Lin Cummins reflects on the growth of 2019’s Northern Eye Festival, the annual international photography festival that takes place over two weeks in Colwyn Bay.

The Northern Eye International Photography Festival, now in its second biennial year, unashamedly takes as its focus the genre of social documentary photography. Developing and expanding on its older sibling, the Aberystwyth Eye Festival‘s traditional intensive weekend of speakers from the world of photography, Northern Eye presents the work of northern photographers in a varied programme of ‘Fringe’ exhibitions. The exhibitions populate unexpected spaces in the North Wales coastal town of Colwyn Bay for two weeks around a ‘Speakers Weekend’ in early October.

Paul Sampson, Northern Eye festival curator and founder of Oriel Colwyn, a gallery space dedicated to showcasing photography from both established and up-and-coming talent, was keen to explain that the ‘Fringe’ is an essential part of the festival, showing the work of nationally and internationally known photographers alongside newly emerging artists in a celebration of contemporary photography.

From poignant portraits of teenagers, shown in the cavernous space of the shiny new council offices, to images of female mine clearance workers in Laos, shown in a former greengrocer’s shop, the festival brings some of the best documentary portraiture, reportage and social comment, and over 5,500 visitors, to the town.

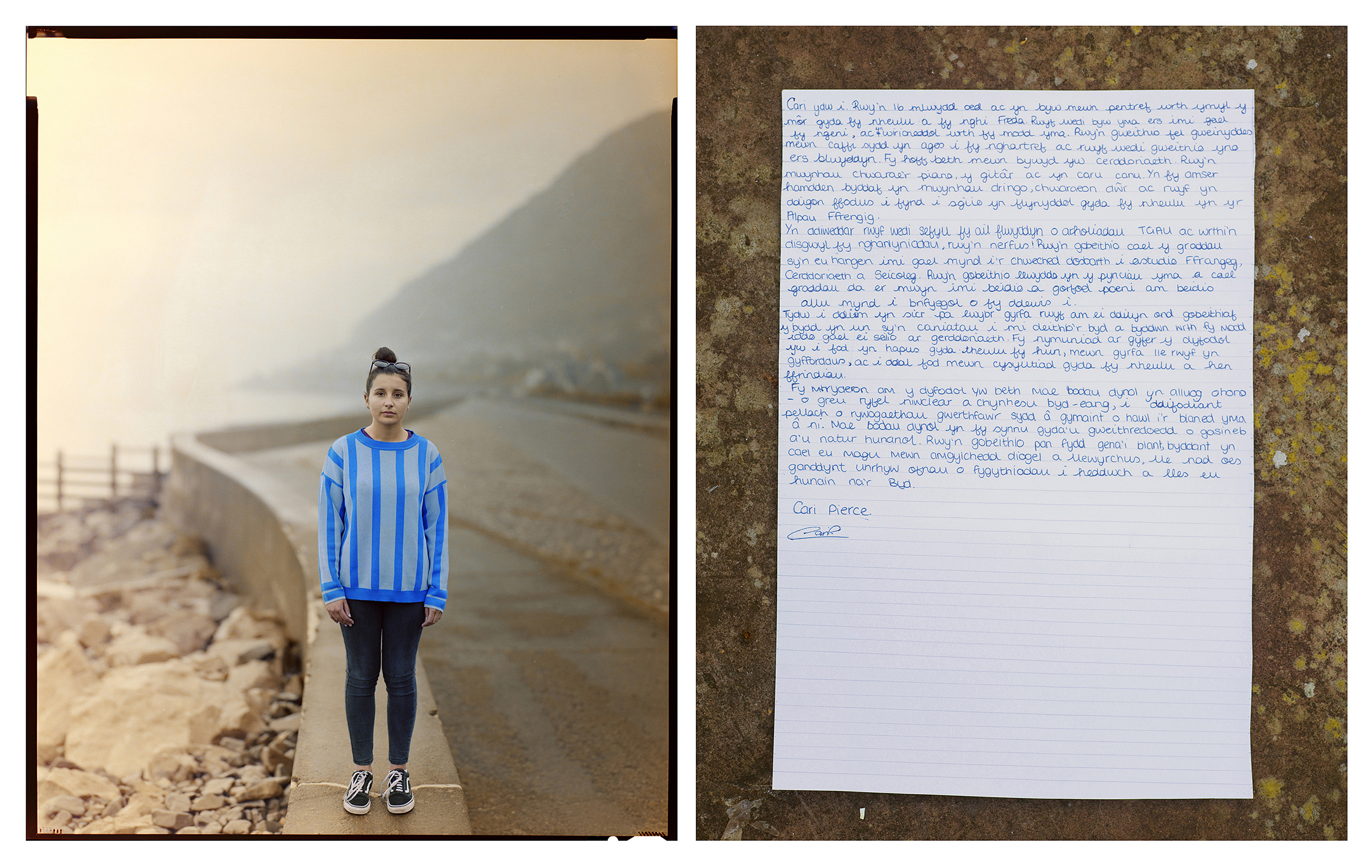

Craig Easton’s SIXTEEN was conceived in 2014, when 16 year olds were first given the vote in Scotland and, later, leading contemporary photographers joined forces with over 170 young people from across the UK to respond to the question: What’s it like to be 16 years old now?

