What stays with me is the gravestone. Set in the grass near the front door of the church looking over Porthmadog, it has the modesty of a postage-stamp and yet the insistence and belonging of a much larger structure. It sits there with only his name and dates on it. Persistent, present, it is on its own. And perhaps when the grass is mown and the cuttings cover it, it will disappear from view. It says something about the man; and perhaps it says everything about the man. Attached to the Anglican Church, near it but not quite of it. He was not of anything; he was an in-between. What seemed was so often not the case. One thing was sure: he loved the Church. Not its functions, not its paraphernalia, but its presence; the quiet of empty churches was his metier. The long arm of history was his chosen territory; the silence, the quiet persistent reverberations of time.

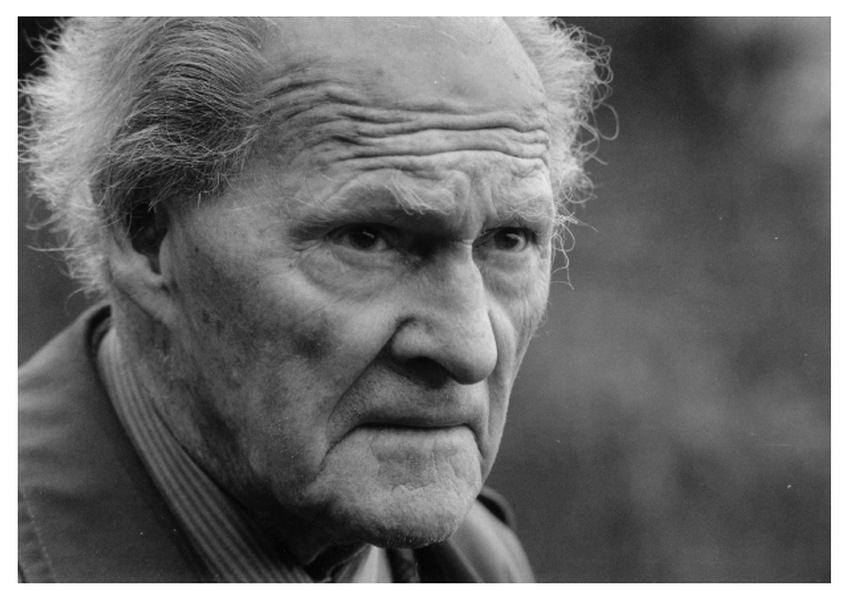

‘I don’t much like weddings. Too much display and nonsense. But I like funerals; quiet, firm, not too long; and final.’ So he told me over breakfast at a conference in the teachers training college in Barry. The previous evening we had gathered at the bar, chatting, friendly, no axe to grind, and R.S. was close to the bar, a half of beer in a handle glass in his right hand. His body was tall, and he always seemed slightly bent, as if leaning to catch something, a nuance, a passing bird, a nudge towards escape. Shortly afterwards he gave a reading. His voice was strong and clear. He read a Wyatt poem with quiet respectfulness, bringing out the musical consonants and the tone of wonder in love – ‘They flee fro me that sometime did me seek/With naked foot, stalking in my chamber…’. He recited a limited number of his own verse, as if acknowledging that other poets were much better than he was. There was no flash about him; none of the awful ‘I am a poet’ posture.

At the dinners in Portmeirion he was reticent. It was as if the larger number of people around him, the more withdrawn he became.Chatting in Welsh to fellow writers, however, he was attentive and interested. When given the choice, he used Welsh more than English. In a later year, at his home in Pentrefelin, he took us around the garden and let us see the wonderful portrait of him by Kyffin Williams, all fine line, rhythm and beauty. He had been given an American literary prize and had spent part of it on a magnificent antique Welsh oak cwpwrdd, its patina deep and austere. He talked of the most out-of-the-way places in Anglesey and Lleyn as if he knew every lane, every corner. It was clear that he was a country man: he had the mind of a farmer or gardener. And yet he had his intellectual distance; he was not afraid of making judgements. As we left he was telling the story of an Englishman in his church, his eyes shining with humour.

I did not attend his funeral. I could not bring myself to elegise; part of the admiring literati. For me, he was still the man in his house, Twll y Cae, his Pentrefelin home, having been to his doctor for a ‘flu jab, handing out biscuits, coming in to the room in his sports jacket and red woollen tie; a host and a very courteous man.

My wife and I called there recently. The front door was open. We knocked and a voice called us in. ‘Left the door open for the delivery man,’ his widow explained. She was watching horse racing on TV. ‘R.S. loved horse racing,’ she said. ‘He followed the horses; he could name them…’She smoked and joked and we could see why R.S. found her very good company.

Like his full name, he was English/Welsh. He could have lived happily in Dorset or Hampshire.The Welsh border-land fitted him, with its wooden-tower churches in villages of little action; their English burr of an accent and rural ease. ‘Remote’ was his word. But he held on to the stream of history. He loved the settled and the traditional. Every time I met him, he wore a tie.