Unsurprisingly to the regular reader of Sean O’Brien, November includes a weighty contribution of railway poems, not so much a metaphor for journeys, but rather, simply, the jottings of another soul so taken by the stunning beauty of the railway line and the distant train. But O’Brien is distracted by a lot of things, not just railways, and everything he explores he does so with skill and intelligence, with wit and passion.

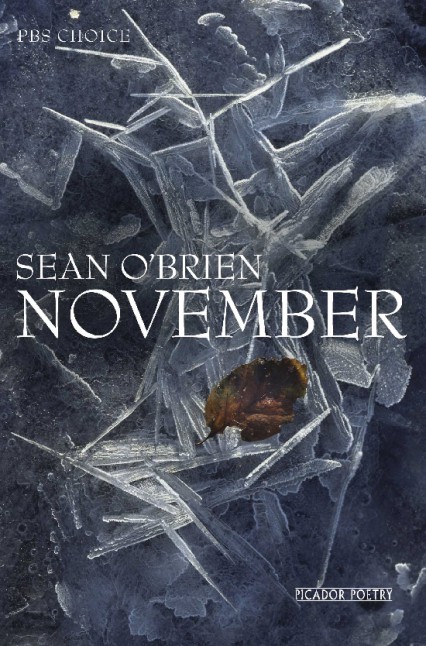

November is O’Brien’s seventh collection, his first since The Drowned Book, a collection that won both the Forward and T.S Eliot prizes, the first book to do so. Many of its themes will be nothing new for O’Brien fans but his exploration has stepped up a gear and this is where the book, written by a man remarkably attuned to his thoughts, mightily articulate while ceaselessly probing, gets its oomph.

The overriding matter is reflection, looking back with only the occasional glance forward, or ‘Staring back into a future from which she/Like us has vanished’ (‘Novembrists’). Although in some poems, O’Brien proves you can look back, forward, inward and out simultaneously, that grief should add a layer of meaning to a person’s life and not rot an existing one away.

The train poems show this trend most prominently, from the brief, ominous opening poem, ‘Fireweed’, ‘of strong neglect / In the railway towns, in the silence / After the age of the train’, to penultimate poem ‘Narbonne’, ‘No atlas could describe the distances that sound− / The train, the gust among the tiles and attics− / Offers us for nothing as it fades’.

by Sean O’Brien

82pp, Picador, £12.99

Then it’s the turn of the elegiac, though here, at times, O’Brien only has time for looking back, not exactly dwelling but not looking forward either. The collection is possessed by elegies, from ‘Where evening ends, and songs likewise, / And there is no one left to sing’(‘Leavetaking’) to “I studied you before the lid was sealed” (‘The Lost Book’). O’Brien was clearly distracted by deaths when writing November, not just the deaths of his friends and family but death as a fact, an unavoidable permanence. The poems start off with what the eyes see − a hearse, graves, priests − before developing to what the head can see − demons, gods and gospel − and finally settling on what O’Brien sees from the heart −faith, God, and, most appropriately of all, rebirth.

There is a lighter side to insight in the brilliantly quirky ‘The Plain Truth of the Matter’, using marmite to separate, presumably, believers from non-

Sean O’Brien doesn’t seem so much to be finding God or seeking redemption, but musing over the improbable but not impossible chance of reliving the past, not starting again but carrying on. The poem ‘Elegy’ and the collection as a whole is summed up endearingly by O’Brien himself: ‘a sick-