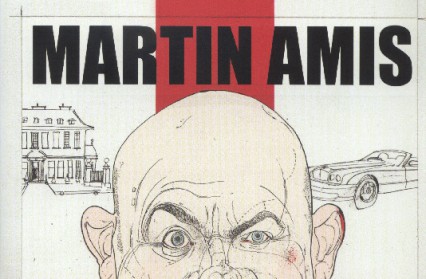

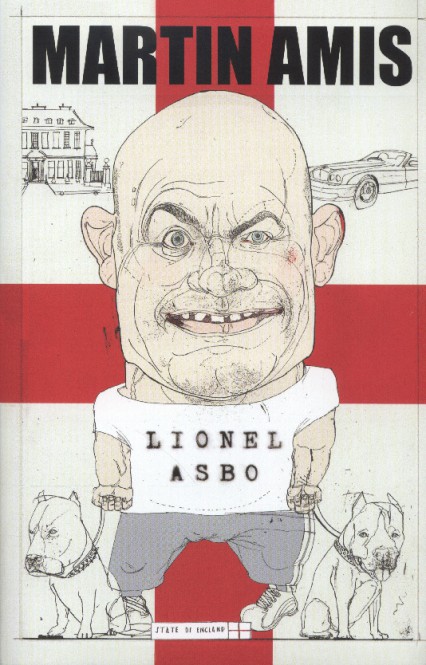

John Lavin casts a critical eye in his review of the latest humorous fiction novel by Martin Amis, Lionel Asbo: State of England.

It was about two-thirds of the way into Martin Amis’ last novel, The Pregnant Widow, shortly after a character called Gloria Beautyman has just said ‘I am a cock. And we’re very rare – girls who have cocks’ that I did what I would at one time have considered impossible. I threw a Martin Amis novel across a room, never to pick it up again. This, of course, is what his father Kingsley had famously done when the character of Martin Amis had made his way into his son’s superlative fifth novel, Money. Kingsley felt that his son was committing, in his view, the worst of all crimes; that of ‘buggering the reader about.’ But for me it was for a reason I would never have expected. It was because of the writing – the writing, no less! – of ‘the most original prose stylist of his generation’ (The Independent), was not any good. Was, though I hesitate to say it, poor. This was something new, something terminal-seeming.

While the plotting and characterisation (never in any case Amis’ strongest suit) had been at an all-time low in Yellow Dog (with a marginal improvement in the sombre, Gulag-set House of Meetings) there was still that prose style. A style that seemed to take both the prose and poetry of his father and fuse it together into one satirical yet luminously beautiful whole. But take away that style and what was left? Just imagine for a moment how awful London Fields would have been if it had been written badly. If that sounds self-defeating obvious, then think for a second about that novel’s extraordinarily convoluted and dissatisfying plot, then of its – with the exception of the fully multi-dimensional, compellingly awful Keith Talent – thin, one-dimensional character; and then think of it being written by a bad writer rather than by Martin Amis at the full height of his powers. This, sadly, was a fairly close approximation of what reading The Pregnant Widow was like.

All of which goes some way to explaining why Lionel Asbo is such an unexpected triumph. That title, for instance, immediately sounded alarm bells. It couldn’t, on first sight, sound very much more Daily Mail, or out of touch, or in keeping with the Kingsley-Esque shift to the right that Amis seemed to have been making – despite his protestations to the contrary – throughout all of that weird writing he did on 9/11 and the War on Terror (or ‘The Age of Horrorism’ as he would have us call it). Add to that the fact that it was at one point part of the same manuscript as The Pregnant Widow, before Amis realised the two strands couldn’t fit together, and you have a proposition that alarms rather more than it allures.

However, as it turns out, this final aspect may well prove to be the answer behind The Pregnant Widow’s desultory awfulness and the frankly astounding return to form that Lionel Asbo represents.

Writing recently about the composition of The Corrections, Jonathan Franzen spoke about the ‘dead’ novel he had to throw away in order to be able to write The Corrections, and it may well be that The Pregnant Widow is the novel Martin Amis had to throw away in order to write Lionel Asbo. Only he went and published his dead novel, didn’t he? Giving it an extra-portentous sub-title, ‘Inside History’, into the bargain.

Lionel Asbo has a portentous second title too: ‘State of England.’ This was also the title of an excellent Amis short story from 1996 and while that story’s central character, Big Mal, only makes a cameo appearance here – as one of Asbo’s bodyguards – we nevertheless find Amis returning to the atmosphere of that earlier work. And in doing this he somehow seems to have managed to re-find the fizz and the glee and the swagger that has been eluding him in the books he has written since his deeply moving memoir, Experience, in 2000 (a book which was so successfully executed it seemed to make Amis believe he could do ‘deeply moving’ in his novels, too. This, perhaps, is the reason for the decade long malaise).

Lionel Asbo finds Amis back in full-on, hard-nosed, garishly-satirical Money-mode. And you quickly realise that this is what he does best. That while he himself might want to reach for the weightier, apparently more profound style of his idols, Bellow and Nabokov, the style that suits him best is this. A kind of gonzo approximation of Evelyn Waugh.

Indeed the novel it most consciously echoes is Scoop, with its garish satire of contemporary culture and, indeed, contemporary journalism. He is particularly incisive about celebrity culture, perhaps because he is one of the few literary writers of the past thirty years to have received substantial tabloid attention himself. He is also brilliant at aping tabloid journalese, and never more so than in a section written in the form of an eight-page tabloid feature on Asbo and his Katie Price-like girlfriend, the improbably named ‘Threnody’:

Lotto Lummox, Raffle Rattleplate, Numbers Numskull, Pick Six P***brain, Sweepstake Psycho, Bingo Bozo, Tombola Tom O’Bedlam – the Lotto Lout’s been called the lot.

…Our nationally famous Agony Aunt, Daphne, went to Loopy Lionel’s country seat, in the once-sleepy Essex village of Short Crendon, to offer her council to the Chav S***head.

This is a book that almost always gets its jokes right. It is dedicated to Amis’s late friend Christopher Hitchens and you sense that on nearly every page. It is not clear how much of the book was finished before Hitchens passed away but you feel that Amis is trying to use the full extent of his powers (trying, in essence, to fully regain them) in order to make Hitchens laugh. There are times when the book feels like you are in the company of a dazzlingly accomplished raconteur and you can almost picture Hitchens exploding into mirth, even as he readies himself with an equally brilliant riposte. Amis expounds on everything from crime to traffic, from porn to the weather, from cats to dogs and from love to hate and somehow always gets it just right; the way that he always used to get it just right in novels like Other People and Money. Amis has spoken about the feeling of ‘responsibility’ that comes with losing such a close friend as Hitchens, the ‘responsibility’ of being the one given the privilege of more time on the planet, and of the feeling of renewed creative impetus that comes with that. Lionel Asbo, with all its youthful vigour, with all its sadness and glee, with all its impeccable, luminous prose, certainly bears testament to that.

Lionel Asbo by Martin Amis is available now.

John Lavin is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.