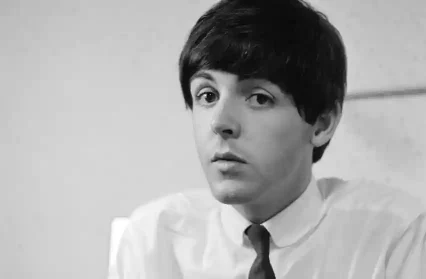

Gary Raymond pays tribute to the genius of Paul McCartney on the day of the great songwriter’s 80th birthday.

Paul McCartney was my first gig. Earl’s Court, September 14th, 1993. I was fourteen years old, and my dad treated me, presumably to provide some kind of apex to my ongoing Beatles obsession. It worked. The band were in my bloodstream. I had, until my dad bought me a guitar for my thirteenth birthday, spent many an evening after school singing along to Beatles records with my tennis racket standing in for a Rickenbacker (I hit more woooooos with that racket than I ever did tennis balls, no doubt about that). So, yes, Paul McCartney, in 1993, was my first gig. It’s strange to imagine it now, but for a long time that was not the coolest thing in the fucking world. In the nineties, McCartney’s stock was low amongst a generation of music writers and music makers. That he hadn’t made a decent album in over a decade was the least of his problems. Nobody ever dared diss The Beatles (apart from Jarvis Cocker, I remember, who was once quoted in a music monthly mischievously claiming Sgt Pepper… was the worst album ever made), but the solo work of the surviving members was the music of a different generation to the arbiters of cool who had found and founded their platforms in the indie post-punk revolutions of the 1980s. And few at the cool table were ever going to forgive McCartney for the frog chorus, a crime many had viewed as usurping “Mull of Kintyre” in the short but potent list of McCartney’s crimes against culture. Also not cool in 1993: vegetarianism. Again, difficult to believe in this day and age, but McCartney’s devotion to animal rights made him the focus of much mockery for decades.

The album McCartney was touring in 1993 was the underwhelming Off the Ground. It is a record full of youthful energy, and McCartney had benefitted from a new tight band of exceptionally accomplished jobbing musicians (including Robbie McIntosh formerly of The Pretenders and Average White Band founding member Hamish Stuart), who helped him create the songs in the studio and then take those songs on a back-breaking world tour. Unfortunately, with the odd exception, there are more than a few duds on listening back, and none more duddy than “Looking for Changes”, an animals-rights protest song that includes the lyric “I saw a cat with a machine in his brain/ The man beside him said he didn’t feel any pain/ I’d like to see that man take out that machine/ And stick it in his own brain / You know what I mean?” McCartney has always humbly claimed himself to be a poor lyricist (from the man who wrote “For No One”!), but this is a stinker. (On that album, see also “Biker Like an Icon”; to be filed under “sounded like a good idea at the time”).

Just a few years later, Britpop would come along and reignite a love of British pop music of the mid-to-late-sixties, an era for which McCartney was obviously central, if not the absolute king. But in that revivalist age, McCartney remained elusive if not largely ignored. As Oasis salvaged what they wanted from the Armadas of the past, it was quite clear their allegiances truly rested with John Lennon. They, like so many of us, had responded to the myth of Lennon’s attitudes and creative impulses. That he was the working-class hero, that he was the experimenter, the iconoclast, the rebel without a cause. For those paying attention for these last few years, that has been rewritten. Ian Leslie’s essay on McCartney from 2020 is an essential breakdown of what we owe McCartney. Craig Brown’s Beatles biography, the best of the many I have read over the years, also realigns the dynamic in the band. Peter Jackson’s Get Back provides documentary proof those dynamics are as faithful to the true course of things as it’s possible to be. It may have taken until his late seventies for McCartney to begin to receive the credit he deserves, but, by God, at least we haven’t left it until he’s dead. That would have been shameful.

But yes, in 1993, ex-Beatle, writer of “Yesterday” and “Hey Jude” and all those other songs that have become part of the furniture, was not very cool. So, when asked “what was your first gig?” for years to come, my answer would be met with respect – he was a Beatle, after all – but it was also met with dismissal, because others could answer Manic Street Preachers, The Wedding Present, or… I dunno… the bloody Comsat Angels. For years, I was surrounded by drinking buddies who refused to forgive McCartney for “The Long and Winding Road”, never mind the bloody frog chorus.

