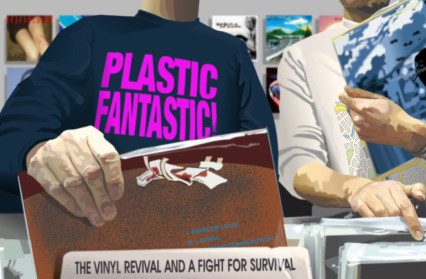

Craig Austin discusses the ‘vinyl revival’ and how and why we should support local, independent record shops in Wales with Diverse Music and Paul Hawkins.

‘Over The Border’, the first song on Saint Etienne’s most recent album, Words and Music by Saint Etienne is one of the most remarkable songs of the last year. Its opening line, ‘When I was 10 I wanted to travel the world’, invites the listener into the development of a deeply personal and life-long love affair with the visceral joy and infinite possibility of pop music, its trappings and its artefacts; an unashamed fetishisation of ‘green and yellow Harvests, pink Pyes, silver Bells, and the strange and important sound of the synthesiser’, a world of ‘first kisses and terrible chat-up lines’ but where, in the end, ‘the conversation always turned to music’. As a love letter to the object of its desire it is both wholly celebratory and unreservedly peerless. On the day of the album’s release I cycled to my local record shop to buy a copy on vinyl, much as I would have done as a 12 year-old kid, only then it would have been a journey undertaken by BMX to the hallowed post-punk, pre-CD, Pandora’s box of thrills that was (the now long-since defunct) Tracks Records in Cwmbran; a beacon of hope and escapism in a brutalist concrete South Wales new-town more reminiscent of cold war Belgrade than downtown Manhattan. In common with so many of my peer group, I too wanted ‘to travel the world’ and in the absence of either income or opportunity, Tracks, with its aromatic racks of glossy cardboard and shiny black plastic offered up the alluring twin prospects of glamour and escapism and acted as my de facto travel agent of choice. Accordingly, I lived my life and measured my aspirations not by the narrow and limited world-view presented to me by my schoolteachers and 80s society at large but via the glittering diamanté prism offered up by Adam Ant, Siouxsie Sioux and Billy MacKenzie. Tracks became the epicentre of my tiny world for a deliriously giddy period of three of four years, one that fortuitously coincided with the creation of some of the most inventive, ground-breaking and utterly thrilling pop music that this country has ever produced. My previously suffocating teenage existence became an infinitely better place to be as a consequence and ‘it all happened’, to quote Saint Etienne, ‘because of music’.

Though Tracks’ owner, John Richards, finally closed its doors not long after the advent of CD, the notion of the record shop as both provider and shaper of the nation’s musical needs did not die with it. Partly driven by the major labels’ attempts to promote the CD as the shiny pristine format of a glittering technological future (often via the calculatingly incremental reduction in both the quality and thickness of the vinyl they begrudgingly continued to press), and partly by the nation’s seemingly unquenchable thirst for musical product, independent record shops and the high street monoliths of HMV, Virgin and Tower continued to co-exist in a spirit of – if not total harmony – at least, amicable tolerance. CDs were selling in vast quantities across the entire sector, and at prices that with hindsight were truly eye-watering (especially to the minds of today’s music consumers, many of whom resent the prospect of paying anything towards the sound-tracking of their lives). Tellingly, it didn’t take too long for Tracks to experience a cultural rebirth that says much about the commercial resilience of music retail in the late 80s, rising phoenix-like from the embers of its previous incarnation to assert itself amongst the long-established record shops of Newport under its new moniker, Diverse Music, in late 1988. Emboldened by the emergence of a thriving dance music scene and a long-standing alt-rock community that had its roots in the hard-core Minneapolis scene of Husker Du and The Replacements and which would one day lead to Newport being described as ‘the new Seattle’, Diverse counted amongst its loyal customer base one Paul Hawkins, bequiffed teenage Pixies obsessive, and the man to whom the keys to the palace of wonder (and its resultant headaches) would one day be handed over. The passing on of a still-thriving pop cultural baton from one generation to another that took place in complete ignorance of the oncoming storm that was steadily preparing to besiege the high street record shops of Newport, Cardiff, London and Manhattan.

