out against proposed marriage legislation in India, unintentionally continuing the Welsh missionaries’ concerns for social justice into a twenty-first–century Indian reincarnation.

‘The project encouraged a creative dialogue between Welsh and Khasi artists to build a better understanding of our shared history, and to build a future relationship centered around artistic collaboration,’ recounts Bonello. After beginning in 2016, travelling frequently to the region and finally graduating in 2020 with his doctorate, the Welsh musician states, ‘I am continuing to work with Khasi artists and am eager to share the work that we have been doing over the last few years. The hope is that this album will be the first step for more collaboration between Welsh and Khasi artists and the collective will grow to include more artists from both communities.’

The album also pays tribute to the Welsh-Khasi past. The second song, Welsh-language hymn ‘Pererin Wyf’, is a minor-key classic sung with haunting precision by Bonello, whose measured guitar strumming is ably backed by Risingbor Kurkalang on Duitara.

Generally, the instrumentals on this album comprise some of its best examples of the desired inter-cultural musical cooperation. Track 8, ‘Hediad Ka Likai’, is a gorgeous guitar composition written and performed by Bonello, who drops a providentially-placed harmonic to signal Benedict Hynñiewta’s arrival on the Besli (Bamboo Flute). Further, on the closing track (a Welsh traditional dance number called ‘Alawon Cenhaty’), Bonello teaches his Duitara to play the blues, slipping in some dirty bends before straightening it out for a formal finish.

A large part of the fun of the Khasi-Cymru Collective’s debut album is its rough-hewn nature. Although one song was recorded in a Welsh studio, the rest were recorded in the Khasi Hills on either quick takes or in live sessions. Throughout the record, one can hear the occasional background cough, claps from the audience (invariably, the same locals who are performing), and even the sound of birdsong. There is no overproduction here, though the sound quality is consistent overall and the record is thoroughly listenable from start to finish.

‘For me, the process of making the music was the most important thing — by playing together we were sharing our cultural traditions and contemporary artistry, and it was that process that I found fascinating,’ Bonello says. ‘Listening back to the recordings, I feel that they capture that musical conversation very well and I think that makes them fascinating, especially as we’re hearing music from two very rare and often overlooked cultures.’

Speaking of the recording process, Bonello comments: ‘It was always a rush to record as much as possible whilst I was visiting India, so I suppose there’s a spontaneity to most of the tracks as we were still adapting them and changing them each time we played. Many were recorded spontaneously — the recordings from Pahambir Village for example just happened whilst I was jamming on Duitara with the local musicians one evening.’

At the same time, Bonello concludes, there was a deeper lesson to the experience – and one that perhaps, just perhaps, owes ultimately to the interactive process begun by the Welsh missionaries 180 years ago.

‘The recordings could only happen after building trust and getting to know one another over several years,’ he acknowledges. In the post-pandemic era, it is hard enough to imagine these recent miracles of travel and musicianship as having happened; much harder still is imagining how it would have been for both the Welsh and the Khasi upon their improbable mutual introduction in the mid-nineteenth century. Through this album, at least, we can hear some of the sounds that would have accompanied that historic encounter.

Khasi-Cymru Collective

You can find out more about Sai-thaiñ ki Sur from Khasi-Cymru Collective here.

Chris Deliso is a travel author and researcher focused on Southeast Europe, with a passion for innovative music and an MPhil in Byzantine Studies (Oxford, 1999).