Venice runs rich through the artistic history of Europe. It also runs through the Williams family. An ancestor of Sir Kyffin, reveals John Hefin in his introduction to Kyffin in Venice, did well out of the riches dug from Anglesey’s Parys Mountain. The fortune it provided allowed for homes in Berkley Square -more likely London’s Berkeley Square – and Venice.

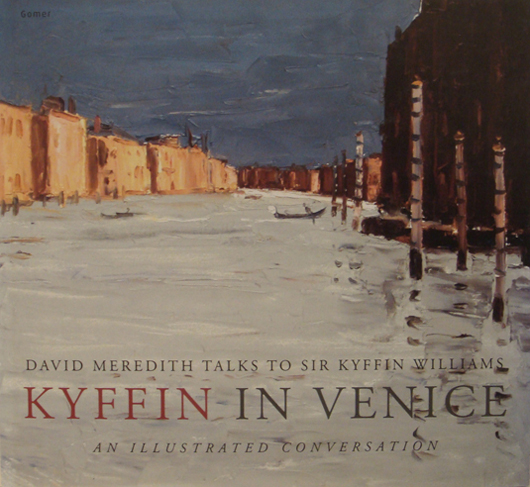

The occasion for Kyffin in Venice was a television documentary, acclaimed at the time and now archived inaccessibly. The book comprises twenty-two photographs, twenty-one paintings and a dozen drawings. The text, a transcribed conversation with David Meredith, spans biography, motivation and method, artists and art history.

David Meredith touches on Williams’ popularity. ‘Success in Wales today’ he quotes ‘means having a house in Pontcanna in Cardiff, a Volvo in the garage and a Kyffin on the wall.’ It is not a universal popularity. A prominent curator-commentator takes the view that ‘he waxed splendidly splenetic in defence of his time-locked, academic church and was implacably against anything he construed as “modern art”… He became something of a predictable rent-a-quote in his railings… did much damage… feeding the tendency of the philistine press to ridicule developments in contemporary art.’

by David Meredith

Gomer 2006, 84pp

Williams in conversation gives as good as he gets ‘art is in such a terrible place… there’s a very conscious attempt by evil-minded people to destroy all tradition in art.’ The Williams work itself divides in two: on one side the rocks and skies of Wales and elsewhere and on the other the living creatures, from his inimitable sheepdogs to the horses of Patagonia and the swiftly executed portraits of worthies of Wales. Even there he met his foes. He recounts sending a photograph of his portrait of Alun Oldfield Davies, former Controller at BBC Wales. A letter in return declares: ‘We consider this picture to be repellent.’ ‘The word “repellent” struck me to be rather fierce’ says the artist.

He pinpoints the central place of Venice in painting. The invention of oil and its superiority over tempura- colour mixed with egg yolk- is crucial. Antonello met a pupil of Van Eyck in Naples, most likely Petrus Christus, who ‘gave Antonello the secret of the oil medium.’ The following year this knowledge of oil was passed on to Giovanni Bellini in Venice. Oil releases the brush so it can used with a greater swish and flourish. It makes for weather and cloud that are capable of being rendered beyond white and blue. It is the midwife for landscape painting.

The Venice that Williams depicts is done through a particular eye. It is not a place of high colour. The Alps are colourful because of the air and altitude. Down on the Venetian quayside the light has a subtlety, the sky can turn a deep blue-black, and the palazzos along the Grand Canal have a silvery aspect that was caught at its best by Francesco Guardi.

Williams traces the probable line of influence from Venice northward. Rubens was in Venice and saw the landscape backgrounds that Titian painted. Rubens painted the Chateau de Steen with Hunter, a painting bought by a collector from Norwich. There Constable must have had sight of it, he states, so that the line passes straight through to ‘The Hay Wain.’

The twelve Williams images of Venice range from sketches to full oils, the earliest a bend in the Grand Canal dating from 1962. An oil from 1979 captures St Giorgio Maggiore at sunrise, another of the same year the Giudecca as a sombre near-silhouette. For a distant view of the city his composition gives nine-tenths of the canvas over to water and sky. It is a lighter creation, a nudge towards the brilliant silvery pointillism with which William Wilkins created his Venetian views.

Meredith asks some pertinent questions about Williams’ changing method. He has evolved a technique for the effect of light hitting a hilltop. He mixes three or four colours but not completely. With strands of white, black, yellow ochre, cobalt green ‘the colours aren’t actually mixed up, each colour shows slightly in the paint and it gives a shimmer.’ He makes the contrast, modestly, with Matisse: ‘he can throw up ten colours in the air and catch them, whereas I can only throw up four balls of colour and catch them. If I tried five, I’d fall flat on my face.’

Kyffin in Venice is a slim book but a full one. It whets the appetite to see the film but the text is good enough in itself. Television is never at ease with still images. That stillness of contemplation that painting invites was understood by Werner Herzog, when he went into the caves of Chauvet, but it is often lost on the Torquils. When television took on Brenda Chamberlain it could not even represent her self-portrait in its entirety.

Williams has many interesting asides. He was model for the coat for Ivor Roberts Jones’ sculpture of Churchill. He voices his admiration for John Gibson and critiques Graham Sutherland’s version of Pembrokeshire with its oranges and lime greens. ‘They were good pictures but they were not in my mind an interpretation of the landscape. Artists very often get the wrong end of the stick.’

The story that underpins Kyffin in Venice is that an artist can be distinctively in, of, and from Wales. At the same time art is inseparable from Wales’ embeddedness in its setting, the culture of Europe as a whole. A strand of fanciful cultural critique now and then tries to lever Wales entirely out of its geographical and historical setting. A search for an ur-Celticry tries to assert that its art has more affinities with Kerala than the regions that are its actual neighbours. David Meredith does not touch on this particular topic but the forthright response of the battling Williams can be well imagined.