Adam Somerset reviews Llareggub by Peter Blake, a collection of illustrations in reference to Dylan Thomas’ classic Under Milk Wood.

Copyright Sir Peter Blake

Under Milk Wood in this commemorative year is recipient of a range of treatments. An opera and a ‘live performance adventure’ are in preparation. Terry Hands has returned with intensity to the words themselves. Peter Blake’s homage, Llareggub, as mounted by the National Museum, also has the words in hand-writing and, every afternoon, the rich tones of the radio production in accompaniment to the one hundred and seventy exquisite postcard-sized images.

A newspaper article last month spoke with other re-interpreters of Under Milk Wood. The term ‘making it relevant’ featured more than once. Poor Dylan, he is just so old, so history. Metaphors like his being the original rapper are spun; it is not just the sense of desperation it conveys, it is the giveaway of inattention, to both man and verse. Those elements of the verse that belong utterly to their time tell us that the surface glosses of our 2014 are equally as evanescent. Many of the trades of Under Milk Wood have vanished. The last time I was in Laugharne, a sunny September morning, its streets were empty. A function of the art that lasts is to free its audience from the chains of an enclosing contemporary fixation.

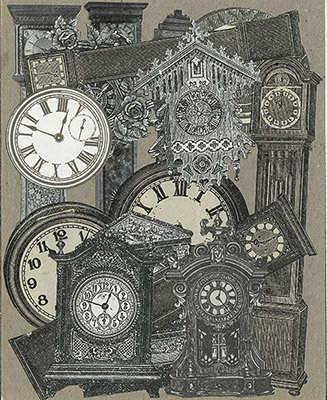

One pleasure of looking into Peter Blake’s imagined Llareggub, contained within a single upper gallery, is to gaze at another older Wales. It is a world of milk churns on the street and boys with side partings and home-knit chunky tank tops. PC Atilla Rees wears the high-domed police helmet. Dai Bread busts a button off his waistcoat on his rush to work. Mog Edwards dresses himself in boater and bow tie. Lily Smalls tucks her dress into her bloomers to scrub the front step.

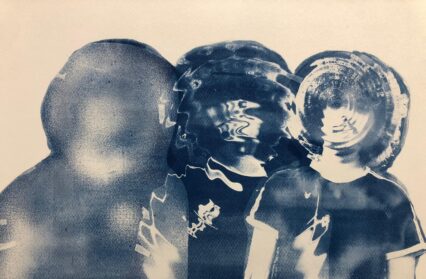

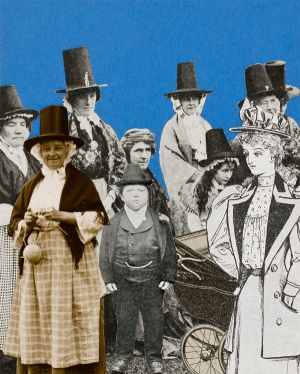

The works in Llareggub divide into three categories, portraits, the dreams close to waking, and the largest, eighty-four illustrations of scenes and locations. Many of these are small and delicately created collages. The playfulness of the pop artist with the wit, irreverence and occasional surrealism and sauciness, is a constant. Fine art here casts a respectability over the odd image of priapic alarm that in other contexts would incur tabloid protest and an eighteen age rating. Humphrey Bogart appears puckishly among the portraits. Mrs Willy Nilly is conceived as an apparent Margaret Attwood. The depiction of Mae Rose Cottage looks as if she might have stepped straight form a sixties David Bailey photo-shoot. In the dream of Organ Morgan the Women’s Welfare become a troupe of high-kicking dancers on a moonlit rooftop.

Copyright Sir Peter Blake

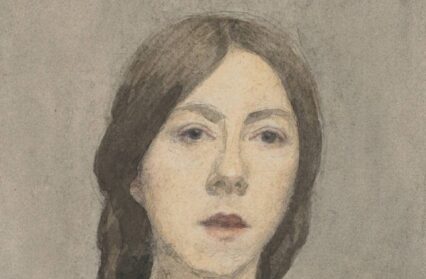

Peter Blake is of that generation trained with rigour in the craft. The quality of draughtsmanship is superlative. Lord Cut-glass, easy to mock, carries here a look of loss and desolation. Mr Pritchard is a West Wales ‘Everyman’, his one skewed eye the only indicator of a less-than-ordinary destiny. Mary Ann Sailors, at age eighty-five years, three months and a day, has a spider’s web of lines and creases across her chin and mouth. The sightless eyes of Captain Cat are a range of haunting pallours.

The gallery lighting is muted, an effect to make the few water colours stand out. The bare branches that are backdrop to baking Welshcakes in the snow are rendered in a millimetre’s thickness. A waterfall has the kind of intricacies of wash and white that Brushes cannot do. The effect is made greater by apposition to the red flames. When Bessie Bighead raises her head to kiss Gomer Owen a tendon in her jaw is drawn taut. Blake renders the hair of both in shades of russets and reds, but does not omit the truth that the puffed up hair of the elderly gent cannot fully hide the print of the skull beneath.

Llareggub is a major exhibition and the National Museum has launched the Dylan Thomas year on a high. It has attracted a large and diverse public audience. Not so the critical community. One London broadsheet launched a disapproving review without the critic troubling himself to have actual sight of the exhibition. The Welsh cultural journals have collectively stayed away. The commissioning of seven pages of laborious cut-and-paste promotion of a United Nations agency is deemed a loftier cultural service to Wales than responding to the efforts of real world curators and exhibitors.

Copyright Sir Peter Blake

You might also like…

Continuing our series of interviews with significant figures in the world of Dylan Thomas, Jasper Rees talks to John Goodby, poet, critic and Professor of English at Swansea University. Goodby’s book The Poetry of Dylan Thomas: Under the Spelling Wall (Liverpool University Press) was published in 2013. His new edition of The Collected Poems of Dylan Thomas (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) is published in the month of the centenary of Thomas’s birth.

This piece is part of Wales Arts Review’s collection, Dylan Thomas from the Archive.

Adam Somerset is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.