Gary Raymond was at the Szene:Wales theatre & performing arts festival in Dresden, Germany, to ask: What can a festival that spotlights the theatre of one nation say about a country?

Programming a festival that spotlights the work of a nation is about as tricky a task as can be charged to an artistic director. For every tradition there is an iconoclast, for every root there is a branch. For the Societaetstheater in Dresden, which this week has been welcoming a programme of the performing arts of Wales, it has been an unexpectedly smooth run of eclecticism. Brit Magdon and Andreas Natterman (with the support of British Council Wales and Arts Council Wales) have pulled it off.

Each performance so far has been singular, hearty, bombastic, tilling a field normally unfamiliar to the mainstream; but, it has to be said, taken together the shows on at Szene:Wales have spoken of some familiar representations of what it is to live in Wales. It would be a brave soul indeed who predicted bringing these shows together would work as well as they have done, but the German audiences have embraced the bombast, and have seen work that is without doubt worthy of this international stage.

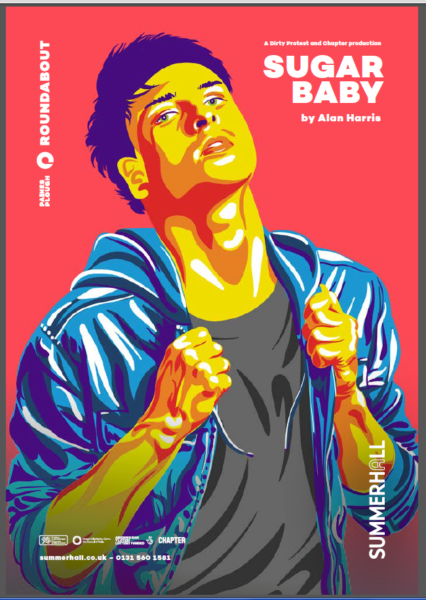

As I wrote earlier in the week, Jo Fong’s An Invitation… held up as a perfect opening salvo – intelligent, daring, and fun. It took a short while for the audience to give themselves up to it, but give in they did. Perhaps just as energetic, but apart from that quite a different encounter, was Dirty Protest’s Sugar Baby. This is a production that perhaps has more life in it than most would have thought when it debuted a couple of years ago. Alex Griffin-Griffiths, you feel, has grown with the part. A lovable rogue, yes, and that glint in his eye as Marc bounds around Cardiff pinballing from one unsavoury character to the next may get you so far with a British audience used to forgiving wretchedness when it has a certain swagger, but would it be enough for Dresden? Alan Harris’ superb monologue is appropriately smattered with profanity, and Catherine Paskell’s flexing direction does everything it can to knacker out her actor, but what charms are required in the refined halls of Dresden’s oldest theatre? Authenticity counts for a great deal in the end, and the moments when you feel the evening might be lost – when Griffin-Griffiths’ performance gets pretty close to the bone, or when Harris’ story makes that glorious leap into magic realism – the audience once again go along.

There are a few gasps, a few heads in hands during Sugar Baby (it’s performed in the round, and so is perfect for audience-watching), but they are in it, not pushing away. Harris’ script is geographically pretty site-specific, but it doesn’t matter, for this is literature, and it is about world building. As a writer, you either pull it off or you’re nowhere. I was lucky enough to be the only critic to see Harris’ play for the National Theatre Wales when they collaborated with National Theatre, Tokyo in 2013 and The Opportunity of Efficiency was an ambitious project that no writer would turn down. Harris did a good job with it, but it is here, in Fairwater and Canton, where he really flies. It would be a curt audience indeed who turned their backs on this strange ugly beautiful modern fairy tale.

And it is fairy tales that perhaps the most discerning German would have been expecting from a “Welsh festival”. On the third night, Adverse Camber, a Derbyshire company, bring Michael Harvey’s telling of the Mabinogion, Dreaming the Night Field, to Dresden. This is the tradition, after two nights of stomping and sweating. But the best storytellers serve to remind us that these ancient myths are not for the coy, and Harvey is a master near the top of his game. If his prose lacks a certain poetry, it is only the poetry of cliché. Harvey tells the stories in the way they should be told, as if the pub fire crackles and the winds howl outside across the cobbles.

No hifalutin here; these are the stories of kings and magicians saved and maintained for the people. On Newsnight last week, Marvel writer Jim Starlin talked of how the Avengers movies were creating a new mythology for our age. Avengers Infinity War is apparently the second most expensive movie ever made. I’m not saying transporting a pedal harp from Wales to Germany is cheap, but I think Adverse Camber understand the strength of a story is in the telling, not the hype. Michael Harvey has an impressive stage presence, that rare mixture of ego and modesty, both sides deployed expertly and with sincerity. He revels in the stories, they are sermons, an he treats them as if they have grown richer with age, not simply become classical. They are not updated, reimagined or “reduxed”, but they are unmistakably presented with a modern swagger. There are no computer graphics on offer, just atmosphere, tall tales, and Harvey’s charisma.

Harvey is given ample support by Stacey Blythe, an instrumentalist and vocalist, and Lynne Denman who lends her ghostly vocal talents to an adventure that seems to waver in and out of a dreamlike focus. The Mabinogion, with its non-Aristotelian bends and edges, is perhaps, more than most ancient cycles, its own type of beautiful relevant absurdity. In its role as a national fantasia The Mabinogion is deathless, but productions such as Dreaming the Night Field can teach us knew things about why it has remained relevant. It is tethered to, and speaks of, the imagination of a people.

And Szene:Wales is about that as much as it’s about such new, skittish terms as “outreach” and “soft power”. The economics of art will come and go – the carriers of the Mabinogi have seen this over centuries. Enablement is rooted in the present, almost the opposite of what great storytelling needs to be. Art has faced greater threats than Brexit, or the right wing public funding holocaust to the gods of greed. Szene:Wales is a small event, but it is making connections. Even if it makes only one person reflect on their place in the universe, it has been worth it. Wales’ position in this is as a platform for the creativity of its people, and it is important to ensure this is never upturned, and the artists of Wales are expected to promote a national narrative. Wales is whatever its artists say it is; it must not be a brand smoothed out in the refineries of Cardiff Bay.

We must remember that Wales is on the corner of a continent that survives whether the body of the European Union has Westminster on its Christmas card list or not. If we can prove we have creativity in our hearts, our relationships will continue. Clementine Schniedermann, the Cardiff-based French photographer, is exhibiting I Called Her Lisa Marie at the theatre with the support of Penarth’s Ffotogallery, her work based around the fandom of Elvis, and it speaks of a certain – and familiar – aspect of Welshness. There is a tacit connection in these images, taken from Memphis to the Welsh Valleys, of a melancholic, somehow wilting, existence.

Matthew Warchus’ acclaimed film Pride is on show here too, and although some quarters have questioned why it is so lacking in Welsh contributors, it still depicts a Welsh story and does it with affection and, arguably, respect. This is how a nation takes part in a global conversation. Apparently, we’re calling it “soft power” now. Whatever excites the political classes – all that really matters is that in the halls of the gatekeepers walk people with the vision to make sure festivals like this happen. And then just let the artists do their thing. “Wales” will do fine.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, critic, editor and broadcaster.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.