The title of Clive McCarthy’s exhibition at the Kickplate Gallery, Abertillery, might qualify as the supreme example of self-effacement. When asked what it refers to, the Newport-based artist will say it describes not his work, and especially not the exhibits in this show, but rather his place as a maker of that work in a province never short of bloated egos and stereotypes of one kind of struggling creative or another. McCarthy studied for his BA at the former Newport College of Art when it was still regarded as one of the three most important UK art schools outside London, and then went on to take a Masters in Graphic Illustration at Birmingham Polytechnic. His college generation at Newport followed on from artists such as John Selway, Jefferey Steele and Osi Rhys Osmond, who later made international reputations.

For reasons that don’t concern us here, McCarthy was a relatively late starter. Although he taught a few classes in drawing at Newport after completing his studies, he eschewed teaching as a career, instead opting for a series of skilled manual jobs to support himself and his family while continuing to paint and sell pictures. Latterly he worked as a ceramic technician on ships, renovating their boilers while at sea or dry docked, often in foreign ports and almost always in hazardous surroundings. As an artist, he’s therefore never felt that the world owed him a living. Insofar as few artists are prepared to do that – to work at unrelated tasks while pursuing the role of a professional – he’s possibly the very opposite of ‘insignificant’. What he’s done and how he’s gone about it signify a lot. To watch him plastering a wall – he’s a dab hand at painting and decorating – is to witness an artist at work in more than one sense.

For reasons that don’t concern us here, McCarthy was a relatively late starter. Although he taught a few classes in drawing at Newport after completing his studies, he eschewed teaching as a career, instead opting for a series of skilled manual jobs to support himself and his family while continuing to paint and sell pictures. Latterly he worked as a ceramic technician on ships, renovating their boilers while at sea or dry docked, often in foreign ports and almost always in hazardous surroundings. As an artist, he’s therefore never felt that the world owed him a living. Insofar as few artists are prepared to do that – to work at unrelated tasks while pursuing the role of a professional – he’s possibly the very opposite of ‘insignificant’. What he’s done and how he’s gone about it signify a lot. To watch him plastering a wall – he’s a dab hand at painting and decorating – is to witness an artist at work in more than one sense.

Part of his output might suggest that McCarthy is not so much a figurative painter as a documentary realist, one grounded, as many of his generation were, in rigorous draughtsmanship. Those years cooped up in the dark and suffocating innards of ships resulted in some vivid maritime pictures. When he wasn’t inside the bulkheads he kept his eyes focused on the surroundings, painting and drawing dockland scenes as well as the ever-changing seas and skies while afloat. (There exists a photograph of him on deck, a large drawing board on his lap, as he takes a break to record what the weather is up to while, one assumes, others on board are trying not to throw up as the ship dips and rolls). His maritime pictures formed the basis of his last big show, held at Southampton Metropolitan University to mark a celebration of that city’s long association with the sea.

Part of his output might suggest that McCarthy is not so much a figurative painter as a documentary realist, one grounded, as many of his generation were, in rigorous draughtsmanship. Those years cooped up in the dark and suffocating innards of ships resulted in some vivid maritime pictures. When he wasn’t inside the bulkheads he kept his eyes focused on the surroundings, painting and drawing dockland scenes as well as the ever-changing seas and skies while afloat. (There exists a photograph of him on deck, a large drawing board on his lap, as he takes a break to record what the weather is up to while, one assumes, others on board are trying not to throw up as the ship dips and rolls). His maritime pictures formed the basis of his last big show, held at Southampton Metropolitan University to mark a celebration of that city’s long association with the sea.

A couple of large watercolours of Southampton’s wet dock are included in his Abertillery exhibition, one of them almost painfully detailed. A sweep of the location reveals, on one side, scrap metal waiting to be exported and, on the other, a mountain of wood pulp being unloaded from a ship called Sea Melody. The picture is typical of McCarthy’s refusal to entertain any triumph of panorama over particularity, the particular deriving from personal experience and thus accorded the dignity of being unambiguously set down. In the other, only perspective allows him to paint receding piles of scrap with less detail than their rococo foreground, which must have taken him ages to complete. It’s a shame that space did not allow him to show how his near-abstract fastnesses of sea and sky envelop whatever is happening beneath, a case of realism almost swamped by a romantic sense of something bigger, wider and more spiritual; but there’s enough to give an inkling. That said, and comparing McCarthy’s scenes with the more concentrated and specific efforts during wartime of Stanley Spencer and Edward Wadsworth in similar places, some might find an ambivalence in this contrast between narrow focus and extension. In our more charitable moments, though, we might ascribe their appearance to a need to make vision all-embracing.

