Wales Arts Review asked some of Wales’s top writers to pen some thoughts on the future. This new series brings together a wide variety of perspectives and ideas in a vibrant array of styles and forms, expressing hopes for a new way of doing things when the Covid-19 coronavirus is finally overcome. Political, personal, sociological, ecological, cultural – this is an evolving tableau of ideas. Here, Peter Finch walks an eerie Ballard world of lockdown and sees hope in a renewal of the way society interacts.

At intervals, when the sky was overcast, the water out in the distant bay was almost black, like putrescent dye. By contrast, the straggle of warehouses, high rise apartments and shining hotels that constituted the capital city gleamed across the dark swells with a spectral brightness. It was as if they were lit less by solar light than by some interior lantern. They were like the pavilions of an abandoned necropolis built out across the barrage and along the edges of the coastal plain. Cardiff in lockdown.

I’ve climbed Penylan Hill, running up along Bronwydd where the gardens are still full of trees, and other than the birds there isn’t a sound.

A short way ahead I pass an open front door. Pushing back the gate I walk up the path to the porch. All is still. Hidden by the shade I glance up and down the empty street. Through the door I can see into the living room and the kitchen. Cardboard cartons are stacked in the hall and unwanted suitcases lie across the armchairs. Above the sky remains a bland limpid blue, devoid of all cloud. In the large rear garden white plastic stacking chairs are in disarray and the empty swimming pool lies abandoned.

A short way ahead I pass an open front door. Pushing back the gate I walk up the path to the porch. All is still. Hidden by the shade I glance up and down the empty street. Through the door I can see into the living room and the kitchen. Cardboard cartons are stacked in the hall and unwanted suitcases lie across the armchairs. Above the sky remains a bland limpid blue, devoid of all cloud. In the large rear garden white plastic stacking chairs are in disarray and the empty swimming pool lies abandoned.

There are no planes. I check my app. In the past this would show Wales a mass of tail fins and flight route labels. But today there’s only a single helicopter over Anglesey and that is vanishing towards Ireland. Everything else is that vacant translucent blue.

Ahead in the distance billows of white smoke mushroom over the roofs, followed by tips of eager flame, almost colourless in the hot sunlight. There is still no sound. Rhigos fire has burned now as far as Caerphilly and is threatening to lick its way on south. No one cares. You light it for something to do. Eventually it’ll touch these streets and then fizzle at the edge of the Cardiff sea, that which remains. The shrinking world spilling off into a flat and endless two dimensional space where the dragons are.

I should be out there, where the fire started, exploring the Valley trails in places I don’t know that well, mapping what remains of our industrial past before it gets forever mashed by the constantly arriving future. The new world where no one speaks to you because there are just too many of us to do that. You can’t acknowledge them all so you acknowledge none. Stare ahead, walk straight on.

In Rhymney, where I was trailing the streets most recently, a place that is referred to as Mordor by those living back down the valley in the big cities of Bargoed and Hengoed and Caerphilly, I was called but three times in my first twenty minutes after disembarking the train. Streets where everyone smiled and spoke. Cafes where they asked after your health and wanted to know why you were here and if there was anything they could do to help. Back home in the capital no one says a thing. No one smiles. Unless they are out to hassle you for something no one ever catches your eye. Our big city socialism stutters. You can get from City Hall walking all the way out to the Culver House in the west without having a single word addressed to you directly. I’ve done it. I smiled. They didn’t. I gave up.

But somehow this Covid seems to have fixed all that. Up on those streets high on the hill where money used to reside before it moved out further to Lisvane people now shout greetings from right across roadways, move smiling to let you pass with your wide berth as big as their wide berth. Only the sweating runners fail to bother.

Face down in a shallow hollow at the edge of the ridge where Ty Gwyn beaches itself onto Cyncoed Road I watch the white-hulled sand-car of the time wardens shunt through the darkness along the old parish boundary. Directly below me jut the spires of the newly discovered tomb-bed invisible against the background of the ridge. Next to the wrecked observatory the abandoned water tower with its silver statue points up at the starless sky. The childless play park is ribboned off with wind-trailing warning tape. The synagogue in the distance is as worshiper-free as the churches down the hill. We are waiting for the world to end, some of us. Others know that it will rise again.