‘Coffee’, says Hawkins, the word underlined at the top of a sheaf of handwritten notes that he brandishes at me across a pub table. ‘That’s how record shops, the likes of Rough Trade, certainly the massive one in East London, make money these days; by diversification, by reinventing themselves’. When Paul and I first spoke about the notion of a ‘vinyl revival’ – an undeniable and ever-growing phenomenon – and what many have consequently viewed as the improbable renaissance of the record shop he openly bristled at the notion of such received wisdom and the almost celebratory contemporary articles and features that have prevailed in its wake. We meet in the same week that the once all-conquering HMV finally stumbled into administration, putting 4000 jobs at risk, and bringing with it an ironic outpouring of 11th hour revisionist nostalgia for a chain of shops that many of these part-time mourners won’t have stepped inside for over a decade. On this, Hawkins is single-mindedly unromantic. ‘There’s been a lot of dewy-eyed reminiscing about the supposed death of HMV and the so-called ‘good old days’ at a time when there are still 200 or so shops out there still doing exactly what these people are getting so dewy-eyed about. They’ve not got any idea that these shops even exist which is even more galling when you consider that if these people hadn’t played such a part in their demise they wouldn’t need to be sat around reminiscing’.

Hawkins’ understandable frustration about this self-perpetuating spiral is clearly accentuated by recent press coverage that has sought to make the case that all is currently rosy in the garden of independent music retail, a belief no doubt strengthened by sales of vinyl albums having steadily increased over the last five years with the value of the market increasing from £3.4m million in 2011 to £5.7 million in 2012; an eye-catching headline and proof of an ever-increasing demand for tangible physical product but still a relatively tiny proportion of total music sales within the UK’s download-dominated market. ‘There’ve been plenty of articles about the vinyl revival but only Graham Jones’ book, The Last Shop Standing, has dealt with the realities of survival for shops like ours. People are very vocal about how supposedly sad it all is but they do nothing to stop it happening. It’s not unlike when those same kind of people make a point of going out to buy a copy of a Dave Brubeck record because he recently died despite not bothering to celebrate him when he was alive’. Hawkins smiles, as if the metaphor works perfectly for his own experience of trying to keep his own record shop afloat under the most trying of circumstances: ‘It’s a really good promotional tool, dying; you’re back in the game when you’re not supposed to be’.

At a time when vinyl may well have finally won its interminable format battle with the now moribund and (ironically for those of us who remember its initial unveiling on TV programmes like ‘Tomorrow’s World’) archaic and ultimately disposable CD, it’s the latter-day war between the physical and digital formats that has truly brought so many of our treasured shops to their knees; a conflict played out in the shadow of the internet and with retailers who would laugh at the notion of a high street presence being in any way important. It may therefore come as something of a surprise to hear the owner of a fiercely independent record shop voicing his belief that the latter-day vinyl revival has actually been driven by the internet. ‘My take on the internet is exactly the same as Homer Simpson’s take on alcohol,’ Hawkins grins. ‘It’s the cause of, and solution to, all of life’s problems’. He elaborates: ‘When the internet began to creep into people’s homes it gave everyone instant access to this massive database of products and information and its solely because of that that some guy in Japan now knows I’ve got the new Paul Weller album on vinyl and hey, I’ve got a worldwide market as a result. What it initially took away from us in CD sales it also allowed us to offer our business to the world’. It’s an outlet that has created opportunity for Diverse Music, and its vinyl-only independent record label, Diverse Records, but it’s one that ironically played a huge role in the ultimate demise of HMV whose separate offshore online business sucked the life out of what was left of its increasingly ailing core operation. ‘What kind of business model drives traffic to a company that is entirely independent from them? People are creatures of habit so when you change their buying habits you very rarely change them back. It was madness’.