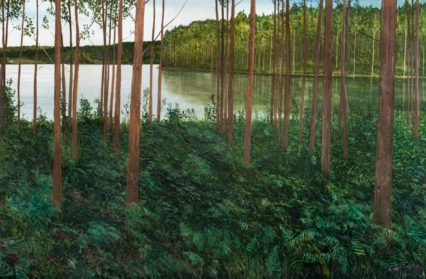

Attention to minutiae is apparent elsewhere; for example, in Woodland Scene, a Klimt-like composition drawing the eye not to distances but to foreground surface interest, in this case meticulously rendered vegetation. Bearing in mind that these ambitious compositions are executed in watercolour, one might expect more broad-brushed wash than pinpoint accuracy. But, for the purposes of this exhibition at least, McCarthy is a draughtsman in paint. Even in the last of the bigger pictures, Woman With Cat, large swathes of colour limited in number contrast with the subject’s anatomical components, almost comically applied. One can imagine that the artist spent a deal of time deciding where to place the animal, eventually opting for a position that reflects both pictorial and feline independence. More than that, the picture is part of the show’s new work, a departure embracing wit and what appears to be whimsy. It’s characterised by the horizontal Tin Toy Series of paintings, in which objects from the artist’s studio do duty as subjects like those of Peter Blake, another manic collector of bits and bobs awaiting call-up and immortalisation. In Reclining Robot, a robot reclines on grass so realistic as to be show-stealer: while the robot, and in another picture a wooden doll, sleeps, the grass captivates with its layered complexity. In another, a tin crocodile and tin chicken begin from opposite ends to gobble up a runnel of corn, once more against a background on which time and effort has been lavished to the extent of diverting the viewer from the narrative’s metallo-gory outcome; ditto, a tin racing car against life size and realistic yellow lines at the side of a road. Maybe insignificance lies, too, in the discarded nature of these toys before the artist employs them as ways of understanding what it is to be human, as objects which have lost their childhood context and found other, more unsettling, ones.

Attention to minutiae is apparent elsewhere; for example, in Woodland Scene, a Klimt-like composition drawing the eye not to distances but to foreground surface interest, in this case meticulously rendered vegetation. Bearing in mind that these ambitious compositions are executed in watercolour, one might expect more broad-brushed wash than pinpoint accuracy. But, for the purposes of this exhibition at least, McCarthy is a draughtsman in paint. Even in the last of the bigger pictures, Woman With Cat, large swathes of colour limited in number contrast with the subject’s anatomical components, almost comically applied. One can imagine that the artist spent a deal of time deciding where to place the animal, eventually opting for a position that reflects both pictorial and feline independence. More than that, the picture is part of the show’s new work, a departure embracing wit and what appears to be whimsy. It’s characterised by the horizontal Tin Toy Series of paintings, in which objects from the artist’s studio do duty as subjects like those of Peter Blake, another manic collector of bits and bobs awaiting call-up and immortalisation. In Reclining Robot, a robot reclines on grass so realistic as to be show-stealer: while the robot, and in another picture a wooden doll, sleeps, the grass captivates with its layered complexity. In another, a tin crocodile and tin chicken begin from opposite ends to gobble up a runnel of corn, once more against a background on which time and effort has been lavished to the extent of diverting the viewer from the narrative’s metallo-gory outcome; ditto, a tin racing car against life size and realistic yellow lines at the side of a road. Maybe insignificance lies, too, in the discarded nature of these toys before the artist employs them as ways of understanding what it is to be human, as objects which have lost their childhood context and found other, more unsettling, ones.

For such quirkiness is capable of transformation into the grotesque, and therein may lie the significant departure of the show. That dozing robot is awakened to ‘sit’ for nine oil/acrylic monoprints on paper and in colours not applied with such lack of inhibition for some time. In disturbing torso portraits and full figure, the human lurks imprisoned behind the robotic, and in some cases has clearly become irretrievable. McCarthy has spoken of how monoprinting can result in the unexpected, in visual ‘accidents’ to be either retained or discarded, the creative process thus becoming a matter of choice. On the Kickplate’s limited wall space, he has hung an impressive array, but like other exhibitors has been obliged to choose a variety of work to reflect versatility of sometimes clashing subject-matter. In a corner is a stickman self-portrait, whittled from natural wood, painted and mounted on a black letter M. Beside it is a conventional self-portrait, the artist looking inscrutable above the word ‘Insignificant’. The picture was not meant to be for sale but it was bought at the opening view. Significant to someone, obviously.

Clive McCarthy: Recent Paintings. Kickplate Gallery, Abertillery, 4 March – 1 April 2017. All paintings for sale.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.