Living in Ystradgynlais, photographer Roger Tiley will be aware of the town’s association with the artist Josef Herman, whose life’s work was almost entirely given over to the depiction of human labour and any dignity with which it could be imbued. Herman’s most famous subject-matter was the district’s coalminers, who appear in his paintings and drawings as almost abstract personifications of endurance, with few hints of a life of motion and variety beyond home and pit. Some of the paintings are literally iconic, the bowed back and the sturdy shoulders bearing the weight of the world, or the miner’s and peasant’s experience of it. The critic John Berger took issue with Herman over the artist’s inability or unwillingness to portray the miners as militant; for his part, Herman, who lived through the miners’ strike of 1984-85 and died fifteen years later far away from the industrial valleys of South Wales, is not recorded as having heeded Berger’s misgivings. Tiley’s photographs of miners and mining, however, currently on show at the Kickplate Gallery, Abertillery, give us both the stoicism and the political engagement.

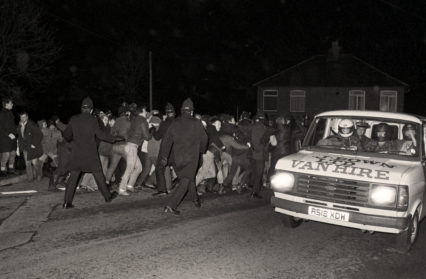

Tiley, a former pupil of Cwmcarn Secondary School, began his career in 1978 as an apprentice industrial photographer. He studied in Gwent with the Magnum photographer David Hurn and subsequently worked as a photo-journalist. Where the gallery’s preceding exhibition, How Green Was My Valley, explored Gwent’s industrial landscape of the 1980s in photographs by Ron McCormick, Tiley’s Coal Faces: Changing Places concentrates on the miners and mining communities of the same area. If McCormick’s locations were in transition, Tiley’s have gone altogether in terms of the pits where his subjects worked. The photographs of both, therefore, are not only documents but historical ones. Most of the images in Tiley’s exhibition were taken in the same decade as McCormick’s, most commonly at Celynen South Colliery, Blaenau Gwent. The subjects are personal and particular (though, curiously, not all are given names), so the figures lose some of Herman’s universal quality – in this context, no great loss. Also, where nothing about Herman’s miners is self-conscious, a few of Tiley’s are in this small selection of his work. In documentary photography, it’s better if no-one bar the photographer knows the document is being created, otherwise there’s a tacit complicity between camera and subject that works against the grain. This is true of Miners Emerging from Cage Rush to Pithead Baths, Celynen South 1982, in which the colliers are smiling at the presence of a photographer, but not of Banksman Stopping a Coal Dram or Paper Work at the End of a Shift, in which individuals are carrying out work that brooks no diversion. At the other end of this spectrum of awareness is Scabs Breaking through Picket Line, Celynen South, 1985, which records the drama, the danger, and the enmity of the strike. The use of the unpredicated ‘scabs’ perhaps indicates the photographer’s sympathy for the strikers. The ‘scabs’ wouldn’t have regarded themselves as wrongdoers as they crouch, unidentified, in the back of a hired van driven by a trio of hard-hatted honchos while, to the left, strikers and police engage in a rolling maul. It’s difficult, thirty years on, to remember how bitter were the divisions at the time. It would be different if the coalfields had survived and, more importantly, if the miners had won. Topside clashes apart, survival in the depths was always an issue, as witness two photographs taken at the Mines Rescue centre in Crumlin of men training in temperatures of 35° Celsius; they’re the epitome of individuals taking their work seriously.

