Nigel Jarrett says his latest book, Notes From the Superhorse Stable, is an attempt to do something different with the novel, the most popular form in literature.

No writer wants to be called clever, but a possibly smart way of recognising the hoary criticisms of a novel’s structure is to get your narrator – if it’s in the first person – to pre-empt them.

That wasn’t a deliberate ploy when I started to write Notes From the Superhorse Stable, my latest work of long fiction about an actor who, while ‘resting’, has a job in a Forest of Dean care home. That my protagonist, Francis Taylor, may have seen his acting days ended by the vicious lunge of a pig while he was making a TV documentary about medieval life introduced another theme that slithered on to my PC screen unbidden. But more about that in a tick.

One of the objections to a novel written in the first person is that it’s necessarily one-sided. You get by definition a single point of view about everything: the character and morals of other people, the details of recollected episodes in the narrative, and the albeit fictional reproduction of dialogue. It can become wearing, as the reader longs for others to have their say, especially about the narrator’s version of things. But it’s a change from the omniscient novel in which a soulless and anonymous narrator displays a phenomenal talent for remembering dialogue verbatim, for being privy to the thoughts and expressed intimacies of others, and for knowing exactly where the story is going. I mean, who is telling us about what goes on in Sense and Sensibility? Jane Austen, of course. But it’s not autobiographical and, even if it were, the recollection and reporting would be prodigious when they were not impossibly exhaustive.

So Notes From the Superhorse Stable is not a novel; it’s an eponymous set of elegant scribbles that does tell a linear tale but, like all notebooks or diaries, includes little that’s knowingly to the point or on track. That a reader or critic says a book could not be put down has always been to me a shortcoming rather than a virtue. When I put a book down it’s to consider and reflect on what I’ve just read.

In brief, Francis becomes interested in family history and discovers a long-lost relative, the former Welsh coal miner Harold Taylor, now living in retirement near Worthing. With his unstable partner, Julie, Francis starts visiting Harold and early on discovers that he (Harold) has newly-diagnosed cancer. An eccentric South Coast friend, Ethel Chrimes, wants to try an unconventional remedy developed in America. As Francis attempts to learn about his past from Harold, the present starts fragmenting and the future looks bleak.

Early on, Francis makes a pitch to the reader (assuming anyone else is going to read his Notes) or to himself about digression, the easy and satisfying tendency to wander off the main path. What one sees or thinks about in the byways is often an illuminating bonus. That’s what the process of making notes is like. What Francis probably does not notice at first but what I, his creator, clearly did is how there are links in the story he is telling; how for example, he played the lead horse, Nugget, in an early production of Peter Shaffer’s Equus and that one of the residents of the nursing home he’s working in is a former bookie called Bob Berridge, who with his help has written about the mysterious disappearance of the racehorse Shergar for an online encyclopaedia. Bob’s effort has a place in the book for a reason Francis explains. In fact, Francis does recognise these links but only on reflection: his first piece on excursus or parenthesis includes this realisation. Needless to say, the animal kingdom is everywhere in Notes From the Superhorse Stable and he makes no effort to exclude it. Why should he? It happened – magically and realistically.

This method of getting your narrator to deflect criticism of procedures has its pitfalls. My novel Slowly Burning, ‘written’ by a former tabloid crime reporter washed up on a Welsh weekly newspaper, is deliberately (on my part) littered with inconsistencies, misrememberings and inaccuracies in order that the narrator should conform to the image of an honest but imaginative and flippant hack. Some readers got the point, others didn’t pick up the solecisms at all. So much for realism. But trying something different, if not glisteringly new, in fiction is my faint tribute to the long-lost innovators of Modernism. Maybe they can be re-discovered, in the same way that Francis ‘found’ his relative Harold.

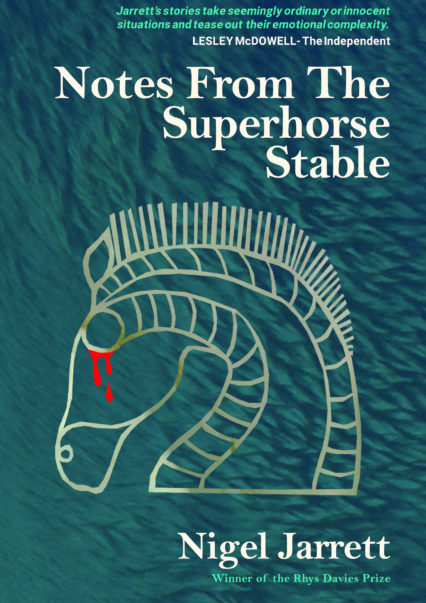

Notes From the Superhorse Stable by Nigel Jarrett is published from Saron Publishers and his available here.

Nigel Jarrett is a former newspaperman, a winner of the Rhys Davies Prize and the Templar Shorts Award for short fiction, and the author of six books. Notes From the Superhorse Stable is published by Saron Publishers, Slowly Burning by GG Books, both Welsh independents. This autumn, another Welsh indie, Cockatrice Books, is due to publish his fourth story collection Five Go to Switzerland. Jarrett lives in Abergavenny.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.