Nigel Jarrett attends a concert featuring Debussy, Messiaen, and Mozart from the BBC National Orchestra of Wales conducted by Jac van Steen including pianist Steven Osborne.

Aside from their importance as landmarks of the piano repertory, the two books of Preludes by Debussy are a source of encores. In the 100th anniversary year of the composer’s death, the pianist Steven Osborne chose Canope, from Book 2, as an enhancement of his appearance at this concert in a Mozart concerto. The prelude’s softly struck chords and tinkling suggest the elegiac in its echo of the gamelan, a sound from the Far East that enriched music in its ever-onward quest for the new. Osborne was thus acknowledging that Debussy pervaded this concert, even as an influence on Messiaen’s Les Offrandes Oubliées, the ethereal outer movements of which seem to suspend time itself and support the idea that the new can also burnish deep and age-old certainties.

Debussy’s kind of innovation often thrives in the most prosaic places: a mound can suggest a mountain, a stretch of water an ocean of embattled elements. Thus it was that in nowhere more primly self-restrained than Eastbourne did he complete the orchestration of the three symphonic sketches that comprise La Mer, having begun its composition in a French village, landlocked and equally uneventful.

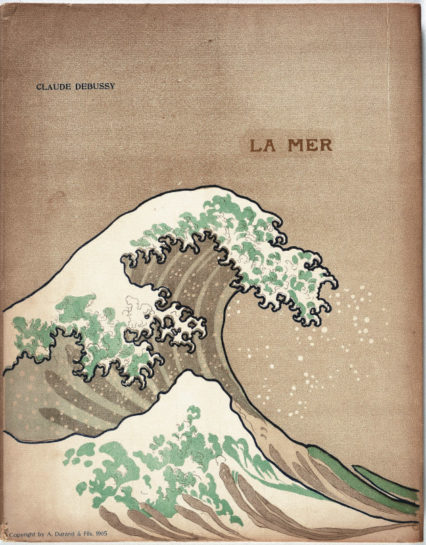

But nowhere in the programme for this concert was there a reference to the image on its cover: The Wave by Hokusai, in which a boat and its crew are about to be inundated by a colossal roller and which formed the frontispiece of the first published edition of the score. It might well have served as a pointer to how conductor Jac van Steen and the orchestra went at the turbulence; in truth, more unrestrained than painterly, for Debussy was, as the title of a new book by the musicologist and critic Stephen Walsh has it, a ‘painter in sound’.

Both the central Jeux de vagues and the final Dialogue du vent et de la mer had moments when the view was not a recollection in tranquility but a salt-sprayed experience of near-death by drowning. All exciting stuff, if unnerving for the listener. The opening of De l’aube à midi sur la mer extended the mood of Debussy’s Nocturnes, with which the concert began, and asserted van Steen’s intention to deal even-handedly with this music’s mysterious correspondences, to which the merely picturesque soon gives way; but the overall whoosh was meteorological rather than metaphysical. There are more refined and considered ways of interpreting this work, ones which better reflect the interior landscapes that for Debussy morphed from impressions of nature.

Nocturnes was begun almost in a mood of reverence akin to the ritualism of Messiaen at his most ecstatic. In Nuages, we encountered clouds that were barely moving, which is as it should be; in Fêtes, a heady carnival atmosphere interrupted not by the dazzling vision as described by the composer but by something more vaguely sinister, though any menace afoot was soon swallowed up; and in Sirènes the swing of the sea, with a female chorus of bewitchers encouraged by van Steen to make the most of their appearance rather than spin a beguiling web before passing out of sight. And how well they did that represented the quiet end of van Steen’s insistence on exploiting Debussy’s full dynamic range. This sometimes involved too stark a contrast between sonorities and too hasty a determination to advance the music, thus robbing it of more ambiguity than was desirable. That approaching march in Fêtes, for instance, was upon us before we’d had time to wonder about its provenance.

In the final movement, the women of the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama Chamber Choir excelled themselves, and were a credit to chorus-master Adrian Partington, who prepared their contribution and shared their applause. The 27 singers were located on the left flank of the platform, so were effectively part of the orchestra, their proximity a further example of how the hall’s acoustics were true to music that might sound dreamlike but is in fact concentrated and precise. In taking special applause at the end, the cor anglais player, Emily Cockbill, stood for the whole orchestra. Disparities were even bolder in the Messiaen work, the central ‘forgetting of God’, as the composer had it, as raucous as the outer movements were other-worldly.

Is there a British pianist of rank with a lighter touch than Steven Osborne? His evenness of tone and almost weightless articulation were so obvious a feature of his performance in the Mozart concerto (a late work) that it was easy for the orchestra to attune itself to his playing and respond to it with a delicacy of its own. Few in the BBC NOW today will remember the time when, as the BBC Welsh Orchestra, its smaller complement meant that works like this became staple.

Only in Mozart’s own cadenzas – with a contribution from Osborne himself on this occasion – did the music ratchet upwards to the sort of episodes that encourage some pianists to perform the whole work as though it were by Beethoven. Not that the concerto lacks emotional variety or depth. Most of all it is replete with nostalgia and plaintiveness; and, this being Mozart, these are not cocksure.

All leads to the delightful, if over-cooked, rondo, in which a simple tune is worked brilliantly to recall the elegance and profundity of a younger composer. Osborne followed its path unerringly, harvesting all its grace, nobility, and humour.

It was birthday time for the orchestra, which next month will be ninety years old. So it played an encore of its own, Debussy’s Danse, in the orchestration by Ravel. There was no reduction of the energy expended earlier; quite the opposite, as everyone seemed eager to get to the party.

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Soloist: Steven Osborne (piano)

Conductor: Jac van Steen

Debussy: La Mer; Nocturnes

Messiaen: Les Offrandes Oubliées

Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 27 in B flat (K.595)

St. David’s Hall, Cardiff, 23 March 2018

Nigel Jarrett is a winner of the Rhys Davies prize for short fiction and, in 2016, the inaugural Templar Shorts award. He’s a former daily-newspaperman and a regular contributor to the Wales Arts Review, Jazz Journal and Acumen poetry magazine, among others. He is also a poet and novelist. His latest story collection, Who Killed Emil Kreisler?, was published in 2016, as was his first novel, Slowly Burning. This year sees the publication of his short fiction pamphlet, A Gloucester Trilogy.

You might also like…

Nigel Jarrett reviews Stephen Walsh’s latest book, Debussy: A Painter in Sound which enriches both popular taste and serious scholarship.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.