I was struck by the range of ‘voices rarely heard’ with common concerns around hopes for the future, fears about climate change, about Brexit and about making the right or wrong decisions. The large-scale beautiful images were striking but I was most affected by the text accompanying each, evidencing a vastly varied approach to collaboration between the subject and photographer.

Scott, from Northern Ireland, photographed by David Copeland, writes a letter to his imagined future 32 year old self, questioning his hopes and dreams. “Did I succeed?” he asks. “Did I stick at my dreams? Did I believe in myself or let my friends bring me down?” He signs off with a postscript, “PS. Are you happy?”

Linda Brownlee’s monochrome expressionist portraits of Damilare and Eben are accompanied by poems written in the hand of the subjects, truly moving and, at the same time, inspirational and revealing in their insight. Others express themselves in colloquial or native language, or through transcribed interview or quote and I felt the most successful to be those that gave true voice to the photographed.

I found myself saddened by one photograph by Michelle Sank, in particular. Cameron from Cornwall, barefoot and vulnerable, appeared to have been given a short perfunctory questionnaire to complete. After going through the motions of answering the questions in an almost monosyllabic way, he goes on to write a stark and painful account of losing both of his parents, and then going on to struggle with both mental health and homelessness.

In this rather apt location, amongst the trappings of bureaucracy and council meetings in a glossy building that belies the tragedy of government cuts to council spending and its decimation of youth provision, the power of these images and texts set me to thinking about the power relationship between the artist and the subject, and the almost impossible task of photography’s claim to always pursue a truthful integrity.