Tiley, a former pupil of Cwmcarn Secondary School, began his career in 1978 as an apprentice industrial photographer. He studied in Gwent with the Magnum photographer David Hurn and subsequently worked as a photo-journalist. Where the gallery’s preceding exhibition, How Green Was My Valley, explored Gwent’s industrial landscape of the 1980s in photographs by Ron McCormick, Tiley’s Coal Faces: Changing Places concentrates on the miners and mining communities of the same area. If McCormick’s locations were in transition, Tiley’s have gone altogether in terms of the pits where his subjects worked. The photographs of both, therefore, are not only documents but historical ones. Most of the images in Tiley’s exhibition were taken in the same decade as McCormick’s, most commonly at Celynen South Colliery, Blaenau Gwent. The subjects are personal and particular (though, curiously, not all are given names), so the figures lose some of Herman’s universal quality – in this context, no great loss. Also, where nothing about Herman’s miners is self-conscious, a few of Tiley’s are in this small selection of his work. In documentary photography, it’s better if no-one bar the photographer knows the document is being created, otherwise there’s a tacit complicity between camera and subject that works against the grain. This is true of Miners Emerging from Cage Rush to Pithead Baths, Celynen South 1982, in which the colliers are smiling at the presence of a photographer, but not of Banksman Stopping a Coal Dram or Paper Work at the End of a Shift, in which individuals are carrying out work that brooks no diversion. At the other end of this spectrum of awareness is Scabs Breaking through Picket Line, Celynen South, 1985, which records the drama, the danger, and the enmity of the strike. The use of the unpredicated ‘scabs’ perhaps indicates the photographer’s sympathy for the strikers. The ‘scabs’ wouldn’t have regarded themselves as wrongdoers as they crouch, unidentified, in the back of a hired van driven by a trio of hard-hatted honchos while, to the left, strikers and police engage in a rolling maul. It’s difficult, thirty years on, to remember how bitter were the divisions at the time. It would be different if the coalfields had survived and, more importantly, if the miners had won. Topside clashes apart, survival in the depths was always an issue, as witness two photographs taken at the Mines Rescue centre in Crumlin of men training in temperatures of 35° Celsius; they’re the epitome of individuals taking their work seriously.

The Kickplate is a small gallery, and this militates against any desire by the exhibitors to include a great deal of work; by the same token, it makes them concentrate on choosing a wide and representative selection of it, even if there are only one or two examples in each category. Thus does the strike, with its unsmiling soup kitchens and support groups, take its place in this show among the many other examples of what mining and the mining community was all about. There’s an intriguing image from 2014 – the only colour photograph on display – showing an overgrown area at the site of Celynen North with an official sign stating ‘No Miners’. Apart from the post-strike, post-coalmining humour of it, the injunction presumably referred to any miners who might have thought there was coal to be had on some abandoned tip, and knew how to get at it. In these places, you couldn’t turn your back on coal and its complementary industries.

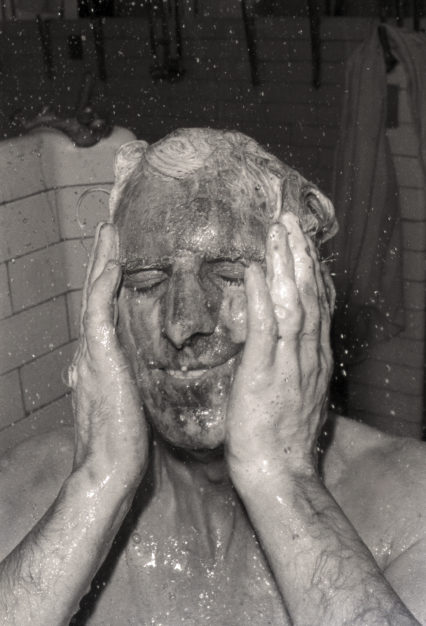

The journey taken by Miner’s Wife returning Home to West End, Abercarn, after Shopping in Village, is beside a rail track and against an industrial backdrop. The term ‘village’ also raises an ironic smile; it’s as inaccurately redolent of the countryside as is the mill in ‘Satanic mill’. Maybe that’s what the smiles are about. There are none from old Mr Coles, standing beside an example of the ‘two-up, two-down’ in which he’d lived all his life at The Ranks, Crumlin, or from the pensioner scavenging for waste material. Coal mining created a lot of waste, in several meanings of the word; it was a feature against which the virtues of companionship and pride stood counter, as in the 1982 portrait of young electrician Kieron Bartlett, and the un-named lampman photographed, with his lamps, at the same location at the same time. On hand, too, was Ivor Herbert, sluicing himself down in the shower, and caring not a hoot about the photographer’s presence. (The image of him is similar to the paintings of miners executed by another artist in the Herman tradition: Jack Crabtree.) The sun doesn’t shine on Tiley’s locations, not even on the lone elder in Sunday Morning chapel Service, Hafodyrynys, though it was probably responsible for the silhouetted drama of Pithead Winding Gear. The exhibition’s range is further exemplified in images of rescuers and their kit, and in two of a drift mine near Pontypool. The supreme irony in a show full of the conventional sort is the picture of a miner loading a dram with coal underground. It’s a classic mining image but it was taken in a private mine of the kind that for a while outlived sunken-shaft operations. The life was the same, the politics and the commerce different. The dram-tethered horse in one of the pictures looks as though it could have done with a break as much as the miner in charge of it. Those small-scale mining entrepreneurs have mostly all gone, along with the monolithic National Coal Board.

