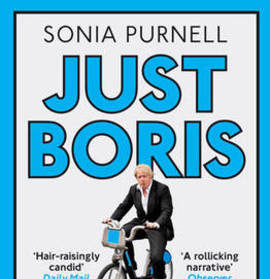

Adam Somerset rereads the last biography of the Prime Minister, Sonia Purnell’s Just Boris.

Leonard Woolf recorded a lunch that he had once had with Ramsay McDonald. The rissoles at the London club were flavourless and the conversation humdrum. McDonald, Prime Minister at the time, had travelled by train from Lossiemouth and was heading on to make an important speech to the House of Commons. When they parted, McDonald told Woolf that he had flu and a temperature of 102. This was said, recorded Woolf, “all without turning a hair, for he had an iron constitution which is the first and perhaps the only necessary qualification or asset which a man [sic] must possess if he is to become Prime Minister.”

The encounter comes to mind in a re-reading of Sonia Purnell’s biography from eight years ago. Purnell mentions that the Prime Minister of 2019 has always enjoyed remarkable and consistent good health. The era that was ignited on 23rd June 2016 is set to be pored-over and scrutinised like no other in the last decades. Just Boris will be alighted on as a first authoritative source for a guide to the life that has ensued. It is a heavyweight biography. Purnell draws on 129 interviewees, a formidable roll-call across politics, media and the personal life. These are detailed in 14 pages of notes and an index.

The title is carefully chosen. It echoes a theme that has been regular throughout the commentary over the last three years. The pursuit of power has been one without political or social conviction. Purnell’s last line reads, “until he shows that he has a real purpose for power beyond power itself, the suspicion will remain that he is in it for only one cause and for only one person: Just Boris.”

If Purnell is not admiring the observations in her book have the ring of truth. Paula Sherriff spoke in the Commons on 26th September about the death threats to herself and many other women. The instant jab back was “I have never heard such humbug.” To have watched it live was truly shocking. Purnell points to its lineage. The Johnson language was honed from the first days in the career of journalism: “gloriously old-fashioned phrases, words and humour that set him apart”.

Family is the crucible of attitude and it is unlikely that a future biographer will be able to unshift Purnell’s conclusions. Johnson, endlessly affable, has like the occupant of the White House no close friendships. It is a trait that he shares with Margaret Thatcher. “For all his quick-fire wit,” Purnell observes, “he does not really laugh.” She offers an explanation: “to laugh – as to cry – involves a loss of control, almost an admission of vulnerability and that is something he is unwilling to allow.”

She locates the quality of self-containment in childhood experience. Johnson suffered quite severe deafness until he was aged eight. The other factor is the father, the larkiness a part of the family inheritance. While working at the World Bank Stanley Johnson submitted a proposal for a $100m loan. The purpose was to build three new pyramids and a sphinx. The proposal was dated 1st April. The head of the Loan Committee, Robert McNamara, was not amused. “Stanley was forced to seek alternative employment.”

Purnell encapsulates her characterisation of Johnson Senior in a single sentence. “A serendipitous series of events in which freebies, jobs, holidays, houses, prizes and sponsorships have rained on Stanley, ensuring relative wealth even at university, and certainly thereafter. Such impossible good luck as he has experienced has had an effect on his mindset, which does not really register hardship or struggle.”

As an adjunct codes and laws- the norm for the rest of us- are there to be waived for the Johnsons. When Johnson Junior vacated his parliamentary for City Hall Johnson Senior stepped in to claim the seat as an item of family entitlement. It took David Cameron’s intervention to see him off. Stanley Johnson’s attitude to authority is illustrated on his home turf at Nethercote in Somerset. “He exults in hurtling down the narrow, winding Somerset lanes”, Purnell writes, “He and his family were well-known to the police. He used to revel in the number of times he had been stopped and let off- it was a badge of pride in a Johnson japes’ kind of way.”

This relationship with the law runs on in the son. Eton produced a criminal in the 1990s by name of Darius Guppy who was jailed for five years. In the view of our Prime Minister he was living “by his own Homeric code of honour, loyalty and revenge” and he liked his “ascetic contemplative intelligence”.

On the life in journalism another Old Etonian penned a verse in the style of Hilaire Belloc on Johnson’s departure from the Brussels press corps. “Boris told such dreadful lies/ It made one gasp and stretch one’s eyes.” That was James Landale. The mistruths started immediately. Johnson secured a front-page splash for a story he had made up at the time the Danes were voting in a referendum on the Maastricht treaty.

The Johnsons are at Eton out of cleverness not inherited wealth. A theme that runs throughout Purnell’s telling of the life is private avarice. Out of university the youthful Johnson joined a prestigious management consultancy. He was interviewed in a pair of red braces, left after a week and pocketed the joining fee. The people of London paid up £99.50 for a return taxi drive for their Mayor. The journey was a couple of miles, City Hall to Elephant and Castle, a charge that was frequent. An offer to donate part of his double salary to charity never apparently materialised.

Purnell relates the constant juggling between journalism and politics. When he took the editorship of the Spectator he told Conrad Black he had made the choice definitively between journalism and politics. Two years later he was back in Parliament, one of the Commons’ lowest participants due to his job at the Spectator. When the Foreign Secretary left the Cabinet the Barclay twins reinstated his £5000 or so a week within the week. The benefit in enhanced sales of their newspaper hugely eclipsed the cost of their star journalist.

Britain is in a unique position. Two party leaders are alike in not having a single piece of legislation to their name. Neither has a record of participation in a Select Committee. The loyalty of both to their historic parties is elastic. A party insider tells Purnell about the AV referendum April 2011. “We pleaded with him to do some high-profile events because we knew it would make a difference. He didn’t see it in his own interests.”

Neither has any great skill in holding the House. Purnell quotes Quentin Letts: “He was terrible in the chamber, an echoing parody of himself. The Commons sees through you in a way that other institutions don’t.” But Letts also pins down the Johnson-Corbyn difference. “He was trying to ventilate false anxieties about matters in which he wasn’t very interested. The reaction was quite often silence. You see Boris isn’t angry, you’ve got to be angry, you’ve got to feel things as an MP, but there’s no soul, there’s no church in him.”

And yet. Purnell ends by eliciting some sympathy for this gifted, driven, brilliant man without purpose. “Boris finds making genuine conversation with people- and particularly with professional women on an equal footing- difficult. Indeed one female assistant talks of how she dreaded car journeys with him because of the long awkward conversations. He is better at talking at people in performance-mode than talking to them.”

But when he has purpose he is unstinting in pursuit of its realisation. He challenged the Clwyd South seat and learned enough of the language to sing the national anthem and order psysgod a ysglodion.

And there is the paradox of the will to power. Greatness in politics has no overlap with goodness of human spirit. In the 2005 leadership contest between the two Davids Johnson backed his fellow Etonian over the meritocratic Davis. As he told the Press, “I am backing David Cameron’s campaign out of pure, cynical self-interest.” Johnson has torn through many a presumption of politics. Blair’s language altered according to his audience. The Prime Minister who spoke on Woman’s Hour, and impressively so, had a voice that was different from the man at the Labour Conference.

In that respect Corbyn and Johnson are alike; both are WYSIWYG as the tech guys used to say. What you see is what you get. Purnell describes it as “Boris’ calculation appears to be that we want to look up to our leaders as some superior version of ourselves- wealthier, more erudite and undoubtedly better educated.”

The politics of the United Kingdom, an asymmetrical union in its disproportionate populations, are determined by what England wants. The next 28 days will reveal whether Johnson has read his England rightly.

Adam Somerset‘s selected essays, Between the Boundaries, is available now from Parthian.