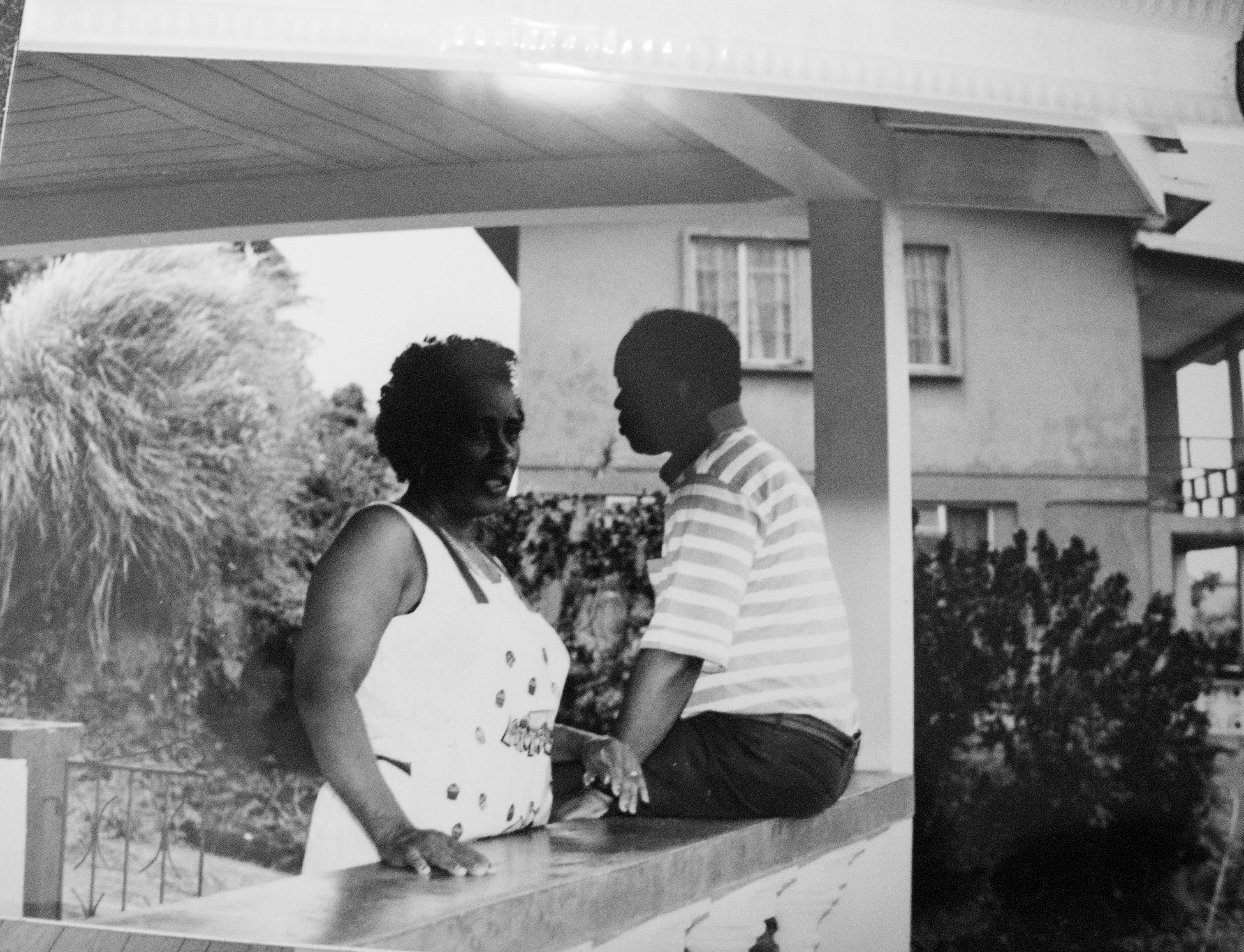

Sandra Harper’s deeply personal and moving account of her mother’s devotion and care for her father during the last years of his life, Hestelle – on show in the foyer of the nearby library – could not better illustrate the importance of a relationship of trust between those behind and those in front of the camera. Beautifully observed and revealing, the photographs were hung in groups that depicted, in turn, the early days of Hestelle and her husband Alexander; the strain and exhaustion of a full-time carer; the daily routine, the small details, the meds, the TV guide, the books, and the finality of the crumpled sheets of an empty bed. The photographs express an intimacy that probably only a very close relationship can accomplish and that possibly no commissioned photographer could ever hope to achieve.

Niall McDiarmid’s State of Independents – photographs of independent traders and shopkeepers from the town and nearby Rhos-on-Sea, shown in promenade shelters along the seafront, in contrast, are documents in the most elementary sense of the word. The subjects look passively back at the viewer and give very little away about who, or how, they truly are. I wanted to know more and wondered how much agency they had in how they were photographed or portrayed. It will be interesting to see how the hopes for the project to become a catalyst for deeper engagement between photographer, business and community will evolve in the future.

Photographer Dan Wood, whose work Gap in the Hedge is shown in the gallery space at Theatr Colwyn, was born, and still lives, in the area that he documents. His softly saturated colour images of bikers, grumpy princesses, yogis and military men, and their relationships to the landscape of the Welsh valleys, are left uncaptioned. The photographs are hung in pairs, alternately full of presence, with the subject commanding centre frame, or completely devoid of presence. In this way, Paul Sampson, who both curated and hung the exhibition, has created new or implied meanings and demonstrates a total trust between artist and curator which really worked.

