St David’s Hall, Cardiff, July 24 2015

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra

Angharad Morgan (soprano), David Fortey (tenor)

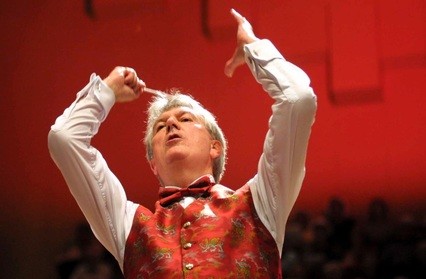

Conductor: Owain Arwel Hughes

Johann Strauss II:

Overture Die Fledermaus

Blue Danube Waltz / Roses From The South / Tritsch Tratsch Polka / Annen Polka / Emperor Waltz / Champagne Polka / Bandit’s Galop / Furioso Polka / Thunder and Lightning Polka / March from The Gipsy Baron

Franz Lehar:

Vilja (The Merry Widow) / You Are My Heart’s Delight (The Land of Smiles) / On My Lips Every Kiss Is Like Wine (Giuditta) / Girls Were Made To Love And Kiss (Paganini) / Love Unspoken (The Merry Widow) / Gold And Silver Waltz

Johann Strauss:

Radetsky March

After receiving an anonymous blood transfusion on his deathbed, Alban Berg raised an eyebrow and said he hoped the experience would not turn him into a composer of operetta. In happier circumstances, his concern would have been more than a joke, because the idea of musical frippery ‘infecting’ the serious side of Viennese musical life, represented by the continuum of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Bruckner, Wolf and Mahler, and the moderns (of whom Berg was one), served to keep them apart. Of Viennese operetta and other light music, it was said that with most of the city’s audiences more in thrall to it than to any other sort of music, it was no wonder their Empire collapsed. A harsh and exaggerated view, no doubt, but indicative of the width of Vienna’s social schisms at the turn of the 20th century.

With operetta’s greater popularity in mind, it was perhaps no surprise that a Welsh Prom titled ‘A Night in Vienna’ should concern itself not with unsmiling, ‘absolute’ music but with Hapsburg froth. Inexplicably, though, only three composers were represented: Johann Strauss, his ‘Waltz King’ son Johann Strauss II and Franz Lehar, Johann Vater making the cut only on account of his Radetsky March. It closed the concert with the now-obligatory hand-clapping, encouraged by arch-traditionalist and Welsh Proms founder Owain Arwel Hughes and the Merseyside band, who stayed in town for the Last Night concert on Saturday. With a little more thought, the effervescence might have been combined with music from some of those ‘serious’ composers who were not as averse as Berg to a little light fantasy. Schoenberg, Webern and Berg himself all made arrangements of Strauss II, the better to show its qualities in the best possible light.

Vienna’s dichotomies are there in the eponymous Paganini’s ‘Girls Were Made To Love And Kiss’, from Lehar’s operetta. The girls are intended to be the recipients of osculatory attention, but the words, in their English translation at least, can be read as ambiguously Freudian. This was the first of Lehar’s Tauberlieder, written for the celebrated tenor Richard Tauber, the opera itself an example of how shallowness of emotion was often inversely proportional to impossible complexity of plot. The eager young voice of David Fortey proved in this and in the most famous Tauberlied, ‘You Are My Heart’s Delight!’, that there’s no way such tunes can lack anything when surgically removed: operetta ditties are the same whether cut loose or embedded. Incidentally, the way German and English are more interchangeable than ever when dealing with operetta is a further reflection of divergence: no-one refers to Die Fledermaus as The Bat, nor is ‘You Are My Heart’s Delight!’ known as Dein ist mein ganzes Herz! in any but German-speaking countries. For the record, Hughes and the orchestra added a couple of items to the programme, including the March from The Gipsy Baron (Der Zigeunerbaron, to you). He relishes this sort of selection, though repeating a quote to the effect that ‘Roses From The South’, a waltz from The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief, possessed Mozartian charm, was the repetition of error. Charm, yes; Mozartian, no. And on linguistic grounds alone, it should be against the law to call the operetta anything other than Das Spitzentuch der Königin.

All these marches, polkas and waltzes would be merely strict tempo affairs were it not for the need to sculpt their picturesque settings, an acknowledgement made by Hughes and the orchestra with generally stylish phrasing and unforced dynamics and, in the faux-symphonic Emperor Waltz, a feeling that the music might have been more than a series of melodic paragraphs smartly put together. Moreover, they never lost sight of the music’s often careless revelry, which in other hands and before a tin-eared audience might be accomplished by routine or sloppy playing. None of that here. The Merseysiders were in good form and clearly enjoying themselves (witness the cork-popping kitchen department in the Champagne Polka), Hughes never failing to count the bubbles or, in the vocal items, to forget that David Fortey and Angharad Morgan, another fresh voice with a confident reach, were being accompanied, and all that meant in terms of allowing the singer to be heard as well as dramatically conjoined. No shrinkage for the soprano in ‘On My Lips Every Kiss Is Like Wine’, the title-role song from Lehar’s ambitious Giuditta, or the ‘Vilja-lied’, Glawari’s nostalgic song from The Merry Widow, sung here with Pontevedrin attractiveness, and with an opera seria exuberance reflective of a character hemmed in by men. ‘Love Unspoken’, the duet for Glawari and Danilo from the same operetta, was sung after Hughes had pronounced Fortey and Morgan man and wife, which they are. Was that a tear forcing itself reluctantly into the critic’s eye? Indeed it was.

Photograph of Owain Arwel Hughes courtesy of St David’s Hall

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.