HMV’s timeless icon, Nipper the dog, was not just a figment of a 19th century ad-man’s fertile imagination. The gramophone-gazing canine actually existed and was ultimately laid to rest only yards from a narrow thoroughfare that has since been renamed ‘Nipper Alley’ on the outskirts of Kingston-Upon-Thames’ busy shopping centre. Whilst neither the iconic dog nor its parent company has shown any sign of early resurrection its friendly neighbourhood independent record shop, Banquet Records, continues to operate on a multi-platform offering of physical product, live shows, club nights and in-store performances. It’s my local record shop, the same one I cycled to in order to buy the latest Saint Etienne record, and the beating autonomous heart of an otherwise soulless shopping district. Despite commanding a relatively small floor-space the 40 year-old shop prides itself in being ‘more than just your local record store’ and hosts a weekly indie night, along with numerous hip hop/dance shows and relatively big name in-stores (the likes of The Cribs, The Vaccines and Frank Turner) totalling around 250 events throughout the course of an average year. Much like Diverse however, the significant majority of the shop’s total sales are driven by online transactions, an unavoidable reality that doesn’t in any way detract from the vital importance of a visible high street presence. Paul Hawkins is strongly of the view that people trust websites that have physical shops: ‘They know that at the end of that line there’s a shop full of enthusiasm and enthusiastic people. People they can actually engage with’. It’s a view echoed by Banquet’s Mike Smith: ‘Like Diverse, we tailor our knowledge and stock to our core customer base and the people who live in the community. All of the shops are fighting their different battles to survive, and depending on where you are in the country the battles are very different. Whilst Diverse has honed in on the audiophile community, we’ve really focused on the audience we have on our own doorstep; what is essentially a busy, young, student town’. Mike sees his own shop and others like it as a vital part of that community and something to be treasured. ‘Over a period of time, record shops have become old institutions that are really quite precious and represent more than just a bricks and mortar store. For many, they still act as little community hubs, a ‘hang out’ and a place for people to meet for people who share a passion and a love for music and for records’. Despite the shop’s inventiveness, its diversification, and the steady flow of potential young customers provided by the town’s popular university, Mike and business partner Jon Tolley face the same financial challenges as their South Wales comrades. ‘It’s not easy at all. What’s kept us going is doing everything; the in-stores, the online business, etc. The shop might struggle to survive if we gave up doing the shows and in-stores. They offer fans of these bands the opportunity to meet their heroes up close and personal, it breaks down the barriers a bit, and for many it’s maybe the first time they’ve ever bought a physical product. It’s tough out there but at least the decisions we make are our own, they don’t need to come from some faceless head office miles away. It’s the guys on the frontline making the calls. We change our ideas and our directions almost on a daily basis. Me and Jon took on the shop when we were 23 or 24 thinking, “Yeah, we can make a record store work”, and those first few years were a pretty steep learning curve. We’re better businessmen now but we’re still constantly adapting. We have to, to survive’.

In the same week that Banquet garnered a huge amount of publicity by offering a 50% in-store discount to the seemingly luckless holders of HMV gift-cards, Mike sees little commercial payback for his own business in the demise of the corporate behemoth. ‘It’s hard to know what’s going to happen but it’s not necessarily good for us. It’s not a straight transferable customer base – though we have inherited their shoplifters! – and whilst we offered up the discount as a genuine goodwill gesture I can’t pretend there wasn’t some kind of business strategy behind it. For many who took up the offer it was their first time in any kind of independent record shop, let alone ours. If HMV goes down a lot of the labels are going to wonder whether it’s worth still producing physical product and that would impact shops like ours massively. If they don’t have a large network of shops some of them might just think well why should we bother? Another concern for us is that in some of our bigger musical towns and cities; the likes of Bristol, Manchester, and London, the opportunity might arise for some large, trendy, vinyl/CD emporium chain to step in and ultimately risk driving out some of the better indies. That would be a real problem for us and it would be hard to compete with someone who’s suddenly buying in vinyl in mass quantities’.

