The Nightingale Silenced, transcribed by her nephew Jim Pratt from three previously unpublished manuscripts, offers a unique account of the last years of the life of Margiad Evans, which was irreversibly changed by the onset of epilepsy at the age of 41.

The first part, Journal in Ireland (1949) tells of a joyous and inspirational holiday, free from epilepsy. The second, Letters to Bryher (1949-1958) is a selection from letters to Evans’ friend and benefactor Winifred Ellerman (the English author Bryher). They contain a vivid account of her pregnancy, the birth of her daughter, her frustration at the impact of her illness on her writing, and finally resignation at the terminal nature of her condition. The third part, The Nightingale Silenced (1954), is an evocative and harrowing memoir describing her experiences as an inpatient after her condition became acute. The book closes with five of her poems, written during her final months in hospital, which she intended to publish with The Nightingale Silenced. She died at only 49, in 1958.

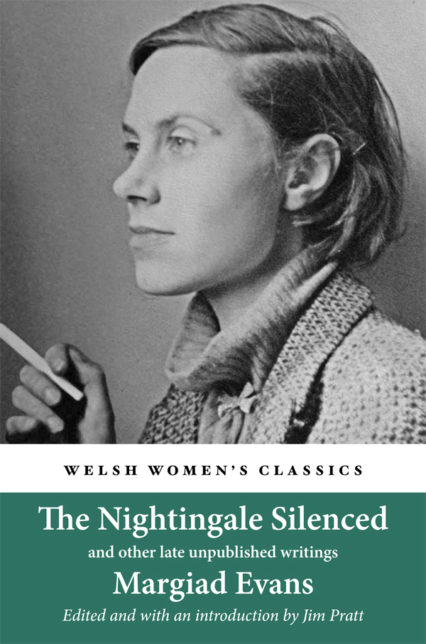

This new compilation from a courageous young novelist and poet of great promise, silenced too soon, is an enlightening example of writing on the experience of terminal illness. The Nightingale Silenced is the twenty-ninth publication in the Welsh Women’s Classics series, an imprint that brings out-of-print books in English by women writers from Wales to a new generation of readers. An extract from the introduction to The Nightingale Silenced and other late unpublished writings.

The novelist and poet Margiad Evans (my aunt Peggy Williams, née Whistler, 1909-1958) has been classed as one of the finest English-language prose writers of the twentieth century. She published four novels, two poetry collections, two volumes of autobiographical prose and a short story collection, but the bulk of her writing in letters, journals, notes and plays remains unpublished. Honno Welsh Women’s Press have brought together two of her later unpublished works linked by a series of letters to a friend and confidant that shed light on the later piece. These writings span a critical period towards the end of her life, cut short by what turned out to be a terminal brain tumour. Cruelly, this manifested itself for several years in increasingly severe epilepsy. Her struggle to come to terms with this most debilitating of illnesses, to write her way around it but not to submit to it, is a constant theme in both the letters and the autobiographical The Nightingale Silenced. In the end her epilepsy subsumed her, but the period from May 1950 (her first fit) to February 1956 (diagnosis of her inoperable brain tumour) was also a time of hope, and of new friendships curiously enriched by, and resulting from, her illness. It was also a period of intense self-examination, of increasing responsibility for other people (notably her daughter), of frustration at her lack of inspiration and inability to sell her work, and of physical pain and exhaustion in one whom she describes as being ‘very strong. Like a steel rope’. But even when epilepsy had her in its full grip, she remained capable of writing narrative that is harrowing and arresting to read.

The novelist and poet Margiad Evans (my aunt Peggy Williams, née Whistler, 1909-1958) has been classed as one of the finest English-language prose writers of the twentieth century. She published four novels, two poetry collections, two volumes of autobiographical prose and a short story collection, but the bulk of her writing in letters, journals, notes and plays remains unpublished. Honno Welsh Women’s Press have brought together two of her later unpublished works linked by a series of letters to a friend and confidant that shed light on the later piece. These writings span a critical period towards the end of her life, cut short by what turned out to be a terminal brain tumour. Cruelly, this manifested itself for several years in increasingly severe epilepsy. Her struggle to come to terms with this most debilitating of illnesses, to write her way around it but not to submit to it, is a constant theme in both the letters and the autobiographical The Nightingale Silenced. In the end her epilepsy subsumed her, but the period from May 1950 (her first fit) to February 1956 (diagnosis of her inoperable brain tumour) was also a time of hope, and of new friendships curiously enriched by, and resulting from, her illness. It was also a period of intense self-examination, of increasing responsibility for other people (notably her daughter), of frustration at her lack of inspiration and inability to sell her work, and of physical pain and exhaustion in one whom she describes as being ‘very strong. Like a steel rope’. But even when epilepsy had her in its full grip, she remained capable of writing narrative that is harrowing and arresting to read.

