Jim Morphy delves into Nick Cave’s world of bootlegging in his review of Lawless, John Hillcoat’s star-studded follow-up to The Road.

‘I’ve always been interested in violence…and I think the reason I got into film in the end was that was the most effective way of dealing with that particular subject. I think that’s why movies exist, and why people continue to go along.’ A left-field take on the essence of cinema, but an interesting and valid one nonetheless. It’s also not an altogether surprising one considering it comes from the genius outlaw-artist Nick Cave, dealer in the classic Old Testament themes of murder, betrayal, revenge, and redemption.

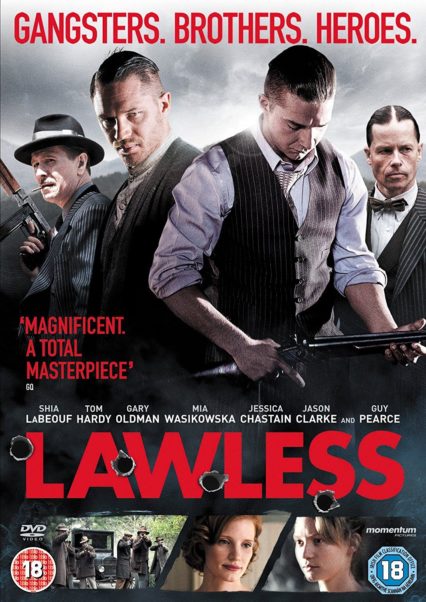

Directed by John Hillcoat

Starring: Shia LaBeouf, Tom Hardy, Guy Pearce, Jessica Chastain

Cave says it was this liking for all things fire and brimstone that first attracted fellow Australian John Hillcoat to him. The relationship began when Hillcoat edited the video for The Birthday Party’s 1981 track ‘Nick the Stripper’. More recently, Cave took scriptwriting and score duties on Hillcoat’s prison drama, Ghosts… of the Civil Dead (1988), and outback western The Proposition (the best English language film of 2005?). Cave, and Bad Seed Warren Ellis, also penned the music for Hillcoat’s recent interpretation of Cormac McCarthy’s barbaric novel The Road.

Hillcoat again turned to Cave for the words and music for his latest exploration into a world of alpha-males, the impressive gangster period-drama Lawless. The film is an adaptation of Matt Bondurant wonderful novel The Wettest Country in the World, based on the true story of his grandfather and two grand-uncles, a gang of moonshiners operating out of the hillside-woods and dirt-tracks of Prohibition-era Franklin Country, Virginia.

The story shares a set-up with The Proposition, following three brothers as they go about carrying out crime and dishing out punishment. Seriously thuggish though these characters are, our sympathies are generally very much with them. Middle brother Forrest (Tom Hardy) is the intelligent, broad-shouldered leader of the clan. Hardy – all slow movements, grunts and shrugs – puts in an audaciously restrained performance, somehow giving his character an other-worldly presence that grows in force even though he barely utters a coherent sentence. Hardy’s star is very much on the rise. Eldest brother Howard (Jason Clarke), full of demons from his time in The Great War, provides the drink-dependent muscle.

The boyish, rash, wide-eyed Jack (Shia LaBeouf) grabs most screen time, and his desire to become A Man drives the perfunctory small-town gangster plot forward. Jack tries to earn his keep in the brothers’ business by selling the whisky, with his crippled friend Cricket (Dane Dehaan) often in tow. The pair offer much-needed sweetness and humour in this sickeningly macho world. We also see Jack’s embarrassing, but successful attempts to woo Bertha (Mia Wasikowska), daughter of a local preacher man. LaBeouf does well to ensure that he, like his character, just about holds his own in this place of more immediately-impressive beasts.

Newly-appointed Special Deputy Charley Rakes (Guy Pearce) – sent from the big city to sort out the locals – offers us the necessary villain. Truly hideous-looking, impeccably dressed, forever sneering, and with serious rage and sexual ‘issues’, Rakes is a hardly-believable character, veering close to pastiche. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing in this genre where we know full well what we want, we just want to make sure we get it in spades. In fact, the story could really do with more of this magnificently-despicable creation – not least to give the impressive Pearce the opportunity to munch on a little more scenery. Gary Oldman’s cameo as Chicago gang boss Floyd Banner also leaves us wishing he had a bigger part.

Women get little of a look in here. Wasikowska and Jessica Chastain (Forrest’s love-interest) do well to eke out every drop of their flimsy roles. Concerns have often been raised about Cave’s skills in portraying women – his work is full of unattainable goddesses, fallen-on-hard-times ‘broads’ and other not-fully-rounded and stereotypical characters. Lawless – where women are generally reduced to crying in bedroom corners and running down streets, naked and screaming – offers further ammunition to the critics.

Music, however, is one area where Cave’s genius cannot be questioned. And with Ellis he has put together a stunning Appalachian-tinged soundtrack. For this the duo, playing with a variety of cohorts including Mark Lanegan, Emmylou Harris and Ralph Stanley, have recorded a mix of original music and classics from the likes of John Lee Hooker, Townes Van Zandt and Captain Beefheart. The sound in one church scene with the congregation singing – near chanting – a hymn as a demented Jack stalks Bertha is completely intoxicating. It certainly is for nervous Jack, who vomits, overcome by sensory overload.

Plaudits should also go to Director of Photography Benoît Delhomme for continuing his good work on The Proposition by offering us another visually striking film. Lawless, inevitably, builds towards a showdown between the Bondurants and Rakes, giving Jack the opportunity to earn his spurs. All ends a little too neatly, and, even, sentimentally, but a little comedown at the end will be much appreciated by many. ‘It’s not the violence that sets men apart but the distance they are prepared to go,’ Forrest tells us. And with this film, and its steady stream of beatings, knifings, shootings and testicle-stripping, Hillcoat and Cave have proved yet again that they are willing to go a pretty long way.

It remains a straighter, more by-numbers film than the scorching The Proposition, but this is a seriously strong outing, consolidating yet further Hillcoat’s and Cave’s reputations as practitioners-extraordinaire of outlaw cinema.