I was disappointed that this year there was no exhibition in the former Betterbuys wallpaper shop which, in 2017, had been a perfect venue for an exhibition of photographs of people dis-counted from society, set against a disintegrating backdrop of discontinued sale items. Instead I found, in the old Arundales greengrocers shop on the town’s former bustling, and now somewhat bedraggled, main shopping street, Brian David Stevens’ Doggerland – a vinyl wallpaper image-overload of beautiful, and mildly disturbing, evocative black and white images juxtaposing icons of popular culture, social deprivation and religious references. I wondered whether it was a conscious curatorial decision to place Stevens’ work in this way, in this place – now a community outreach meeting place owned by a local church group – or whether my reading of the work was coloured by my conversations with the people from the church group. Paul told me that the the work was hung as a vinyl wallpaper for both practical and aesthetic reasons. It seemed apt for the images to be presented in the same way that we make and consume images today, immediately and almost voraciously. Referencing the ‘Doggerland’ of the exhibition title – an area of land that connected Britain to Europe until it was flooded by rising sea levels over 8,000 years ago – the images reflect upon and are submerged beneath layers of shifting perspective and meaning.

Doggerland © Brian David Stevens

Doggerland © Brian David Stevens

At the same venue was Tessa Bunney’s The Women of UCT6 which shows alternately serious and joyful images of the women of an all-female UXO (Unexploded Ordnance) clearance team working for the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) in Laos. The U.S. army dropped more than two million tons of ordnance in the country during the Vietnam War and more than 50,000 people have been killed and injured as a result since 1964. The church group now running this space are based at Capel Salem in Colwyn Bay. With ‘Salem’ the Hebrew word for ‘complete or perfect peace’, I once again found the choice of venue added richer meaning to the work.

Upstairs, in the same premises, Dave Thomas’s Treasures in Syria – which documents archaeological sites being systematically looted or destroyed by bulldozers or by ISIS – was set in a room with a chimney breast plastered with pages from English and Welsh language bibles. Paul Sampson told me that this was how the room was found and it was decided that it would remain this way, again adding layers of interpretation to Thomas’s beautifully executed images of disappearing worlds amongst combat zones.

