In this personal essay, Ioan Marc Jones explores the history of slate mining in Blaenau Ffestiniog through the stories of his childhood and examines the ways in which slate has come to inform his notions of Welsh national identity.

Five blokes were smoking cigarettes at the bottom of the quarry. I expected my dad, lungs black as slate, to join them. As my brothers and I ascended the mudstone mountain, however, my dad charged in front. Slabs cracked under his mammoth steps and shingles splintered in his wake. Fifty yards ahead of my brothers and I, my dad turned to mock our performance: Bechod, ey boys.

My dad climbed the same quarry when he was a child. He reached the top, he said. My brothers and I didn’t make it that far. We were metropolitan kids, timid and tepid, weakened by the flatlands and manufactured parks of London. Our idea of a good time was playing football on well-groomed fields and climbing pitiful oaks. My dad was North Walian, sturdy and stubborn, strengthened by the jagged terrain. When my dad was a kid, he was leaping from rocks into the tempestuous Irish Sea and scree running down Cadair Idris.

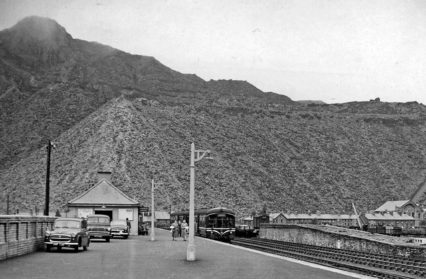

My brothers and I fashioned seats amid the shingle half way up the quarry. My dad wandered down to join us. The four of us could see the entirety of Blaenau Ffestiniog. Rows of small grey houses formed an imperfect circle between the peaks of Snowdonia and the towering quarries. The railways shaped the landscape and little shops added necessary bursts of colour. My dad pointed towards his childhood home. It was small and grey.

That vast pile of sedimentary rock provides an appropriate vantage point. Slate defines the local and national identity of folks from Blaenau Ffestiniog. It indeed defines my dad’s national identity. And since our trip to Llechwedd Quarry, the history of Blaenau’s slate industry has become essential to my own understanding of nationhood.

The North Walian slate industry began in earnest in the mid-eighteenth century. The Ordovician veins, which run through Betws-y-coed all the way to Porthmadog, provide the richest and most refined slate around Blaenau Ffestiniog. The ruling classes invested heavily in Ordovician slate. Folks from across North Wales and beyond emigrated to Blaenau to find work. Blaenau was born from this emigration. Blaenau, indeed, was born from the attraction of slate.

By the early nineteenth century, the slate mining industry had enticing prospects and firm foundations. According to John Davies in Hanes Cymru, slate was beguiling to investors – more beguiling, in fact, than the coal industry. We could still see the results of this investment from midway up the quarry: rusting cableways, decrepit shantys and worn-out mills. But it was investment in steam that brought the greatest long-term benefits to Blaenau. Railways built across North Wales – primarily owned by Ffestiniog Railways Company, the oldest surviving railway company in the world – hastened the rapid increase in slate production and continues to attract tourists today.

The railways served a stranger purpose, too. When my Nain and Taid were young, their friends would take coughing children on the commercial trains, stick the child’s head out of the window and subject them to the mountain sulphur. This, apparently, would cure their cough. When my dad took me on Ffestiniog railways, sixty years later, I stuck my head out of the window purely for enjoyment. The coastal wind gave me a sore throat. To cure the illness, my Nain suggested that I should ride the railways through the sulphur mountain and once again stick my head out of the window. I rejected her advice, as it seemed counter-intuitive. I also rejected my Taid’s advice of wrapping a sweaty sock around my throat, as it seemed archaic.

With the help of the railways, the slate industry was booming by the second half of the nineteenth century. Production of slate in North Wales, Davies explains, increased from 45,000 tons in 1851 to 150,000 tons in 1881. During these booming years, Blaenau’s population rose from 3,460 to 11,274. This growth hastened ribbon development, which provided workers with small grey houses alongside Blaenau’s ragged roads. The locals built the first churches – which later became hubs of non-conformism – and the first schools – which later became the hub of my dad’s nascent non-conformism. By the end of the nineteenth century, Blaenau was a fully functioning town – still reliant, for the most part, on slate.

In the early twentieth century, the rise of North Walian slate gave way to a rapid decline. Folks conveniently blame the World Wars for the loss of industry. This interpretation is too simplistic. As Alun John Richards explains in Slate Quarrying in Wales – a cherished book my dad gave me following our trip to Llechwedd – the decline of Welsh slate started long before the conflict.

Despite an artificial boom from 1901 to 1904, slate was becoming increasingly unfashionable. Consumers continued to use slate for roofing, but used other materials to cover their floors. Wealthier folks buried loved ones beneath grandiose mounds of alien stone – not slate, as was once their wont. Manufacturers used concrete, not slate, for windowsills, doorsteps and lintels. Slate still often formed the bodies of billiards tables, but it was increasingly of the cheaper Italian variety – not the refined, and thus more expensive, Ordovician slate.

The World Wars, while not entirely to blame, certainly hastened the decline of slate. According to the grim rhetoric of wartime, the slate industry was non-essential. The essential industries therefore expropriated indispensable parts of the slate industry. Machinery once used to harvest slate was melted down to support the armaments industry. Appropriate quarries were transformed into factories and quarry steamers were converted into battle ships. Many working class men emigrated to work in the essential industries, leaving slate behind, while others became soldiers. Some miners never made it back to North Wales. Some died in the trenches of Gallipoli, the banks of the Somme and the fields of Flanders. Those fortunate enough to return were often left jobless.

