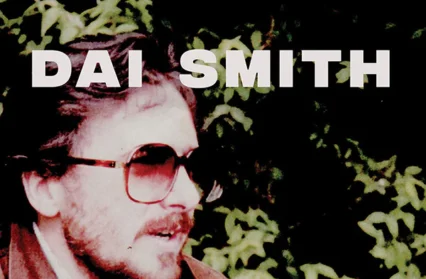

Huw Lawrence walks us through Off the Track, a weighty autobiography from the pen of Welsh academic, historian and literary stalwart, Dai Smith.

Off the Track follows Dai Smith from a childhood amid derelict collieries to old age, taking 400 pages, to which a short review can scarcely do justice. While one does not expect derring-do from an academic, it is nonetheless not boring – a long, eventful life and an oh-so-lucky one, in comparison with forebears. Before Dai Smith’s time, only a tiny number were granted an education, and they usually abandoned their class as a result – as did one in Dai Smith’s own family. “Just don’t become like Uncle Morris,” his father begs, when Oxford beckons. He needn’t have worried. The politics of equality took a grip on Dai. With hardly anything in the book about family or neighbourhood, leisure activities, hopes and desires, worries or secret fears, politics make this mainly an autobiography of the mind.

As Dai Smith entered secondary school, the family moved from Tonypandy to Barry, where he encountered a “Welsh-speaking elite”, an experience which produced a focus on class which would dominate from now on. The ability to speak Welsh was hardly a feature of privilege in the rest of Wales at that time, but Dai Smith resented Welsh as a primary feature of the comfortably-off group he found in Barry, In a school which “showed its mongrel town the civilisation to which it should aspire.” He found himself among those lower down the social scale.

More ambitious than rebellious, Dai makes a model pupil, his reading at this age nothing short of amazing. He wins a scholarship to Oxford, but it did not wreak its usual social change. Its accent and ways left no enduring marks.

From Oxford he wins a scholarship to Columbia in the USA, where he writes on Conrad, who “had moved from the earlier novels concerned with individual problems to an attempt to fix those problems in human society.” (p154). He never saw mere self-improvement as his goal but from early on entertained a vision rooted in industrial south Wales. He confesses that he sometimes “let the drivers for political change blur the complexity and variousness of human society.” That blurring also affected his view of Welsh society. He would more or less come to disregard everything of Wales north of Llanelli, becoming a south Wales focused universal socialist.

He leaves America after a broad tour which delivered him to San Francisco, “in the summer of love.” Would he wear a flower in his hair? No. He declaims against the cultural narcissism of the sixties, describing socialism as “a collective creed against despair” and Labour disputes as “paradigms of struggle.” We would have liked to hear more about this, but instead veer into stories about boxing, and about Lionel Trilling. “They knew who they were,” he writes of the Jewish Trillings, “and they knew there were times that bind and dues that had to be paid,” (p.163). Members of Plaid Cymru, a party soon to become his bête noir, could have quoted those words back at him as something they understood.

Despite his great antipathy towards Plaid Cymru, Dai Smith formed a close friendship with Carwyn James, who stood unsuccessfully for parliament as a Plaid candidate in Llanelli, and he likewise enjoyed a friendship with Gareth Williams, who taught History through the medium of Welsh at Aberystwyth. He was close to Meic Stephens, a life-long supporter of Plaid. Dafydd Elis Thomas, leader of Plaid Cymru, demonstrated side by side with Dai Smith against the lack of funding for English-language television and film, standing under a banner stating that ‘English is a Welsh language too’. None of these people turned their backs on him when he attacked what they most cherished. Eventually, he went too far and the press turned on him. His autobiography, almost half a century later, could have been the place to put all this to rights and make amends. Dai Smith dances away instead, with a quick jab – “linguistic nationalism” is an “essentialist view”. Well, who cares? He should have had something better to say than that for the sake of friendship.

By the middle of the book his attention shifts to the media, both to creative and administrative work. His academic work has by now become more tendentious and emotional and his interests increasingly veer towards literature rather than history. It is as if the study of history which – hand-in-hand with politics – had shaped his life, stopped being as strong a force. Disillusionment would be too strong a word. His interest shifts to drama and literature, where we feel we can understand his view of the Welsh novel in English. “Familial or melodramatic coalfield novels too often strained ineffectively for meaningfulness beyond the documentary reportage that was their undeniable strength, and their limitation.” Still, those authors knew who they were, and Dai Smith never lost his appreciation of that.

