Steph Power is at the BBC Hoddinott Hall in Cardiff for the second the second in a three-part mini series exploring ‘Tales of Travel’, composed by Paul Hindemith with the National Orchestra of Wales.

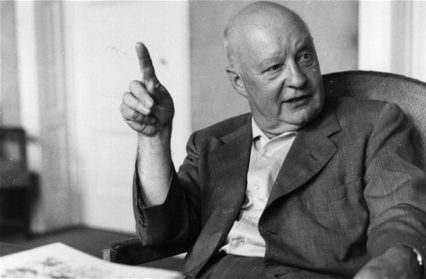

Paul Hindemith is a composer who, despite a plethora of available recordings, pops up far less often on concert programmes than he deserves. In a culture obsessed by anniversaries, 2013 was notable for its copious celebrations of Wagner and Verdi (birth bi-centenaries), and Britten (centenary). But in the fiftieth year since his death in 1963, aged 78, Hindemith appeared to merit just a cursory glance, as if he were a mere blip on the radar of history.

Things were not always so. Indeed, up to the mid-1950s, in the words of Ian Kemp, Hindemith was still being “confidently linked with Bartók, Schoenberg and Stravinsky as one of the four musical giants of the 20th century.” Certainly he was one of the most prolific and versatile of composers, as well as being a viola virtuoso and an influential teacher and theorist. Ironically perhaps, given the falling off in frequency of his works’ performances, he was best known by then for Gebrauchsmusik, or ‘music for use’; a term describing music written for everyday situations, to be taken out and readily enjoyed rather than venerated on the concert platform. But this hardly excuses the neglect of his wider oeuvre, especially the superb 1938 opera, Mathis de Maler.

So it was good to see the inclusion of Hindemith’s 1947 Clarinet Concerto in this tautly energetic afternoon concert from the BBC National Orchestra of Wales; the second in a three-part mini series exploring ‘Tales of Travel’, and conducted here with panache by Alexandre Bloch. In this instalment, sandwiching Hindemith between two diametrically opposed, heavyweight Russian emigrés, the issue was not so much ‘travel’, however, as the far darker ‘exile’.

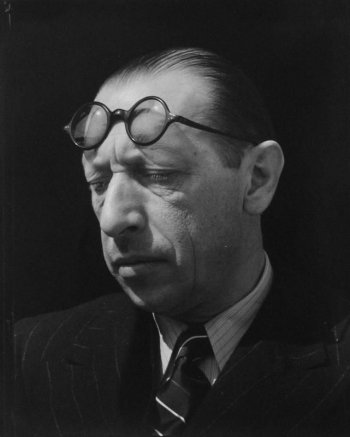

Not that you would have guessed that from the opening piece, Stravinsky’s delightfully colourful but emotionally bloodless Danses concertantes (1942); nor the fact that it was written mid-World War II, shortly after Stravinsky’s eventual arrival in Los Angeles, having suffered a second displacement from Paris. And you would surely never detect that his wife, mother and eldest daughter had recently died within two years of each other (1938-9). Still, the too-easy labelling of this period of Stravinsky as a kind of frigid neoclassicism does no justice to the life-affirming – indeed balletic – vitality of the concertantes, with its snappy asymmetric rhythms and nonchalant air. Bloch and the orchestra captured the work’s sense of an ambiguous brave new world with a winning combination of urbane charm and piquant satire.

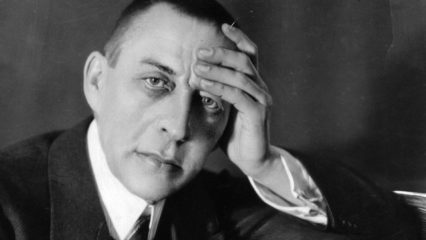

In complete contrast to Stravinsky, Rachmaninoff has been oft-vilified for wearing his musical heart on his sleeve. Composers, it seems, can’t win – but then Stravinsky himself famously described his lanky, somewhat neurotic countryman as a “six-and-a-half-foot scowl”. In truth, Rachmaninoff suffered acutely in exile following the coming of the Bolsheviks in 1917 (talking of anniversaries, 100 years ago), and he never lost the yearning for his Russian homeland.

After settling in the USA in 1918, he found fame as a concert pianist. But while Rachmaninoff and his music were embraced by the public, he found it very difficult to compose. His Symphony No. 3, written in 1936, is suffused with a deeply Russian pathos; specifically in the chant-like theme which underpins each of its three movements, but more generally in its sweeping major-minor nostalgia, almost brusquely interrupted by staunch, rhythmic material and peppered with intensely felt climaxes.

BBC National Orchestra of Wales performed the piece with drive and commitment; Bloch making particular sense of the second movement, with its apparently contradictory blend of rich adagio and brightly effusive allegro. There was some outstanding playing here – Leader, Leslie Hatfield in heart-stopping violin solo, for instance – and some very involving chamber moments: flute-harp-viola balancing clarinet-harp-trumpet amongst other instrumental combinations. Indeed, Rachmaninoff’s handling of the orchestra is wonderfully adept by this stage in his career. And is that a hint of Mahler, even, in the third, bittersweet movement?

Gilmore Music Library, Yale University

There is no such allusion in Hindemith’s Clarinet Concerto which – given that it was written for the jazz clarinettist supremo Benny Goodman – is surprisingly understated. There are no big gestures either; jazzy, ‘American’, instrumental or otherwise. Hindemith had emigrated to the USA in 1940 from Switzerland (like Rachmaninoff), where he and his Jewish wife found themselves fleeing the Nazis; while some in Germany had applauded Hindemith’s apparent stylistic volte face from an astringent modernism ‘back’ to a kind of extended diatonicism, Joseph Goebbels branded him an “atonal noisemaker”.

Nonetheless, not unlike Stravinsky at this time (but with rather less self-consciousness), Hindemith’s music eschews emotional outpouring for a lyrical serenity couched in careful articulation of symmetrical forms – sonata, variation, rondo – shot through with quixotic colour. Prosaically, the four respective movements of the concerto are marked: Rather fast; Ostinato – Fast; Calm and Cheerful (translated from German). So if Bloch’s conducting was less animated here than elsewhere in the concert, it was in keeping with the score. He was no less in command of his orchestra, however, and proved sensitive to the clarinet soloist, Annelien Van Wauwe, allowing her space to eventually flourish in the work’s most outgoing, fourth movement.

Sure and smooth of tone, it’s a pity that Van Wauwe (currently a BBC New Generation Artist) chose not to allow the Hindemith to echo in the audience’s ears, but bounced quickly back onto the platform to deliver an encore from another piece written for Benny Goodman: the last movement of Malcolm Arnold’s more extrovert, obviously jazzier Clarinet Concerto No. 2 (1974). Yes, she and the orchestra played it with gusto. But how typical, somehow – and sad – that Hindemith should effectively be ousted by showy glamour in the process.

Tales of Travel 2

BBC Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff, 28 April 2017

Stravinsky – Danses concertantes

Hindemith – Clarinet Concerto

Rachmaninoff – Symphony No. 3 in A Minor

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Annelien Van Wauwe – clarinet

Alexandre Bloch – conductor

Concert available to listen on iPlayer at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08n238r

This event links with R17, a Wales-wide initiative commemorating the 1917 Russian Revolution

The third and final concert in BBC National Orchestra of Wales’ ‘Tales of Travel’ series is at BBC Hoddinott Hall on Friday 23 June at 2pm

Header photo: Paul Hindemith

Steph Power is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.