The journey taken by Miner’s Wife returning Home to West End, Abercarn, after Shopping in Village, is beside a rail track and against an industrial backdrop. The term ‘village’ also raises an ironic smile; it’s as inaccurately redolent of the countryside as is the mill in ‘Satanic mill’. Maybe that’s what the smiles are about. There are none from old Mr Coles, standing beside an example of the ‘two-up, two-down’ in which he’d lived all his life at The Ranks, Crumlin, or from the pensioner scavenging for waste material. Coal mining created a lot of waste, in several meanings of the word; it was a feature against which the virtues of companionship and pride stood counter, as in the 1982 portrait of young electrician Kieron Bartlett, and the un-named lampman photographed, with his lamps, at the same location at the same time. On hand, too, was Ivor Herbert, sluicing himself down in the shower, and caring not a hoot about the photographer’s presence. (The image of him is similar to the paintings of miners executed by another artist in the Herman tradition: Jack Crabtree.) The sun doesn’t shine on Tiley’s locations, not even on the lone elder in Sunday Morning chapel Service, Hafodyrynys, though it was probably responsible for the silhouetted drama of Pithead Winding Gear. The exhibition’s range is further exemplified in images of rescuers and their kit, and in two of a drift mine near Pontypool. The supreme irony in a show full of the conventional sort is the picture of a miner loading a dram with coal underground. It’s a classic mining image but it was taken in a private mine of the kind that for a while outlived sunken-shaft operations. The life was the same, the politics and the commerce different. The dram-tethered horse in one of the pictures looks as though it could have done with a break as much as the miner in charge of it. Those small-scale mining entrepreneurs have mostly all gone, along with the monolithic National Coal Board.

There must be photographers who could mount an exhibition about the miners’ strike alone. Maybe Tiley is one. But coal mining and the communities which depended on it were part of an often rich and variegated culture. The strike, we realise now, was its strangulated swansong. This exhibition, though restricted by space in which to give the theme full sail, at least acknowledges that culture. In taking account of the militancy and strife, it supplies something missing from Herman’s work while itself sidelining the commonplaces of palpable joy and comradeship that in mining communities especially were a means of countering hard times and hard lives. Miners were no more saintly than the rest of us, however, as stories of life underground will confirm. Artists and photographers, essentially outsiders, could not be expected to record it all, but Tiley and others show that there’s merit in the effort, even if the temptations of stereotyping are difficult to resist. At the coalface, though, everything was pretty much bleak and black; or, in the case of this sort of exhibition, black and white. Tiley, like McCormick, had a knack in those turbulent times of giving documentary records the dignity and permanence they always deserved.

There must be photographers who could mount an exhibition about the miners’ strike alone. Maybe Tiley is one. But coal mining and the communities which depended on it were part of an often rich and variegated culture. The strike, we realise now, was its strangulated swansong. This exhibition, though restricted by space in which to give the theme full sail, at least acknowledges that culture. In taking account of the militancy and strife, it supplies something missing from Herman’s work while itself sidelining the commonplaces of palpable joy and comradeship that in mining communities especially were a means of countering hard times and hard lives. Miners were no more saintly than the rest of us, however, as stories of life underground will confirm. Artists and photographers, essentially outsiders, could not be expected to record it all, but Tiley and others show that there’s merit in the effort, even if the temptations of stereotyping are difficult to resist. At the coalface, though, everything was pretty much bleak and black; or, in the case of this sort of exhibition, black and white. Tiley, like McCormick, had a knack in those turbulent times of giving documentary records the dignity and permanence they always deserved.

Coal faces: Changing Places. The Kickplate Gallery, Abertillery, until 5 November, 2016

Roger Tiley was born in 1960 and has lived in the South Wales valleys all his life. He began his professional career as an apprentice industrial photographer at Lucas Girling in Cwmbran. After studying at Newport College of Art with the Magnum photographer David Hurn, he worked on commissions for national newspapers and magazines, including the Sunday Times, the Observer, the Times, and the Guardian. His first important commission was received in 1986, when with David Bailey, Ron McCormick, John Davies and Paul Reas, he photographed mining communities following the miners’ strike. Since then, he has worked on many assignments in Britain and America. He also lectures on photography.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.