Notes of Solidarity is a new daily series of mini-essays, poems, and reflections on the Russian war on Ukraine by some of Wales’s leading literary figures. Here, poet and broadcaster Paul Henry explores the power and threat of poetry with work from Joseph Brodsky and Anna Akhmatova

Joseph Brodsky’s quietly heart-breaking essay, In a Room and a Half, recollects weekly phone calls in the 1970s, from his involuntary exile in the West to the Leningrad tenement where his ‘state-resistant’ parents remained. Conscious of third parties listening-in, both son and parents resorted to the ‘oblique and euphemistic’ in their talk. ‘The main thing was hearing each other’s voice…’. How that line resonates today. The love is in the ‘hearing’.

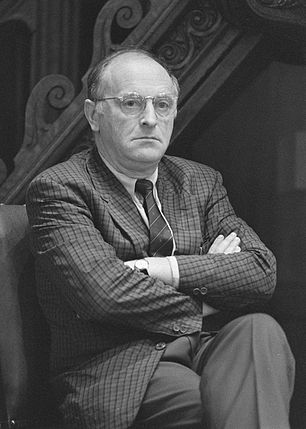

I spent a week with Brodsky in 1992, at the Hay Festival. By that time, Poetry – the ‘social parasitism’ that had provoked his sentence of five years’ hard labour in Northern Russia – had become his homeland. Recovering from a third heart operation, he pecked at salads between cigarettes, stared into the unwritten distance. One of his favourite poems, the titular subject of a masterly commentary, was Auden’s ‘September 1, 1939’. May its most famous line cross Putin’s cold eye:

‘We must love one another or die.’

Fifteen years on, in a bar in Vilnius, I was reminded again of Poetry’s threat to oppressive regimes. I’d just read with the Lithuanian poet and translator Laurynus Katkus, at the amazing ‘Druskininkai Poetic Fall’ festival. Laurynus and I were exchanging slim volumes. I think I got the better deal. Designed by fellow poet and artist Tomas S. Butkus, October Holidays, Laurynus’s fawn, featherlight pamphlet, had an integrity. He explained that, under previous Soviet rule, in a censorial climate where writers and journalists would sometimes ‘disappear’, such modestly clothed pamphlets had become almost de rigueur. I keep it behind glass, open it now, on a poem called ‘Gudžioniai Rhapsody’, try to hear the voice through translated lines. A poem marking the end of a holiday becomes weighted with Ukraine’s nightmare:

‘We are leaving. The flies on the ceiling stop buzzing,

blankets, lamps, knives, shuffled under the beds,

keep silent. It’s grown dark as a Saint’s eyes.’

The Keening Muse, another Brodsky essay, celebrates his mentor, Anna Akhmatova, who lost two husbands to Stalin and whose son, Lev Gumilyov, was unjustly and repeatedly incarcerated in concentration camps. Akhmatova’s personal torment became universal in her acclaimed poem-cycle, ‘Requiem’:

‘I would like to call them all by name,

but the list was taken away and I can’t remember.For them I have woven a wide shroud

from the humble words I heard among them.’

It was 1963 before ‘Requiem’ was published, though it was written two or three decades earlier. Too dangerous for the page, much of Akhmatova’s poetry was drafted on air, memorized by the poet and friends. Brodsky applauds how ‘a poet of human ties: cherished, strained, severed’ gave voice to millions, ‘first through the prism of the heart, then through the prism of history…’.

Fifty-six years after Akhmatova’s death, let us applaud then, at this dark time, the courage of all Eastern European poets, amongst them Aleksey Porvin, whose unwritten distances will add to her legacy.

Paul Henry Paul Henry

For more information on the Russia-Ukraine war, including ways you can help, please click here.

You can follow all contributions to Notes of Solidarity from Wales Arts Review here.