St David’s Hall, Cardiff, 8 June, 2017

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Piano: Jean-Efflam Bavouzet

Conductor: Thomas Søndergård

Prokofiev: Scythian Suite

Ravel: Piano Concerto in G

Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring

It was all aboard, with emphasis on the ‘all’, for the BBC National Orchestra of Wale’s latest outing in its St David’s Hall residency. Over one hundred musicians filled the platform for the two outer works, slimming to almost chamber size only for the central one, Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G. To the hall’s veteran concert-goers it looked a mite overcrowded, even more so in Prokofiev’s Scythian Suite, which opened the concert. The reason for that was the reflection in the massed ranks of the frequent congestion in the score. Ancient nomads, the Scythians lived beside the Black Sea. They were tubby despots, lived on a diet of fish and mare’s milk, and were less than charming. Their legends included familial deities based on a sun god. Urged by Diaghilev, Prokofiev wanted to create a mimodrama from the story of how a hero rescues the sun god’s daughter from the unwanted attentions of her father, but the project ended up as an orchestral suite, almost in the same way that Stravinsky’s The Rite Of Spring, another of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes projects, has now lost its provenance as a staged ballet. In both works, those origins, apart from the notoriety surrounding the Stravinsky premiere in 1917 and its significance as a landmark of contemporary music, can with no great loss be left on file as historical happenings.

These links – the jazz-inflected concerto perhaps reminding us of Stravinsky’s interest in that music and of jazz’s reputation for wildness – allowed conductor and orchestra to perform with a lack of restraint that appeared as though it might have been pre-ordered. Distressed damsels and their rescuers, even on an heroic scale, deserve some king of ethereal treatment in music, and Prokofiev finds time in the suite for a few choice instruments and combinations to float out of the throng. But the throng’s mostly the thing, the music’s invocations, incantations and general firepower unleashed in full knowledge that this is such a dense score that someone could play Land of Hope and Glory in the middle of it and not be heard, let alone affect the outcome. Not for the first time (and this an iteration of what some conductors have said) did the hall’s finely-balanced acoustics threaten to be overwhelmed. But as an introduction to the deferred Rite, the reverberations hung around in the mind.

Søndergård clearly intended barring no holds on the night, an approach to Stravinsky’s iconic work only justified by faith in the musicians’ instinct to cling on when the going gets manic. The composer’s palette is multicoloured and visionary, his rhythmic framework stutteringly violent, his outbursts – those horns in the ‘Ritual Of The Ancients’, for example – contrasted with discrete, almost folk-like, tunes. It still adds up to a musical tall order, but if this is a work to listen to with heads below the parapet, as it were, Søndergård’s impassioned reading was the one to go for. The orchestra had its measure, from the opening bassoon in high register to the slashing string chords with brass accents that begin ‘The Auguries of Spring’ and the drum-bashing that precedes ‘Glorification Of The Chosen Victim’. Still, subtlety is possible: this is ceremonial music, in many ways orderly and processional, and the wild-eyed baa-baas depicted in this performance sometimes seemed over-anxious to get to the blood-letting bit. Søndergård would surely excuse that, assuming no-one had fluffed a line, by saying the music symbolises a surge of creativity, a creative spring, and you can’t hang back with that. Nor did he.

The concerto, especially in the sophisticated and unhurried manner essayed by soloist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, was in retrospect light relief. The orchestra possibly underplayed its eccentricities (woodwind shrieks, brass glissandi) and the soloist certainly never played up to them. The jazz elements notwithstanding, Ravel’s concerto is Mozartian, but only insofar as Mozart was ever in diverting mood when it came to piano with orchestra. Its central movement, a bluesy adagio assai, is not so much profound as bitter-sweet, and Bavouzet made light of its deceptive simplicities, especially those associated with the slow spinning of single notes and their stately progress. Percussive passages, too, were given full expressive weight, leading to that wonderful line-abreast finish. The final movement was reprised. In all three works, the finishing-line was an event with an almost palpable momentum, though all we had come through in the concerto compared with the other two works – and it was no worse for that – was a bathe in exquisite surface sound rather than a physical shake-up.

This concert was also given at the Brangwyn Hall, Swansea, on June 9. The Swansea concert was recorded for broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on June 15 as part of BBC Music Day, after which it can be heard on the BBC website for thirty days. The Cardiff concert was recorded by BBC Radio 3 for future broadcast on ‘Afternoon On 3’.

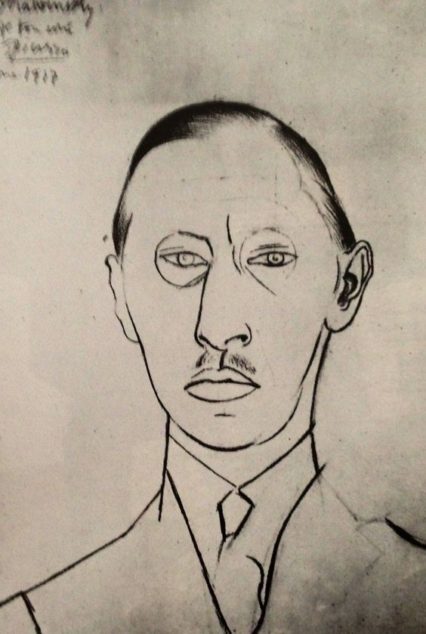

Header photo: Stravinsky in 1910

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.