The narrative went: McCartney was the melody man, the softie, the pop guy, the panderer, the populist, the eager-to-please (nothing less cool than being eager to please, after all). The narrative also had him as the posh boy – or the middle-class soft boy, anyway. When I was a kid, this kind of nonsense had led me to just assume – despite what I could hear with my own ears – that “Helter Skelter” belonged to Lennon, because, obviously, Paul McCartney, soft boy, could not possibly have invented Heavy Metal. McCartney could not be cool, could not be funky, could not be bluesy. That was Lennon. Now we know, just about, the full breadth of McCartney’s genius. Now we listen to his solo output and realise it is often as good as anything The Beatles ever put out. Just this morning I was reminded when listening to a track from the 1979 Wings album, Back to the Egg, “Arrow Through Me”, just what a supremely instinctive funky songwriter he could be. The brass riff is as dirty as anything Stevie Wonder ground out in that period. But still the song retains some melodic sensitivities most songwriters would be incapable of embedding. And that song wouldn’t trouble a list of McCartney’s top 100.

Wings, for a long time, was a byword for that populism McCartney was accused of. Indeed, so misguided is much of that criticism, so dismissive and condescending, of McCartney’s prodigious seventies output, you have to wonder if anybody was really listening to these records before writing about them. “Mull of Kintyre”, condemned mostly it seems now for the inclusion of bagpipes (and on this point I am happy to concede ground to the critics), cast a heavy and long shadow. When McCartney transgresses, he is shown no mercy. Perhaps he was getting flack still for having broken up The Beatles and forcing Lennon into a decade of mundanity and posing (with sparks of his previous, McCartney-chaperoned genius). In the press pack for his debut solo album in 1970, McCartney stated he did not see a time when he would write with Lennon again. Lennon, however, had told the other Beatles he wanted a “divorce” seventh months earlier. The irreconcilable difference in the band was the Lennon-Harrison-Starr desire to have Rolling Stones manager and generally regarded crook and uber-bastard Allen Klein manage the band. McCartney, however, wanted Lee Eastman, New York showbiz attorney and dad to his wife Linda. Undoubtedly, McCartney had the better idea. Lennon, corralling the other two, had had one too many drunken conversations with Mick Jagger about Klein. The irony of Lennon being envious of what the Stones had, the band who owed most of their success to the footprints The Beatles had left for them, was not something that McCartney had much heart for.

But for a time, McCartney was second only to Darth Yoko in the responsibility stakes for who killed The Beatles. There is no doubt he was resented for it. In truth, McCartney lost The Beatles, he didn’t break them. Arguably, he was the band leader from the moment they hung up their touring suits and was quite likely the most pragmatic and business-minded of them from the off. It was McCartney who was the working-class kid with eyes on a better life. Lennon, the middle-class “orphan” with catastrophic mommy-issues, was First Mate from the moment his nervous energy couldn’t be channelled into an exhausting live schedule. Harrison was drifting on a more celestial plane in the last sixties, and Ringo, for all of his talent and percussive innovations during his Beatles career, continued to look around half-expecting to be awoken from this best-possible life dream any minute now.

After 1966, McCartney was The Beatles. The evidence is all there. Lennon did not make one good album as a solo artist. In fact, you could likely make one great album from his best output of the 1970s. Harrison released All Things Must Pass in 1970 and its strength is largely in the wealth of stockpiled songs he couldn’t elbow past the Lennon-McCartney gatekeepers and onto a Beatles album. Harrison went on to prove himself a wonderful writer, but the period between 1974’s Living in the Material World and 1987’s Cloud 9 has some embarrassing low points. McCartney was likely the best songwriter of the 70s, as well as of the 60s.

McCartney the experimenter cannot be hidden once he’s out of The Beatles. Although it is there throughout the 1960s (you can go as broad as the evidence that McCartney was the creative impetus behind the White Album’s lengthy collage “Number 9 Dream”, previously seen as Lennon’s experimental opus, to the sheer elating genius of the structural embellishments of something as deceptively simple as “I’ve Just Seen a Face” from 1965), nobody can mistake his work for that of the maverick Lennon on left turns from his solo debut like “That Would Be Something” or blues blasters like “Oo You” (which I undoubtedly would have mistaken for a Lennon track had it been released a few months earlier).

That debut, McCartney, became the first of a decades-spanning trilogy of “home recordings” where McCartney played every instrument, as well as produced and engineered the records entirely. For the second of these, McCartney II in 1980, he was still putting up hit singles like “Coming Up” (where McCartney rides out a rhythm section Sly Stone would have envied) and melodic masterpieces like “Waterfalls”, but now he was also constructing electronic novelties in “Temporary Secretary” that would find a new lease of life in DJ sets at new wave nightclubs from Glasgow to Brighton. McCartney III, recorded during lockdown and released in 2020, is connected to the previous two by its DNA, as a complete McCartney project, no session players, no outside producer, a writer and performer locked away, intense and focused. It is a different record, however, in that this is the statement of an elder statesman, albeit one with indefatigable boyish energy. On McCartney III he is cool again. The world has caught up with him. We know the truth of the dynamic with Lennon. That he has been a vegetarian since 1975 speaks volumes. I don’t think my local pub, full of haters of “The Long and Winding Road”, had a veggie burger on the food menu until 2016.

