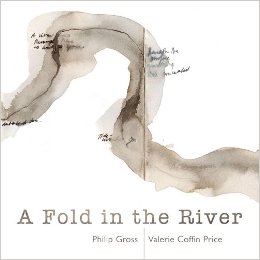

Seren, £12.99

As a hugely distinguished poet on the literary scene in Wales, Phiip Gross hardly needs introduction. Many of his readers will be familiar with his powerful evocation of the River Severn in The Water Table – the collection that won the T.S.Eliot prize in 2009. In A Fold in the River he again writes about a body of water, the Taff, but this time in collaboration with the artist Valerie Coffin Price – the latest in a series of collaborations by Gross with artists in other media. Price, herself a significant practitioner, makes clear in her artist statement* her affinity for such a project. An artist-letterer, she notes how a sense of place is fundamental to her work, while a driving force is ‘…The poetic resonance of language and its connection to the environment….’

A Fold in the River arose from Gross’s fascination for the Taff, running, as it does, close to his home. He kept journals of bank-side walks that evolved into the pieces found in this collection. According to the jacket blurb ‘Gross and Price began a a conversation at the water’s edge, between word and paint, about the river, nature, landscape, history, and ways of seeing.’ Unsurprisingly, the resultant book, is, in itself, a compelling aesthetic object, both in feel and presentation. Price’s art work and Gross’s poems are combined in riverine and arresting ways that immediately hook the reader. You travel the Taff with both artist and poet, as they bear witness to its many manifestations and the residue of its history. Gross makes an engaging guide in a series of poems that flow from surface to depths and back, linking the origins of the river, its industrial past and its elemental properties. His tone typically intimate, conversational, balancing a philosopher’s finesse with wit and precise observation that always delivers its ancient topic in a memorably fresh light. Price’s graphics create a sense of linear propulsion, as if you are in a boat, passing through one experience of the river to the next in a shifting equation of light, mood, memory, and cultural trace.

The river, however, is not to be trusted. From the start Gross reminds us of its capacity to dissolve boundaries. It spreads, invades, seeming to call forth a reciprocal ‘desire’ in solid matter to dissolve into water. In ‘The Stain ‘…..ink/ lets go – / as if the paper wants this physically. ‘ Price captures this theme in her stain-like map drawing of the river that threads through the book, with snatches of the poems positioned like locations. Gross uses personification throughout – the Taff is like a wayward trickster-divinity, full of ‘ Mad / bad pranks, extreme japes… (What to do with it)’. A familiar Gross device, it is a method of parleying with the otherness of the natural environment, both physical and metaphysical. We understand by seeing a mirror of ourselves. This is not a strategy, however, to explore the poet’s own emotions, but rather to get closer to the essential qualities of the river. But Gross is always aware of the paradoxical inseparability of the looker and the looked upon. In ‘The Long Game’ we are ‘reflection / who reflect / on all that throws them.’ And the river carries and absorbs traces of human culture. It will always, however, escape and transcend our boundaries of description. ‘Knowing the River’ asserts the Taff as ‘…a species / of knowing. Not one we can have or hold.’ In poems that explore what defines riverness, and that link it to the elements of fire and air, human consciousness is only part of the picture, even if the human load on the river is a heavy one, as here, in ‘A River Runs Through’:

poor put-upon thing, it was trying to wash

itself clean, its tired towns, bringing nearly-new

hand-me-downs like a gift, making lace

.

from landfill tampax, wearing away, in its rush

to cope, its damaged banks, wearing what face

but our own ? We are what it flows through.

The river is not an opportunity for narcissism, This is echoed in Price’s series of of full page river paintings They evade single, human-centred, perspective or focus of attention, creating a sense of mesmerising transition as one colour or form bleeds into another, changes direction, or shifts with the light. In some, there are drifts of phrases from the poems, like remnants of memory. The effect is of many simultaneous ingredients within a moving feast. We see artist dissolving the boundaries of the poet’s text, translating them into an image of the river’s way of knowing. And formally the poems also work against the boundary-making of their stanzas; lines fold and twist in riverly fashion, although always consonant with the shifts of thought. The language, too, shifts immaculately between registers, colliding the colloquial, philosophic, scientific, and glitteringly exact description, in a style unique to this poet. It allows Gross to superimpose beauty on murkiness much as the river itself. And after all, as the the poems remind, the Taff has a long memory that includes the grimness and upheaval of coal mining and the tragedy of Aberfan. Black is a constant under-presence in the paintings, literally leaving its mark in the charcoal and ink drawings that sometimes resemble both water-ways and coal seams. In the poem ‘A coal pebble’, a single washed up chip of coal has a near-incorporeality, a sense of being washed clean of the heavy past by its baptism in water. But just as the diminishing line lengths teeter towards a brink, so does the pebble image teeter over a catastrophic legacy:

greyish, with a slight glint at one angle, not quite

stone, but oval and wafery, light to the touch.

(Skimmed low, it could walk on the water

almost, right up to that panicky

teeter at the end.)

.

It comes clean as any other form the river, as if

innocent – bland, black and innocent – of what it did.

What it left. ( Not just under the hills

here but under the valley,

the deep navigation

Here, the past is tucked, or folded, inside brackets; folding, after all, is one unifying current of the book. It encompasses not only the folding together of artist and poet’s eye, and the curves of the river bank, but also, as noted in the title poem, A Fold in the River, the ancient Japanese art of orihon – a method whereby a book was pasted together to form a concertina. As both the poems and art explore, the river itself is concertina-like in its many coils and surprises, its back-flows and contrary intersections of past and present. It combines vertical depth to surface, origin to present manifestation, with linear flow. Ever paradoxical, it is distant one moment, present the next: ‘- suddenly loud, between narrowing sides/ of itself, then shut…’. (There is perhaps a nod here towards explorations of auditory experience one connects with Alice Oswald – that other great chronicler of rivers.)

Price and Gross render these paradoxes with a luminous physicality and a gaze that mutually concertinas ‘the many pages of the Taff’. After all, as Gross, suggests, water is merely a medium that takes its appearance from everything that has shaped it and from the shaping eye of the beholder. There there are rare moments when Gross’s sharp originality slips into more predictable analogies – ‘Taff/ as the water of life’ and his allusions to working class drug culture in the same poem feel tokenistic. But these are tiny blips in a virtuoso display of poetic intelligence allied to artistic. For this reviewer, A Fold in the River gloriously expands the beholding!