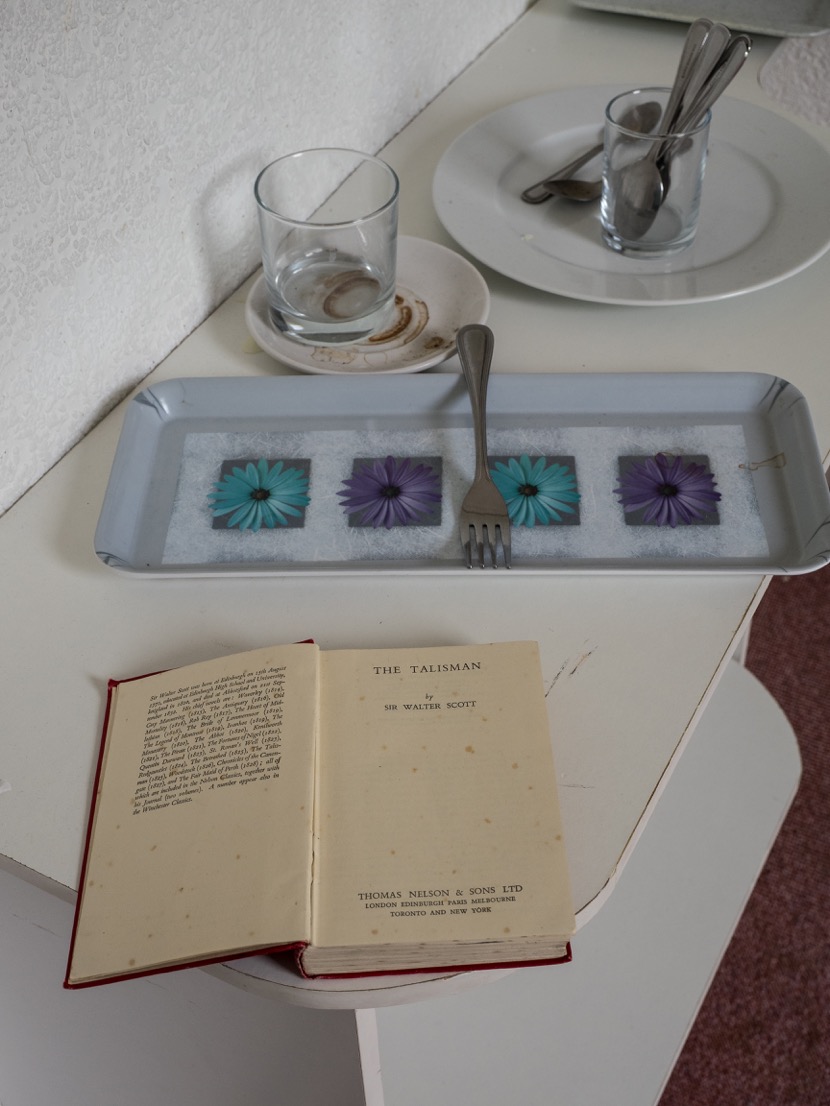

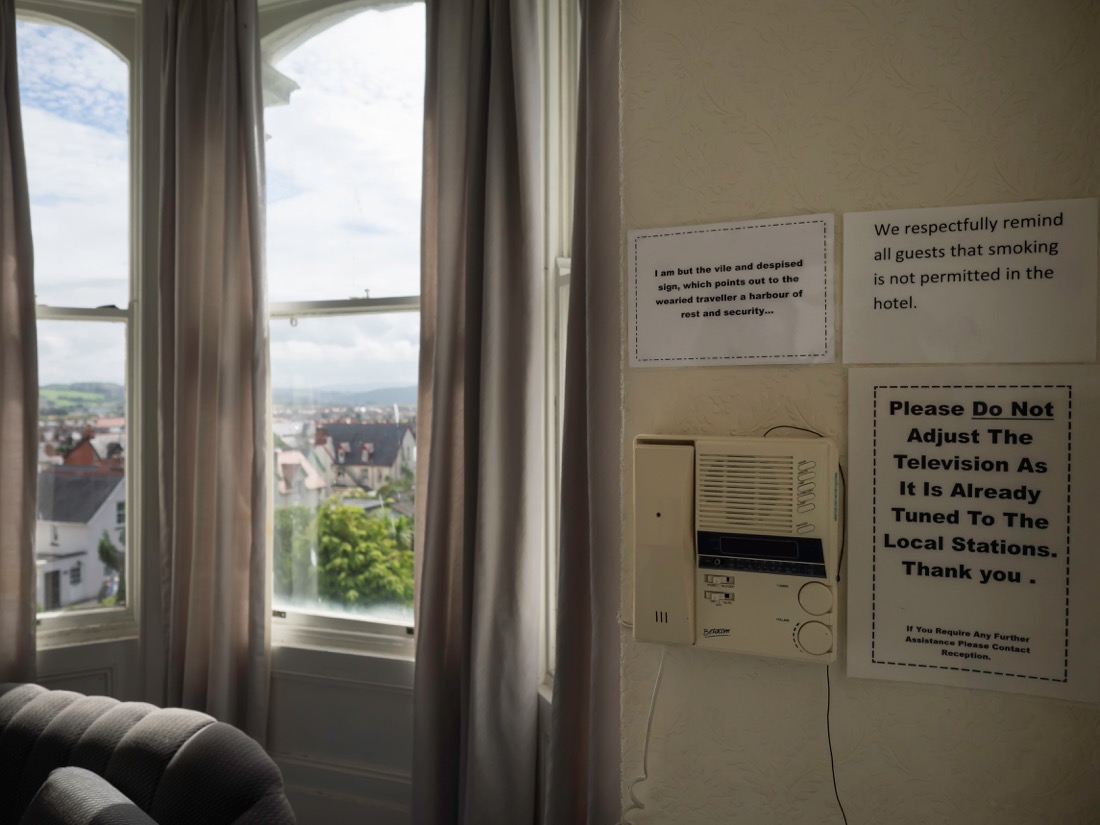

And next door, in a tiny room overlooking the roofs of the town, Antonia Dewhurst’s The Talisman inhabited a tableau of domesticity, with TV monitor, armchair, reading lamp and a copy of a book of the same name by Sir Walter Scott. Dewhurst had come across the book, left in a room by one of the transitory residents of the squatted former Royal Hotel in nearby Llandudno, while on a photographic exploration of the building. On reading, she found that the book’s setting against the background of war in the Middle East gave the subject matter a narrative thread, and her work couples quotes from the original text with mundane hotel management signs, and more poignant absences of presence, in the recently abandoned hotel rooms. Dewhurst’s artistic practice is around ‘home’ – what it is and what is means to find home. Quotes selected from the book were deliberately chosen to resonate with the idea of homelessness and the plight of the people who had passed through the hotel looking for shelter and a home, particularly those who might have been escaping war and looking for asylum. I chatted briefly with Antonia Dewhurst, who told me that it feels to her like a generosity to the viewer of her work to give them some work to do in finding the “rhymes between things”, a kind of poetic rhythm that happens as a body of work develops and finds its context. Antonia played a considerable role in making Northern Eye happen, working closely with Paul Sampson on hanging many of the exhibitions and being entrusted to make curatorial decisions on a significant few. As with many of the seemingly incongruous settings of Northern Eye, both the exhibition’s location and how the work is presented brought a much deeper understanding of the artist’s response to subject.

The Talisman © Antonia Dewhurst

The Talisman © Antonia Dewhurst

The Talisman © Antonia Dewhurst

The Talisman © Antonia Dewhurst

At the core of the festival is the ‘Speakers Weekend’ of which, unfortunately, I only managed to catch a small part, on Sunday afternoon.

Olivia Arthur – who for Jeddah Diary found herself in a position of trust and intimacy in photographing young women behind the burqa and explored the boundaries and various hues of privacy, intimacy, and identity in Mumbai whilst making her In Private body of work – talked of using the 5×4 format camera which she described as giving an “honest import to the work”. Conversely, Brian David Stevens talked of reverting to using only a standard fixed lens in a desire for there to be as little a thing between him and what he sees. Seasoned photojournalist John Bulmer responded to the question “How important is the text to the photograph?” by saying that a photographer simply takes the picture and hopes that people find it interesting and that a good picture is one that “solely catches you in the gut”. His assertion that no caption should be required seemed to cling to the notion that the photographer’s truth is ‘the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth’. A number of the photographers spoke of “making”, rather than “taking”, a photograph while Tessa Bunney, interestingly I thought, referred to her subjects as “protagonists”, which seemed to signal a self-awareness around the subject/photographer dynamic.

