Phil Morris reviews Playing Burton, a film adaptation of the extraordinary life and career of Richard Burton, one of Wales’ most highly accredited actors.

The extraordinary life-story of Richard Burton is often outlined, even by those who knew him, as a myth in three parts. First, there is Richard Jenkins the boy-genius son of a Welsh miner dreaming only of playing rugby for Wales until his mentor Philip Burton, and the actor-writer-director Emlyn Williams, help to fashion his precocious acting talent. Then, there is the rechristened Richard Burton who, with a combination of incredible luck and an astounding facility with verse-speaking, entered Oxford University, stormed the English Stage and ‘made it’ in Hollywood in three improbably quick leaps. Finally, there is Burton the modern-day Faust, a movie-star who frittered away his prodigious gift under a miasma of alcohol, fame, trashy movies and Elizabeth Taylor’s tits. That, so it goes, is the legend printed by English journalists and hack-biographers, and retold by countless talking heads in television documentaries. There is nothing so mythically Welsh as a lost cause, a doomed Prince and a transient bright spark of genius.

Adapted for the screen, produced and directed by Wyndham Price

Based on the stage play by Mark Jenkins

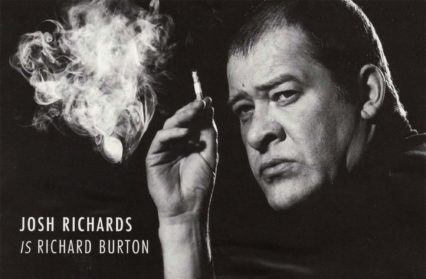

Josh Richards as Richard Burton

The signal achievement of Playing Burton – originally a one-man stage show written by playwright Mark Jenkins (not related to Burton) and adapted for television by producer-director Wyndham Price – is that the Burton myth is successfully re-imagined. The film’s intriguing conceit is to regard Richard Burton not as a renowned actor, but as a heroic leading role offered to a teenage Richard Jenkins, who then took up the part and played it, for the rest of his life, to the hilt. The gap between actor and action, between reality and representation, becomes the dilemma of Burton’s life, as it was for Hamlet, whom he played on Broadway for a record one-hundred and thirty-six performances.

The role of ‘Richard Burton’ was not self-created but produced in collaboration with Philip Burton, a local schoolteacher who occasionally wrote plays for BBC Radio. The first language of young Richard Jenkins was Welsh, but on reading a collection of English poetry he fell in love with, ‘the strength and beauty of this foreign tongue.’ The young lad was drilled by his mentor ‘every evening until ten, eleven, twelve o’clock at night’ in the rhythmical metrics of verse and the practice of elocution and vocal projection. Burton later referred to his mentor’s parlour as ‘the room of terror’. The script is acutely perceptive in its exploration of the metamorphosis that the young Jenkins underwent under the guidance of his mentor, who taught him how to eat ‘soup without sound effects’ and dress appropriately for occasions, ‘but most of all, Phillip Burton taught me to use English like a sword.’

The film is at its most penetrating in its analysis of the creation of the Burton voice, which it presents as motivated by what could be characterised as a post-colonial desire to take revenge upon the English ‘master race’ via the co-opting of their own language. The mission of both Burtons was for Richard to one day ‘teach the English how to speak their lovely language.’ Not a ‘mincing, Oxford, nanny-goat English’ but a language in which poetry resonated with passion, conviction and magisterial authority. Burton would play English kings as no Englishman could, or did; and he often talked about performing Shakespeare’s Lear in the guise of Llyr, the ancient Welsh King.

The script of Playing Burton is written, like the stage version, in blank verse, interlaced with numerous quotes from Burton’s interviews and chunks of Dr Faustus and Shakespearean drama. Rather than seem self-consciously arty and literary, this combination of original writing with classical texts confers on Burton, in his struggles against sin and self-destruction, a sense of tragic grandeur. As he grapples with the mystery of his essential self, along with multiple divorces and family tragedies, Burton seems compelled to appropriate the words of others, written in a foreign tongue, to express the deep pain that had come to lodge permanently within his soul. Quotations from Marlowe and Wilde also convey the erudition of a man who spent the entire 1977 Academy Awards ceremony – he was nominated for his role in Equus – conjugating irregular Spanish verbs in a little black notebook.

The absurdities of Burton’s immense fame: the easy money for bad films, the huge entourage that flocked around ‘the Taylors’ following, ‘the most public adultery in the history of the world’ and the constant press intrusions into his private life are given their due acknowledgement. Yet the film portrays Burton’s slow dissipation not as an inevitable consequence of his alcoholism and womanising, but rather as the result of a fruitless and hopeless never-ending search for some explanation behind his amazing good luck, and to discover if any part of Richard Jenkins had survived the excesses of his alter-ego. For Mark Jenkins, the Faustian pact that Burton struck was not with Liz Taylor and Hollywood, but with Philip Burton in the creation of a new self that would take him away from Wales into the spotlight of public expectation and global celebrity.

Wyndham Price’s film feels rather constrained by its very low budget, and inevitably long sections of it feel stagey and lack visual flair. The value of the film, however, is that it captures an outstanding performance by Josh Richards, who, like Anthony Hopkins in Oliver Stone’s Nixon, performs the neat trick of being convincing as Burton, when in fact he neither looks nor sounds very much like him. Richards’ does not impersonate Burton, but embodies the role with appropriate notes of desiccated charisma and simmering resentment.

The finest moment of Josh Richards’ performance, and indeed of Mark Jenkins’ writing, is at the moment when a deceased Burton reviews the notices of his life and career from beyond the grave. As he tears though a stream of obituaries that bemoan his wasted potential and artistic failure Burton seethes:

The English critics can forgive you for flouting tradition…but to make a million as the Prince of Denmark – a million – well that’s just not cricket, old chap. Far more edifying to play Hamlet in tights, in London, and submit yourself to ritual thrashings by The Times, the tax man and the master race.

The designation of failed promise, which has hung about Burton’s career for nearly thirty years, is the confection of mainly English theatre critics who clearly never forgave him for publicly revelling in his wealth and fame, and for not playing their game. These critics conveniently forgot that Paul Schofield once played the lead in Exclusive, a play by Jeffery Archer, that Olivier was in Clash of the Titans and that Ralph Richardson appeared in rubbish like Dragonslayer. Surely no British actor appeared in so many bad films as Burton, but who else appeared in as many good ones? These good films include: Bitter Victory, Look Back in Anger, The Night of the Iguana, Beckett, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Equus and 1984.

There is now a crop of Welsh actors, most notably Mathew Rhys and Michael Sheen, who have emerged from Burton’s shadow, in that they are able to traverse the worlds of high and low culture without the same level of criticism. Sheen followed his epic Passion of Port Talbot (in collaboration with National Theatre Wales) with appearances in the Twilight movies without facing the charge that he had sold out his talent to Hollywood.

Mark Jenkins’ Playing Burton serves to rehabilitate Burton’s reputation, to some extent, by framing his career within the epic narrative that was his life. Burton was the greatest role Richard Jenkins ever played. Although the film has its limitations, the original play is one of the most compelling and well-rounded portraits of talent written in the last thirty years.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis

Phil Morris has contributed regularly to Wales Arts Review.