In the gaps between I, II, and III, McCartney has been writing some sublime songs. About five years ago I went back to his 70s output, previously having been railroaded into thinking there was nothing of interest there by the Lennonites and others who had been similarly misguided. So many of us, for so long, thought he had a fluke renaissance with Band on the Run (1973) and that was that. What you can hear, however, in the albums of Paul McCartney in the first half of that post-Beatles decade, is an artist searching for an identity in one sense, but also – now we can look so far back – an artist resplendent in the roaming freedom of his ideas and his opportunities. He may have been depressed and drinking too much, but in the studio he was as free as a bird.

We always used to think the shackles of Lennon being unlocked meant he went to places self-indulgent and sentimentally reckless. But now we see music has its time. Take the first Wings record, for instance – that’s right, Wings: the poppy, safety mechanism that McCartney supposedly constructed around himself so he could pretend The Beatles never broke up. Wild Life (1971) is a superbly raw and intimate album that sounds very much like what was it: a bunch of guys jamming around. Not so much they were having a great time, because McCartney was depressed and drinking too much, but still, it’s an album that sounds like a band hanging out. It also contains two McCartney career highlights. His best activist song is the album’s title track. And the reggae cover version of Mickey & Sylvia’s 1957 hit “Love is Strange” is one of the finest cover versions by anyone in an era, full of cool passion and loose expertise.

The other albums of that prodigious few years, Ram (1971), Red Rose Speedway (1973), and Band on the Run (also 1973) are packed hard with songs good enough for Beatles albums. And most significantly, they have the sonic DNA of late Beatles recordings, suggesting there was more McCartney in those albums than there was Lennon, Harrison, or Starkey. And that DNA can still be found today. Okay, so the recording techniques have come on a bit, but McCartney still loves that live studio sound, those open drum sounds, the hacking brilliance of his southpaw lead guitar playing that wouldn’t be the same with a ProTools clean up, and his bass still pops and runs and fills a pop song like it’s the lower movements of a symphony. McCartney is a genius, and there may have been more than one genius in The Beatles, but he was the main one, the king of the gods, the once in a century, our Bach, our Beethoven, our Mozart.

That he is now appreciated widely in these terms is a blessing. Imagine if Rick Rubin had had the chance to sit in with any of those three guys I mentioned above in the way he did with McCartney for Apple TVs McCartney 3,2,1 last year, picking apart The Goldberg Variations or Moonlight Sonata with their composers. Well, we have that for McCartney. Generation after generation will be increasingly grateful.

As for me, that gig in ‘ninety-three was a formative game-changer. I couldn’t really take anything seriously that wasn’t about music or writing after that. McCartney had made eye contact with me at one point and it confirmed that the Beatles was my band, that he had written all those songs for me. As a boy from a council estate in south Wales I was pretty much done for. There were no careers that fitted that bill on offer to me. In school I spent my lessons scrawling song lyrics on my exercise books, drawing fictitious bands on cartoon stages, and designing logos for bands I hadn’t started yet. I had been broken by the power of rock n roll, and the breaker was the greatest of them all. I remember the programme for that gig offered a substantial discount on Mark Lewisohn’s ground-breaking study of The Beatles’ complete itinerary of concert touring and studio sessions, The Complete Beatles Chronicle, and at Christmas, when it turned up under the tree, I graduated from musical acolyte to nerd amateur historian extraordinaire, and after a while I was able to piece together that The Beatles concert my dad attended at Cardiff Capitol in 1965 was the last before their ill-fated world tour, then one that would prove their last – so my dad was at The Beatles’ last British gig. (My mother, a Liverpudlian, had seen The Beatles in The Cavern Club a few times and used to get a bit of a kick out of telling me she thought they were rubbish). It remains an event for which I retain an unusual amount of clarity. McCartney being lifted on a crane above our heads for his rendition of Let Me Roll It; the Psychedelic honky tonk for “Magical Mystery Tour”, the silence for “Yesterday”. My dad remembers in 1965, “Yesterday” was the only song he heard, so ferocious and unrelenting was the mania from the audience that evening. Everybody shut up for Paul and his acoustic guitar. The reason why McCartney is so good, is because he is a simple man, honest and open and uncomplicated in his reflections on his life. He does not try to dazzle or bury his craft in esoterism or mythology. When he’s channelling Bach he knows who it is he’s channelling it to. He is a working-class boy done good, but he’s still working-class. Writing an oratorio doesn’t run that out of you, and neither does a frog chorus, and neither does a chorus of bagpipes. I firmly believe that his genius was overlooked for decades because it is such a simple thing to recognise. He writes great songs. Great songs. And there’s really not much else to it.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, critic, and broadcaster, and is executive editor of Wales Arts Review.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.