To her, what mattered was what she could see or hear or feel. Margiad had been mesmerized by nature since, as an eleven-year-old, she spent a year with her younger sister Nancy (otherwise known as Sian) largely unsupervised on a farm by the banks of the River Wye. Such was her subsequent devotion to the natural world which inspired her that she elected, from 1940-1947, to live in isolated cottages in the Welsh borders some distance from the nearest village, Llangarron. In her cottage, Potacre, she attempted to describe and rationalize her place in nature, summarizing her perceptions in one striking paragraph in Autobiography:

All, all in sight and hearing was Nature pouring itself from one thing into another, spending and creating, running like the wind over the body of life, and flowing like blood through its heart. All changed, and nothing changed. If I may keep this knowledge, this perpetual life in me, anybody may have my visible life; anybody may have my work, my smile, if I may go on sensing the thread that ties me to the sun, to the roots of trees and the springs of joys, the one and separate strand to each star of each great constellation.

But her quest for understanding her place in the scheme of things was fated to be complicated and indeed compromised by the events that overtook her in 1950 when, without warning, epilepsy struck. From then on, she wrote through the twin prisms of her epilepsy and her belief in the power of the natural world.

To write and publish about one’s own epilepsy was remarkably brave, given the suspicion and social stigma attached to the illness. In 1960 her contemporary and later friend, the American neurologist William Lennox, called for change, protesting that ‘epilepsy is an illness that should not call for secrecy any more than diabetes […] Yet many epileptics live in a cocoon of concealment. Breaking this skein will give them […] a new freedom. Epileptics can perform this miracle […] for themselves.’ This Margiad did in her writing, exposing her doubts, anxieties and fears openly, often at times of great pain and discomfort, exposing her own condition to public scrutiny. For her, to write of what was on her mind was a necessity. ‘As a pleasure, writing has great limitations: as an outlet, none’, she remarked in The Nightingale Silenced.That, and its predecessor A Ray of Darkness are amongst the earliest accounts of epilepsy by a patient and as such merit careful analysis by neurologists. As Sue Asbee points out, ‘A major illness forces the need to renegotiate our relationship with our bodies and with the world. Things that we took for granted when we were well are inconceivably impossible once we are not’, and Margiad realised this early on.

Amongst the pain and the anxiety brought on by Margiad’s condition, beauty was something she desperately needed. Throughout her career as a writer she sought to give permanence to its fleeting visitations, and through this publication of her later manuscripts that final ‘absolute symbol’ of the ‘nightingale silenced’ is at last made available to her readers.

Novelist, essayist, poet and writer of short stories, with a lifelong identification with the Welsh border country, Margiad Evans – the pseudonym of Peggy Eileen Whistler (1909-1958) – was one of the most remarkable women writers of the mid-twentieth century. She published four novels and was known for her brilliant descriptions of the natural world.

Born in London, Jim Pratt MBE was evacuated during WWII to Monmouth, close to the Llangarron home of his aunt Peggy (Margiad Evans.) He has transcribed several of Margiad Evans’ manuscripts, published essays on her, as well as giving talks on her work and life. He lives near Edinburgh.

Margiad Evans bibliography

Novels: Country Dance, 1932; The Wooden Doctor, 1933; Turf or Stone, 1934 and Creed,

1936). A Country Dance was republished in the Library of Wales. The Wooden Doctor and Creed have been republished by Honno in the Welsh Women’s Classics series

Poems: Poems from Obscurity, 1947 and A Candle Ahead, 1956

Autobiography, 1943 and A Ray of Darkness, 1952),

Short Stories: The Old and the Young, 1948