The decline of slate ruptured Blaenau’s local economy. Rather than rest on their laurels, however, the people of Blaenau invented novel ways to use the excess mountain of slate. Local authorities and businesses, my dad told me, wrote instructions on slate signs. Landlords furnished pubs with slate tables and slate chairs. Folks settled pints on slate coasters and stubbed cigarettes in slate ashtrays. A few miles down the road from Blaenau, workingmen used slate to rebuild the National Slate Museum, which today verily makes it difficult to differentiate relic from wall.

Some of the quarries have reopened in recent decades, but former prosperity is unachievable. Tourism has overtaken slate as the primary source of revenue for Blaenau Ffestiniog. The sentimental commodification of slate soon followed the increase in tourism. Slate coasters, once so essential to the drinking classes in the valleys, are now ready for purchase at exorbitant prices. Slate picture frames cost around ten pounds and make for a rather lousy Father’s Day present. All the classic memorabilia is available in slate form: necklaces, keyrings, even shot glasses. When I was young, my dad bought slate tablemats, which we still use when my Nain comes to London. It reminds my Nain that she has a home away from home and I suppose it serves a similar purpose for us, too.

The industry has indeed declined in Blaenau Ffestiniog, but slate continues to define the town. And ever since that day running around the quarries with my surprisingly agile dad, I’ve been fascinated by slate. I perpetually ponder this fascination. Why does this ostensibly obsolete entity continue to define my dad’s hometown? Why has the history of the North Walian slate industry imbued in me a sense of belonging, a sense of national identity?

As a young boy growing up in London, I struggled to identify as a Welshman. This was despite my dad’s best efforts. Like so many Welshman who moved to England, my dad used rugby to affect national pride. Pictures of famous Welsh players – Gareth Edwards, Jonathan Davies, Barry John – graced the walls of our home and a surfeit of hand-fashioned Groggs occupied our mantelpiece. When I was five, my dad bought my brothers and I Welsh kits and took us to Twickenham when Welsh teams were in town.

I remember one occasion vividly. It was silent in Twickenham but for a horn. Suddenly twenty thousand Welshmen erupted to sing the national anthem and not one of them missed a word. My dad was the loudest. His orotund voice boomed with utter abandon. His eyes were shut, his hands were sprawled across his chest.

My brothers and I attempted to join in. We used a tactic my mum taught us and started to sing an English version of the anthem: ‘my hen laid a haddock’ replacing ‘Mae Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau’. We felt like passionless Londoners mimicking, perhaps even mocking, the Welsh. That feeling essentially defined my youthful national identity.

My dad convinced my brothers and I to play rugby, too. We joined London Welsh. I was a winger until I spurted a little and switched to number eight. My dad would watch me play and praise my speed. He said I could play for Wales. I was okay, I suppose. But there was a problem: I preferred football – an English sport, according to my dad.

I quit playing rugby when I was thirteen. I blamed the London state school system for their lack of rugby training, insisting that my privately educated friends enjoyed a huge advantage. My dad was disappointed. He watched me play football a few times, but, despite my evident ability, far superior to that of rugby, he offered little praise. I couldn’t play football for Wales, apparently.

I always felt it was rather trivial to accept national identity solely on sporting grounds. I understood why rugby and football fans forged an imagined community based on an inflated piece of leather. They sought comradery. I have indeed often overstated personal allegiances to sporting teams for similar ends. It’s the same reason ostensibly apolitical folks join political parties and amoral folks volunteer for charity. It’s endearing, actually. Who doesn’t deserve comrades? But national identity, I thought, had to mean something grander, something more profound than three feathers on a shirt.

Slate succeeded where rugby failed. The history fascinated me, of course, but the symbolism of slate proved truly beguiling. It offered a sense of national identity not because the industry was based in Wales, but because it was so quintessentially Welsh. Like my dad, and indeed my Nain and Taid, slate was sturdy and strong, solid and stubborn. And like my understanding of the Welsh national identity, the slate industry was romantic and embedded in history.

The belligerent Welsh poet R. S. Thomas encapsulates this national idea best: ‘There is no present in Wales/ And no future/ Only the past.’ The slate town of Blaenau Ffestiniog is a concentrated microcosm of this national idea. In my experience, folks in Blaenau seldom speak in the present or future tense. My North Walian kin perpetually recite stories from their childhood and the childhood of their parents. Notions of political ‘progress’ are understandably met with scepticism, as ‘progress’ has often undermined the communities of North Wales. And slate, an essentially obsolete entity in terms of exchange and utility value, continues to define the town.

I recently told my Nain that I was writing about Blaenau Ffestiniog. She responded with plenty of stories about the slate industry. One modest portrayal of My Nain’s childhood in particular spoke to my feelings of Welsh national identity. It was based in the past, beautifully simple and effortlessly romantic. In the late twenties, my Nain would go with her friends every day after school to watch worn-out miners descend the slate mountains. At precisely four o’ clock, my Nain claims, the flourishing quarries, once packed with hundreds of hardened workers and booming machinery, came to a sudden halt. Within twenty minutes, my Nain and her friends would witness hundreds of miners – the unsung heroes of Blaenau Ffestiniog – disappear on stagecoaches. My Nain would then say goodbye to her friends and stroll back to her small grey house.