The different approaches of the speakers confirmed that, coursing through the veins of any photographic documentary maker is a striving for a raw and objective truth. At the same time, and further to the long discussed power relationship between photographer and subject, the range of work and presentations throughout the festival made me consider the shift and flow between the actual truth, the perceived truth, the photographer’s ‘truth’ implicit in an image and the realities created when a work is captioned or left un-captioned or when a body of work is edited or hung in a space.

I was sorry to miss Joanne Coates, whose talk several people told me they were both moved and inspired by, and a photographer whose approach to photography is ‘democratic and poetic’. Founder of Yorkshire-based creative community ‘Lens Think’ which aims to fight for class equality in the creative industries, Jo has described photography as “not the most diverse medium in terms of who does the photo taking”, something that, in established ‘serious’ documentary photography circles at least, doesn’t seem to have changed.

What is most exciting about the Northern Eye Festival is the way in which considered, curatorial decisions and unexpected meetings of image and context spark conversations around about what it means to document the world we live in today and the festival brings that conversation right into the heart of this seaside town that’s seen better times.

In a world overflowing with throwaway images like so much plastic in the ocean, in a climate of fake news, fake filters and digital manipulation, and with questions around the ownership and use of our personal photographs hot topics for debate, it seems that now, more than ever, we should be placing the means of production in the hands of the subject. Alongside the main events over the festival period, Paul told me that there had been workshops around the town, fanzine swaps, a ‘PechaKucha’ style event (a storytelling format, where a presenter shows 20 slides for 20 seconds of commentary) and a real sense of community among seasoned and new photographers, and festival visitors alike.

I’m looking forward to seeing how Northern Eye, currently at the forefront of a cultural regeneration of the town of Colwyn Bay, will continue to show the best in contemporary photography; in cafés, in music shops, in railway stations and shopping centres, and inspire new communities and generations of ‘truth-tellers’ over the coming years.