South Wales is at the centre of his considerable oeuvre, as it is of this autobiography. Meeting the relative of a friend, a war hero, he comments: “He was the epitome of what liberation into life might once have been in this place.” We are no less entranced than is Dai Smith himself by the character he calls, “the real Tom Jones.” Tom holds out his hand as they part, after an entertaining meeting (p.196): “Put it there, Dai. A pleasure to meet you. Shake the hand that shook the hand that held the cock that fucked Betty Grable.”

It’s not a boring autobiography!

This author, educated out of his original class, is determined to stay rooted. What different kind of class did we all of us form, educated, not a perfect fit any more with those we left behind in the places where our roots lay, we who remained fierce in our allegiance with those roots?

Speaking of his PhD, Dai Smith says: “I wanted to write meaningfully about the collective backstory and individual lives of the people and place from which I had come” (p.208). He did do that, for most of his life. Researching for his PhD, he amazingly perused mounds of newspapers, “a chaos of individual experiences,” yet with no idea of what exactly he was looking for. This was hardly a young man driven by worldly ambition. “Where is the X-ray of the whole culture and how do I take the picture?” he asks. Was there a residue of the Marxist belief that history has its own direction, historians its interpreters?

Dai Smith allies himself with Hobsbawn’s Marxist view of Welsh and Scottish nationalism, as “no more than ultimate political abdication” (p.248). He doesn’t explain this, but it does seem that anything other than universal socialism would be an abdication. For an understanding of Dai Smith’s politics, attend to the section called ‘Home Runs’. He had a generational hope and loyalty to what had been, or more accurately nearly had been. It was eventually defeated with the miner’s strike in 1985, finally extinguished later in 1986, at Wapping.

Today, nearly forty years on, if separatism brings about the break-up of the UK, as Dai Smith fears in this book, then the fault will lie with the concentration of wealth in England’s south-east, which has left houses to become holiday or retirement homes elsewhere across Britain. The Welsh are now a small minority in what was once called the ‘heartland’. The same is true the local population in parts of Yorkshire. It is true to a degree everywhere. What brought about the threat of break-up in the UK was not been the political allegiances of populations, it is population movement and change, and uncertainty, as driven by inequality and laissez-faire government at a bad extreme of capitalism.

Dai Smith lived through the historical final days of the working-class movement which he made the subject of his research. In 1980 he published The Fed (Miners’ Federation), co-written with Hywel Francis. His personal feelings came to govern his work so much that the historian Glanmor Williams told him pointedly that the next book, Wales! Wales? – wasn’t history. The early retirement of the memorable Gwyn Alf Williams must have left Dai Smith feeling something of a lone wolf in Cardiff University’s History Department, by then headed up by a devotee of Margaret Thatcher.

By the final part of Dai Smith’s story, any kind of working-class revolution is a long forgotten dream. Dai Smith moves from academia into television and on into the administration of the arts. He works on a television series made of Wales! Wales? He sees Wales from the mid-eighties as “bewilderingly floating” and contemplates putting himself up as a candidate for parliament. In his own words, “tendentiously ruthless” (p.236) he might have made a good one, if he could have got the votes – the autobiography’s solitary (and humorous) fragment of self-analysis compares him with Al Capone!

He agrees to write a biography of Raymond Williams, a work he was to complete years later. In 1993, he tells us he becomes the first non-Welsh-speaking Editor of BBC Radio Wales. In fact he grew up with the language, spoken at home by his mother and grandfather and he spoke it as a child at Sunday school. Later, in adulthood, he made himself proficient.

Moving on to chair the Arts Council of Wales, he recreated the old Academi under the new name of Literature Wales. He also appointed the first chairman of the National Theatre of Wales. He involved himself in making a film about his hero, Aneurin Bevan. As a commissioner with the BBC, his aim, he says, was to encourage Welsh audiences to value themselves. A falling out with the powers that be at the BBC took him to the University of Glamorgan, where he founded the valuable Library of Wales series, stalled later by bureaucratic disputes and policy changes. Can it fulfil hope and rise again? Most recently, he proffered a far-reaching perspective on Wales that looks back to before his own lifetime in a very readable novel, The Crossing, (Parthian 1990).

The autobiography portrays a character who doesn’t like constraint, who believes that art should be for its community, a character who applied himself to that out-of-fashion ideal called ‘the common good’. His contribution was rewarded with a CBE in 2017, for services to culture and the arts. Over the long period he has been among us, most of us have grown very used to him, some even fond of him.

Off The Track is published by Parthian Books and is available now.