Petrol is described by Martina Evans’ publisher as being ‘a prose poem disguised as a novella’, and this is true in the sense that it is possible to think of works such as Ulysses or The Waves as being prose poems disguised as novels. Such definitions ultimately matter little but I mention these distinguished works to give a sense of the type of hard-to-define territory Evans seeks to inhabit. She is a writer who, much like the Scottish novelist and short story writer, Ali Smith, prizes and returns to the modernist project, sensing that stream of consciousness is not an outmoded and discredited technique but rather one that is admirably suited to the sensual overload of contemporary society. It is a technique, which can perhaps best allow the writer to describe the feelings and sensations of events. It is a way, in the words of Hemingway, of ‘conveying experience to the reader so that he or she has read something that will become a part of his or her experience and seem actually to have happened.’

The epigraph to this prose poem/novella (which, just to continue that sense of disregarded stylistic barriers, is preceded by a dramatis personae), is a deeply appropriate quote from Alice in Wonderland:

‘But I don’t want to go among mad people,’ Alice remarked.

‘Oh you can’t help that,’ said the Cat. ‘We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.’

Imelda, the thirteen year-old narrator of Petrol, lives in such a world. It is partly that, to her child’s eye view, the adult world seems bizarre and inexplicable but there is also the strong sense that the madness of the world as a general condition is an abiding principal of Evans’ outlook as an artist. This is a book which teems with vivid details of seventies Ireland whilst at the same time describing reality as a dreamlike melding of the present moment with memory and imagination:

It wasn’t that dark with the lights from the cars outside and the glow from the Major Cigarettes sign lighting up the page but sometimes the mice wouldn’t stop running inside the panelling and there was the strange smell from the possessed girl’s room in The Exorcist and having to go to the bathroom and passing Mammy’s grotto where the cabbage-green snake was biting the Virgin Mary’s foot and I was always afraid Mammy’s ghost would appear to me above the green linoleum stairs.

This paragraph, describing Imelda’s too-early-bedtime of eight o’clock, is an excellent example of Evans’ technique in action. She sets an evocative scene of a scared-of-the-dark-girl lit by carlight and neon and then runs without pausing for breath into the sound of mice scrambling about behind the wall. She then seamlessly – still breathlessly – interweaves dream reality into the picture, just as it interweaves its way into the fearful girl’s darkdulled perceptions. She can smell the ‘strange smell from the possessed girl’s room in The Exorcist’ – a film she must have somehow snuck into see with her older sisters, possibly under duress as one of them forces her to watch Night Gallery, a TV horror series, later in the book – in that way that children’s overactive imaginations can smell things which have impressed them but which they have, in fact, never actually smelt. The smell is no doubt the smell of the green gunk that poor Regan McNeil spews out in that film, something which interlinks with Imelda’s fear of the ‘cabbage green snake’ at the foot of the statue of the Virgin Mary on the landing. That and to the root fear that her dead mother will appear to her ‘high above the green linoleum stairs.’

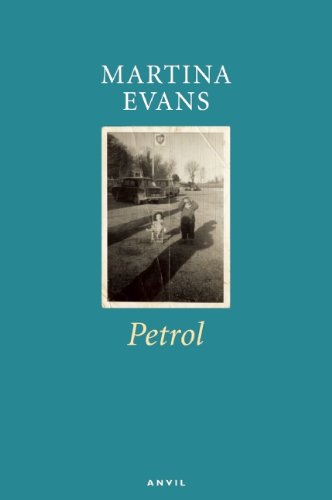

by Martina Evans

pp. 68. Anvil Press, £8.99

If we take into account that the BP petrol sign outside her window is also predominantly green then we can see that we are in the midst of a sensory overload of this particular colour. Green for what? For envy? For nature? For the supernatural? For danger? For illness? For youth? For Ireland? All of these things have relevance to the young Imelda who is convinced she murdered her mother by simply wishing her dead. The young Imelda whose two older sisters appear to be in a constant state of jealousy and envy, which indeed, seems to be the state of the entire town (might it be too much to say the state of the entire, sexually repressed world of seventies Ireland?) She is also green in that she is young and naïve and at the beginning of a sexual awakening that will see her fall in love with a nineteen year-old farmer.

But perhaps the overriding sense is that we are, much like the prose itself, in a kind of woozy, half-awake/half-asleep, in between place, where the unreal, the supernatural even, can appear vividly actual. In this sense Evans appears to be deliberately echoing Hitchcock’s use of green in Vertigo, where Madeline-doppelganger Judy appears constantly wreathed in green, both in terms of clothes and neon lighting. Judy who almost seems like the ghost of Madeline such is her resemblance to the dead woman. This kind of fever dream green glow lights much of Imelda’s thoughts, a young girl after all, who has just lost her mother.

Viewed in that sense Petrol could be seen as being, like Vertigo, primarily about grief. But in fact it is primarily concerned with a confluence of emotions and sensations. It is interested in describing that moment when adolescence really hits you with a bang. When the adult world is suddenly something which is relevant to you. When finances and responsibility and sex and death are all things which suddenly apply to you, at the very time that your body is changing and distorting all of your senses and emotions so that your heart feels like it’s in your knees. This is the world of Petrol, the strong, cheap smell of that substance permeating these pages like the very odour of adolescence. Evans needs her in-between language to fully evoke this mind state and it’s something she fully utilises, garnering poetry from prose in a way that, by the book’s end, makes you think that, Oh yes, that really was ‘a prose poem disguised as a novella’!

Why? Because by the book’s close, when ‘the BP sign creak[s] and creak[s] like a horror in the wind’, all of its cumulative resonances lift and shake you, placing you for a moment somewhere higher. Placing you for a moment on that ‘highest terrace of consciousness’, that Nabokov talks of in Speak Memory. ‘Where mortality has a chance to peer beyond its own limits, from the mast, from the past and its castle tower.’