For both shops the double-edged commercial sword that is international Record Store Day and its attendant swathe of limited edition vinyl product available only by stepping foot into your local record shop has become a truly revelatory phenomenon. Both Paul and Mike speak openly about taking the equivalent of a month’s takings in a single day, and the excitement that it generates within the space of 24 hours is undeniable. At Diverse, Paul Hawkins’ experience is of people queuing up outside for hours. ‘It’s by far the busiest day of the year and the enthusiasm, buzz, and excitement it generates is fantastic. It’s great fun and I love it but it’s based on four years of multi-million pound PR that gets people in this shop for only one day a year. It favours the eBay chancers and can often disenfranchise our most loyal and repeat customers’. Mike and Jon’s experience of an annual day of commercial mayhem in Kingston is much same, though the shop’s evidence of repeat custom as a consequence of Record Store Day demonstrates that the aims of RSD are being quietly achieved, if not to the degree that might have initially been envisaged: ‘The last three years have been absolutely crazy, we do an entire December’s sale in one day. It’s completely changed the Banquet calendar to the extent that our Christmas now comes in April. eBay is a problem and shops need to be wise to it, and whilst we don’t issue multiple copies to anyone of what is strictly limited product it didn’t stop a middle-aged man sending in his 3-year old boy with a 5 pound note to try and buy an extra copy of the Blur single a couple of years ago!’

What is plainly evident is that you don’t get into the business of record retail in the 21st century if you’re looking to make a quick buck. It’s a labour of love in the extreme and a precarious financial balancing act for all concerned. Paul Hawkins is brutally honest about what it takes to maintain Diverse as a viable commercial operation and the personal impact upon him as a consequence. ‘I earn nowhere near the minimum wage and as much as I’d like to own my own home, I’m married to the business. You’re not in a job like this for a career or to climb through a hierarchy, you’re there for the love of music. When I meet people, when they find out what I do for a living, and when they tell me how they’d love to be doing what I do, I feel like challenging them to spend a day or so in my shoes and see if they can afford it. It’s a total lifestyle choice and it’s not easy’. Despite these harsh realities what Mike, Jon and Paul do share, however, is the freedom and self-determination to shape and focus their businesses in a way that would make the average 9 to 5 wage-slave crippled with envy, not least because they’re doing so in an environment that is more pure, and ultimately reflective of their teenage bedrooms, than it is of either the joyless corporate boardroom or the soul-destroying factory floor. On this, Paul Hawkins is categorically unswerving: ‘Being my own boss is worth a fortune to me. I run my business on my own terms, I do it at my own pace, and I’m constantly surrounded by the things that I love. I’ve got no one to answer to and whilst it’s a freedom that comes with its own set of pressures and responsibilities, it’s a freedom nonetheless’.

These aren’t just mere shop owners, these are lovers, curators and vendors of art; the keepers of the flame and some of the very few – perhaps only – true high street purveyors of hopes, dreams and teenage kicks we have left. Often surviving on tiny margins and, for some, on a month-by-month basis, yet continuing to exist on a foundation of perpetual reinvention and sheer enthusiasm in its purest form. They don’t want your sympathy, your nostalgia or your dewy-eyed reminisces. They simply want your attention, your patronage and your custom. It isn’t really too much to ask, is it? After all, and to use the rock’n’roll vernacular, you can’t put your arms around a memory. Or perhaps more pertinently, there’s no point in shouting out ‘Who killed the Kennedys?’ when after all it was you and me.

Banner illustration (vinyl record shop) by Dean Lewis

Craig Austin is a Wales Arts Review senior editor.