By evening youths begin to cluster under trees, holding their skateboards as if they were ceremonial weapons, smoking quietly as the dusk strengthens. A sepulchral light lies over the concrete shelters. Among the abandoned mausoleums along the edges of the boating lake I see the figures of friends I’ve not seen in the flesh, Zoom excepted, for months now. They have been watching me for hours. They don’t move but I’m sure they are beckoning me. I don’t go.

Up on the mezzanine, I stand by the cracked plate-glass window beyond the tables. Already half submerged by fear, what remains of the city seems full of fractured dimension-shifting glass. It is as if space itself were compensating for the landscape’s loss of time by forcing us into a bizarre warp. The world hovers waiting for time to move again. Running out of things. Shivering. The guardians fading slowly from view.

Some thought that this gap in time’s fabric through which we are currently passing would present the nation with an opportunity to create its greatest works in millennia. There would be towers, great bridges, cures for age old diseases, successful debates on the needs to end poverty and inequality, a common agreed direction towards the light, new novels that would define what we are and poems that would electrify the soul. Through the growing mists experts kitted out like tv presenters pointed to moving shapes as proof that these things were actually happening. Maybe they were.

I suppose this whole series of unnerving episodes would eventually have disappeared but for those presenters each night ramping the fear to new heights. On those evenings when technical failure didn’t prevent their appearance they showed charts. There were about twenty of these in all. Wavering lines climbing like the bent legs of spiders fed by half a million data collection points spread across the four nations. One was marked with what I assumed to be symbols for death, another showed rebirth. There were reds and imprecise blues. Hard to discern in the flickering light.

On the coastal plain where in earlier times of eco panic it was feared flood waters would breach the sea wall to fill basements and fuse power stations the factories were being repurposed. The one making solar panels had turned its attention to producing ventilators. There was a warehouse filled to the roof with new product, none of it yet authorised as approved for use. Towards Newport a former chemical factory had begun to research machinery that would bend time. If they could get it to imitate the leg lines of those spiders maybe things would improve.

I still suspected that I was getting myself wound up over nothing. The exit was actually just ten miles away, wasn’t it, or maybe that was ten hundred I couldn’t be absolutely sure. The terrain was rough now. I could see rolls of fog slowly billowing ahead. But we’d make it. Of course we would.

Check out the other articles in Wales Arts Review’s ‘When This is Over’ series.

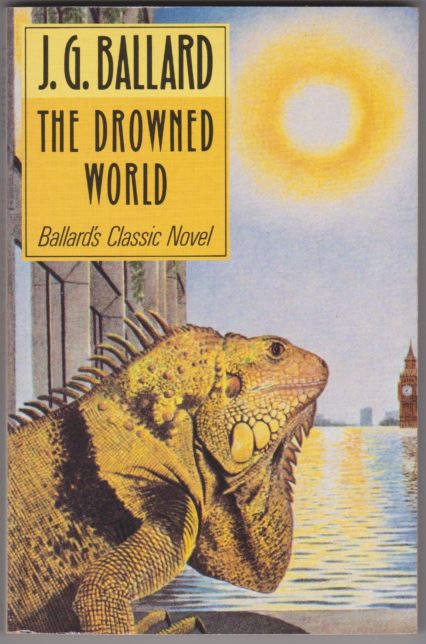

Sources: J G Ballard’s The Crystal World, and The Drought, my paperbacks from 1968, white pages with nicotine edges, copies slowly breaking along their spines. Ballard’s The Complete Short Stories, still bright clear white from 2002. Ballard’s world was entirely like the one out of all of our windows right now.

Peter Finch is a full-time poet, psychogeographer, critic, author, rock fan and literary entrepreneur living in Cardiff, Wales. Until 2011 he was Chief Executive of Literature Wales (formerly The Welsh Academy), the Welsh National Literature Development Agency. As a writer he works in both traditional and experimental forms. He is best known for his declamatory poetry readings, his creative work based on his native city of Cardiff, his editing of Seren’s Real series, and his knowledge of rock and roll.